Natalie Ryabchikova is a PhD Candidate at the University of Pittsburgh and the Russian State University of Cinematography (VGIK)

Eisenstein in Guanajuato

The premiere of Peter Greenaway’s Eisenstein in Guanajuato at the Berlin International Film Festival on February 11, 2015 has been scheduled to coincide with the 67th anniversary since the famed Russian director’s death. A second biopic on Eisenstein’s journey abroad in 1929–32 is underway. In it, judging by his interviews, Greenaway is going to discard a couple of decades of film production in Switzerland to claim that Eisenstein made the first Swiss movie. The script has already caused some controversy between the British director and Russian film archivists, at least according to the Russian media, because of the “misrepresentation” of Eisenstein’s sexuality. Another hundred shorts are supposedly planned on all the famous people Eisenstein met in Europe and the US. Mickey Mouse and Rin Tin Tin have made the list, alongside Albert Eisenstein and James Joyce.

But I would like to step back from the debate, which, no doubt, now that Eisenstein in Guanajuato has premiered, will continue quietly simmering among of what is left of the European intelligentsia, and look instead at two other representations of Eisenstein that belong to the same period that Greenaway’s film covers, 1930–32. During this time, the Russian director, together with his co-writer and co-director Grigorii Aleksandrov, and his cameraman Eduard Tisse, traveled and worked in Europe, Hollywood, and Mexico. An early Greenaway—of such films as A Walk through H: The Reincarnations of an Ornithologist and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover—would, no doubt, have called this story The Highest Shave to be Received by Any Living Man.

