John Pfeiffer is an M.A. student in the Department of Russian & Slavic Studies at NYU. He specializes in International Relations with a focus on human rights, especially LGBT rights in Russia.

This fall, the International Print Center New York commemorates the centennial of the Russian Revolution with Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy (1917-2017). Curator Masha Chlenova combines historical, early-Soviet, and print media with contemporary works by Yevgeniy Fiks and Anton Ginzburg.

Upon entering the exhibit, the viewer will naturally gravitate toward Yevgeniy Fiks’s “Leniniana no.1.” Setting the tone for the entire show, this piece playfully recapitulates Aleksandr Gerasimov's (1881-1963) Socialist Realist “V.I. Lenin on the Tribune” (1930) — minus Lenin. Chlenova points out that because Gerasimov’s image was reproduced and re-printed ad nauseam in the Soviet state, it was easily recognizable to any Russian citizen. By removing Lenin from the podium, Fiks’s work invites the observer to reexamine the Revolution's cultural ambitions.

The exhibit, which features several historical Russian prints from between 1917 and 1930, illustrates the methods of dissemination and accessibility print media offered Soviet revolutionaries and their successors. Chlenova has centered the show on the revolutionary topics of racial equality, Jewish emancipation, shifting gender roles, and sexual liberation.

In one display, we see a collection of works featuring African-Americans in the Soviet Union. In 1922, Jamaican writer and poet Claude McKay (1889-1948) traveled to the Soviet Union to speak at the Fourth Congress of the Communist International. The following year, he recorded his impressions and experiences in the American civil rights journal The Crisis. His essay, entitled “Soviet Russia and the Negro,” recounts his perceptions of early-Soviet society as socially progressive, especially in contrast to the United States.

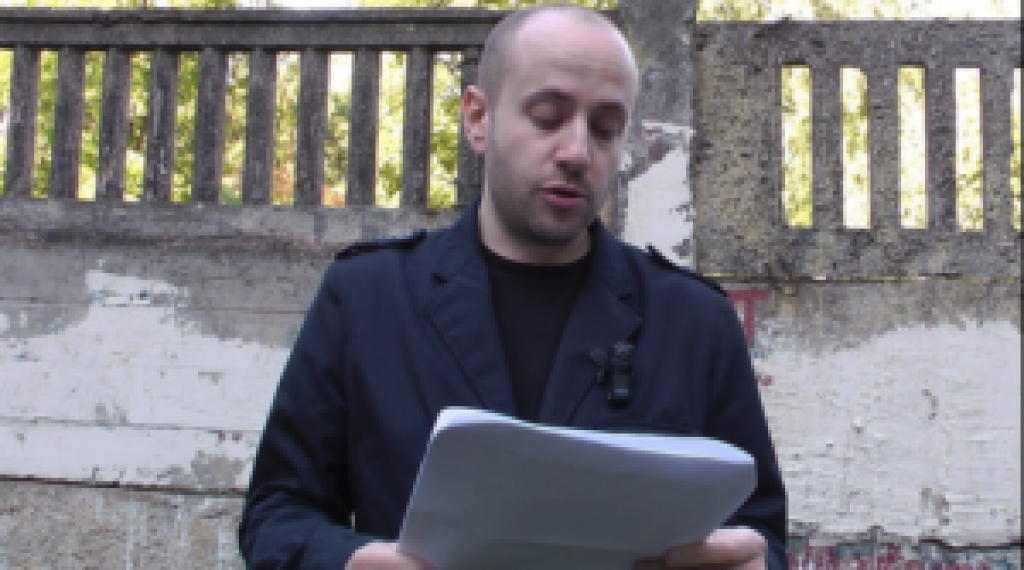

Opposite this display, visitors can watch footage of Fiks performing Russian-language readings of “Soviet Russia and the Negro” at sites of racially motivated crimes that took place throughout Moscow in 2011.

The exhibit also features copies of El Lissitsky’s “Had Gadya" (1922), a series of illustrations to the classic Passover song of the same name. These whimsical prints include the song's Yiddish lyrics as framing accents, yet retain a kinship with Lissitsky's characteristic avant-garde imagery. In a screen print that reinterprets Lissitysky’s famous “Beat the White with the Red Wedge" (1920), Fiks superimposes Yiddish translations over the original Russian words, thus invoking Lissitsky’s often forgotten Jewish heritage and gesturing at the historic Jewish struggle for social equality and emancipation.

One of Chlenova’s favorite images, Boris Klinch’s (1892-1946) “Working Woman: To Battle for Socialism, to Battle Against Religion" (1931), depicts an enlightened woman representing the ideal female product of the workers' revolution: technically educated, she looks out into the future utopia under Lenin's watchful gaze. In the shadows of the foreground, we see religious observance equated to domestic violence and misery. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, this idealized symbol of the Soviet woman has given way to far more sexualized images. Russian Orthodoxy is once again resurgent. Meanwhile, in February 2017, Vladimir Putin signed a decree decriminalizing some forms of domestic violence. These historical images serve as a reminder for just how far Russian society has regressed from the women’s liberation movements of the early Soviet Union.

Nearby, we see Anton Ginzburg’s “Revolution Was Ruined When It Rejected Free Love" (2016), in which these same words are overlaid onto a phallic symbol. Ginzburg's piece reminds modern audiences of the global struggle for gay rights and the limits of revolution as a vehicle for true sexual liberation — including both the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and Western "free love" movements of the 1960s and 1970s. By juxtaposing references to revolution with genital imagery, Ginzburg also conjures the persecution of the LGBT community in contemporary Russia.

By bringing together early-Soviet print media and modern works by Fiks and Ginzburg, the exhibit interrogates the extent to which the Bolshevik Revolution's goals were actualized in Soviet and post-Soviet society. History has shown that the road to social progress is long and non-linear. Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy captures a moment in Russian history when avant-garde art and political revolution mutually reinforced one another. Through their contemporary re-interpretations, Yevginiy Fiks and Anton Ginzburg re-evaluate, recall, and reimagine revolutionary ideals a century after their initial realization.

Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy is open to the public through December 16, 2017 at the International Print Center New York in Manhattan.