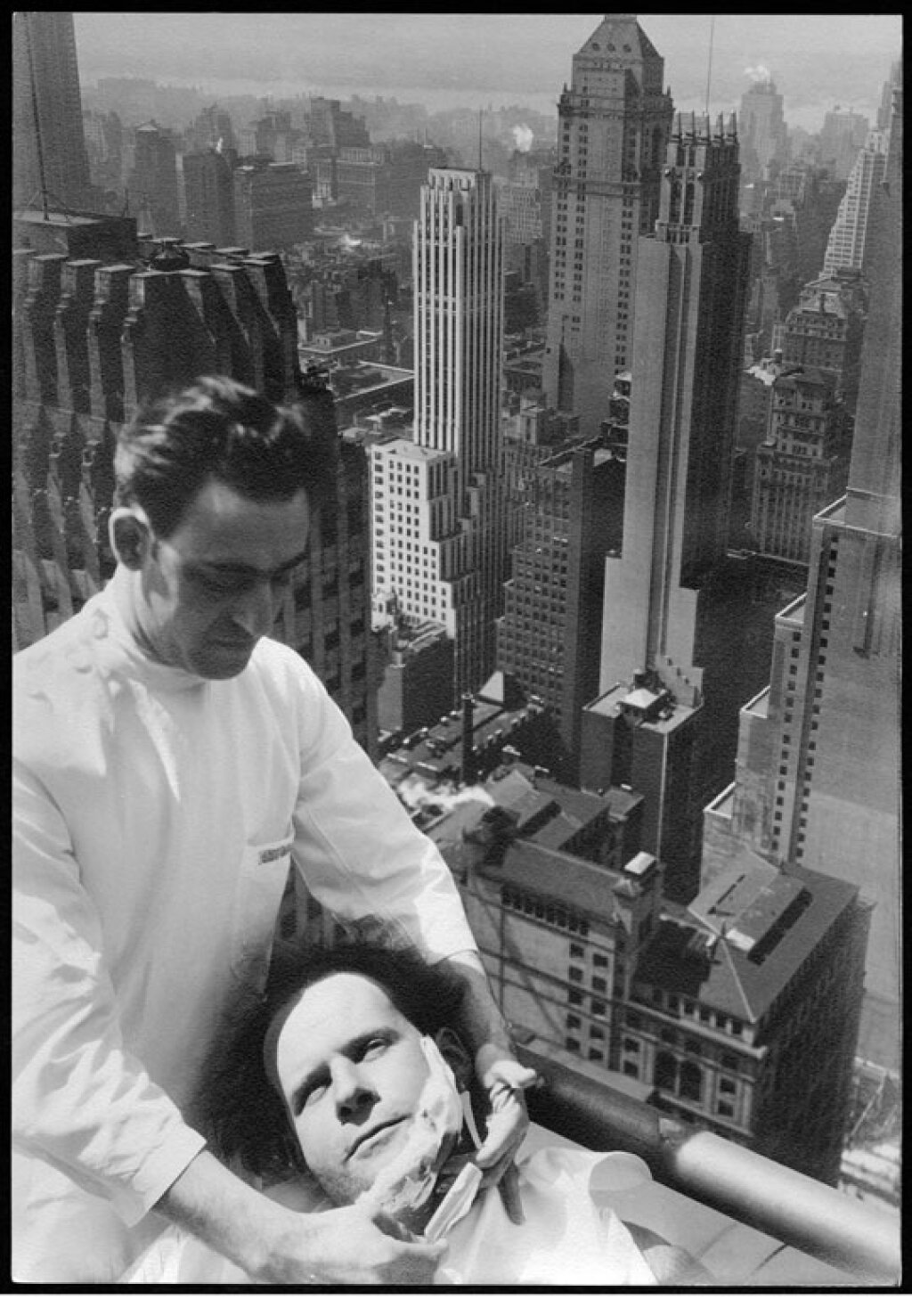

Yes, a shave. On top of the Chrysler building, which for the few short months of summer 1930 was the tallest building in the world, topping what was then The Bank of Manhattan and what is now known as The Trump Building by 6 stories, or 119 feet, or 36 meters. The man getting “the highest shave” in the world is Sergei Eisenstein; the woman taking pictures of it is the American photographer Margaret Bourke-White. The barber’s name is lost to history.

Two Photographs

Bourke-White opened her 61st floor Chrysler studio in 1930, the same year as the Building itself. She had been hired to document the progress of its construction, which was in competition with The Bank of Manhattan, and she had subsequently moved to New York from Cleveland, because she decided to have her new studio on top of the Chrysler tower. It was the highest studio in the world, she says in her memoirs, and for her the most beautiful: all glass, natural wood, and aluminium, with a sumptuous raspberry-coloured rug in the reception room. There was a tropical fish tank built into one of the walls. On the terrace, with its access to the two stained-steel gargoyles in the shape of the American eagles, overhanging the 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue, Bourke-White threw cocktail parties for her advertising clients. She rented the space because of the gargoyles, she said. On another, smaller terrace, she had an aluminium pond installed for her two pet alligators. For breakfast, she threw them slabs of raw meat.

Bourke-White wanted to go to Soviet Russia and, in the summer of 1930, was introduced to Sergei Eisenstein in the hope of getting introductory letters to important cultural figures there. Eisenstein had just arrived to New York a month before; he was taken with the skyscrapers, with Harlem night clubs, even with his room on the 18th floor of the Savoy-Plaza Hotel, overlooking Central Park. “I am head over heels in love with this city!,” he wrote to a childhood friend. He danced; he dined; he apparently shaved.

There are two known photographs by Bourke-White depicting this bizarre scene (one slightly more well-known than the other): a dark-haired man in a white smock standing over another man, sitting with his face lathered, his head leaning on a railing, behind which building after New York building rises in sharp geometric ornament of various shades of grey. One shot shows Eisenstein facing the camera, his head cradled in the barber’s arms; the other in profile, with one of Bourke-White’s beloved gargoyles in the background, obscured by the barber’s shoulder. The two photos seem to be taken with an interval of a few seconds, snap, snap. You can see her going around, hovering over the two men, higher than high. Apart from the angle, the difference between the shots is minimal: the barber’s hand is still poised over Eisenstein’s chin, his other hand delicately cupping his left cheek. The man standing frowns in concentration, the man sitting squints and almost smiles—you can see the sardonic rise of the corner of his mouth in profile. Perhaps he is also wondering what the hell it all means. The tallest building in the world, fine. The greatest film director in the world—debatable, but could be, and was successfully argued in 1930. But a shave? An old-fashioned shave, with a razor that in Russian they call “dangerous”; an uncannily private scene performed under an open sky, 800 feet over the sidewalks of the greatest city in the world.

A friend, with whom I shared my puzzlement, asked: “Was this perhaps done in preparation for a photo-shoot?” “No,” I immediately replied, “because no photo-shoot exists.” One could say, this was the photo-shoot, if the idea did not sound more preposterous than having pet alligators in a skyscraper penthouse. The prints do not have the straightforward smoothness of advertising photos, and, as far as I know, they were not utilized in any contemporary publications. But they are not accidental snapshots either. Eisenstein is deliberately positioned as close to the railing as possible, so that the Manhattan skyline is clearly visible behind him. The more well-known photograph is distinguished from the less well-known one by its slight tilt, its minimally higher angle, so that behind the men rises the brand new New York of art-deco skyscrapers: the 48–storied Chase Building (now known as 10 East 40th Street or the Mercantile Building), finished in 1929, with its brown stonework and a bright hipped roof; the Lefcourt Colonial Building just in front of it, completed a year later, with its 45 floors of yellowish concrete and bright blue mosaic rectangles at the very top; the startlingly white, minimalist by comparison, 43–storied Johns-Manville Building next to it; and right next to the Chrysler, the flag on the buttresses above the 56th floor of the Chanin Building built in 1929. Further behind, the smoke curls above the 41–storied wedding cake of the New Yorker Hotel and the white strip of Hudson forms the horizon. The slightly diagonal composition is dynamic, with the two brightly lit men in the left half of the picture balanced by the dark sharp-angled mass of buildings in the right. In the other photograph, another skyscraper almost grows out of the barber’s head, a Photography 101 no-no, which perhaps accounts for it being used less often. Still, this shot, where the razor’s edge gently touches the skin, features on the cover of a relatively recent book on Eisenstein’s theory of editing, which is known under the Russified French term montazh.

Cutting/Editing/Montage

Utilized as a cover for a book on montage, the photograph probably plays on the two meanings of the verb “to cut,” the polysemy of which is hardly less tired by now than that of “to shoot.” It sees shaving as a mundane yet inherently dangerous activity, the way flying could still be in 1930, and both fraught with psychoanalytical overtones, which Eisenstein himself appreciated even when he made fun of them. And yet, his montage was more concerned not with cutting but with suturing. He was obsessed with unity, with searching for larger connections between things that from a different, lower-level perspective might seem disconnected. His version of dialectics, starting with Hegel, encompassed almost anything from anthropology to nuclear physics.

For a long time I, too, looked at the two photographs the way others did: the top director, the top photographer, everything perfectly tip-top. “Sergei Mikhailovich must have been feeling on top of the world when Bourke-White snapped this picture,” as Bruce Posner put it in the 2001 booklet for the retrospective Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893–1941 at the Anthology Film Archive. In the summer of 1930 Eisenstein was opening a new page of his life, just off the boat to Manhattan in the whirlwind of press luncheons, university lectures (Columbia, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Chicago), and dinners with millionaires, on the way to Hollywood with a long fought-for six-month contract with Paramount under his belt, pending agreement on a story. And yet, there is something sinister in the barber’s lowered eyelids, the gaze directed at his hands, and something mistrustful in Eisenstein’s one open eye in the en face picture. The hand with the razor is hovering dangerously under Eisenstein’s chin, his mane of hair waving in the wind above the huge forehead that is growing bigger with every passing year. What he needs is a haircut.

The inventor of the safety razor, King Gillette, was still living in California in the summer of 1930 when Eisenstein arrived there. He asked to see the man, “whose name is known to more people on Earth than that of Vladimir Lenin.” He later remembered Gillette as a crazy millionaire with a penchant for building lush expensive villas in deserted places, each of which he would abandon in turn to go build a new one. “For many years,” Eisenstein continued, “I have lived in a similar way in relation to the events of my own life. Like a mule, a donkey or a horse, who has a piece of hay attached to his yoke in front of it, and so it keeps running after that hay wildly, hopelessly, eternally.”

Falling or Flying

This is not quite a story of artistic triumph. It is not a story of failure either. In Germany, France, Switzerland, England, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United States, Eisenstein was courted by movie producers and movie (and various other) celebrities, yet he had nothing concrete to show for himself for all these years abroad. No films, with which he could fully be credited, appeared; no new articles were published (except for translations); the theory book he had brought with him from Moscow grew into a very different book, but still remained only a heap of drafts. With each new country left behind and each opportunity that promised so much and delivered so little, Eisenstein told his friends: “It is all for the best. I have not compromised, and the next project is sure to be more successful than the last one.” The stakes were rising higher and higher. People he had known and worked with in Moscow started saying that Eisenstein’s “gallivanting” round the world would be his downfall: “Yes, he is high, but this is not flying, this is falling. And since he is so high, he can still take a long time falling…” The balance of his life and career abroad was precarious, and he hurried headlong so as not to hesitate a second too long and fall down.

Bourke-White, who in the winter of 1929-30 had to work on the unfinished Chrysler tower as it swayed in the subfreezing wind, said she learnt something from its welders and riveters: “…when you are working at 800 feet above the ground, make believe that you are 8 feet up and relax, take it easy. The problems are really exactly the same.” Perhaps, then, getting a shave on a 61st floor terrace with two pet alligators at your side is really no different than doing it 60 floors below.

And yet, the razor’s sharp edge is at Eisenstein’s throat, and behind the barber’s gleaming white shoulders rises a hazy silhouette of Empire State Building—still non-existent in the early summer of 1930, but completed and topping the Chrysler Building’s height by about two hundred feet by April 1932 when Bourke-White and Eisenstein met again. While Eisenstein had travelled westward, exploring Hollywood and then Mexico, Bourke-White had gone East as she had hoped to, bringing her camera and her eye for industrial photography to the hectic construction sites of the First Soviet Five-Year Plan. Russia was developing in width at the time, while Manhattan was growing in height. Stopping in New York on his way back to Moscow, Eisenstein had time to meet with Bourke-White again and to receive her new book Eyes on Russia with the inscription: “To Sergei Eisenstein, the only man to be shaved in my studio, 800 feet above the sidewalk—the highest shave to be received by any living man.” This was 7 April 1932, and this, or shortly before that, is when the shaving and the photo-shooting occurred.

That is a very different story from the one that can be told about 1930. Not at all straightforward; perhaps not a story at all. The agreement with Paramount was dissolved in November 1930 after several scripts, suggested by Eisenstein, were rejected. He then went to Mexico, hoping to make a travel film financed by writer and Socialist Upton Sinclair and his wife and acquaintances. Instead of the projected couple of months Eisenstein stayed in Mexico for more than a year, filming about 33 miles of footage—more than 30 times the height of the Chrysler Building,—and yet having to leave before the last portion of the material, as he envisioned it, was shot.

Eisenstein just spent a humiliating and boring month on the Mexican-American border waiting to be allowed back into the country after Upton Sinclair had cut financing of their Mexican picture that, by Eisenstein’s estimate, he only needed a month to finish. Back in the Soviet Union, the Politburo decided to pronounce him a defector, of which Joseph Stalin’s telegram had informed Sinclair. And yet, in Eisenstein’s suitcase as he left New York there was a telegram from Sinclair promising to send the Mexican materials with the next boat for him to edit it in Moscow. He was able to show some of the Mexican footage to New York acquaintances. He was still hopeful.

And yet, on the border at Nuevo Laredo, while waiting for the transit US visa, he met pilot Jimmy Collins, a classmate of Lindberg, who had taken Eisenstein and his friends on a flight above Manhattan one spring night in 1930, when hundreds of thousands windows started lighting up, making the houses look like stacked black dominos with illuminated twos, threes, sixes, and fives. Later Eisenstein described Collins as an admirer of Spengler’s Decline of the West, a disenchanted intellectual and inventor who had to work as an air taxi driver going from Mexico to Hong Kong to Bombay on his employer’s whim and who then became a test pilot, always unsure of his future, always haunted by a ghost of his potential death in the interests of some aviation enterprise shareholders, which was exactly what happened in 1935. Collins, Eisenstein said, had predicted and described his death in the book Test Pilot, shortly afterwards adapted as a vehicle for Clark Gable. Eisenstein never quite trusted the view from the top, even in his most optimistic moments. As poet Arseny Tarkovsky, the father of that other most famous Russian filmmaker, Andrey Tarkovsky, wrote in the 1960s, when Soviet men started buying electric shavers, “…and all the while fate was hard on our heels like a madman with a razor in hand.”

Occam’s Razor

Herein lies my problem with Greenaway’s projects. No other director in the world is more steeped in myth than Eisenstein. He was his own first and best mythologizer. He also seems to never have thrown a piece of paper away, firmly believing that the surest way to hide something is to tell everything. I do not know who did research for Greenaway and for how long; I have not seen the film. All I know for sure is that Greenaway insists his film is based on historical research and that it is named Eisenstein in Guanajuato. I also know that I have not encountered any mention of the Mexican town of Guanajuato during the several months and years I spent in various Moscow and US archives related to Eisenstein; I have not seen it in any of Eisenstein’s published and unpublished memoirs, diaries, letters, maps, and booklets; in any of the books written by people who did more research than I have done. This seems to be such a trivial matter—one word, one town, one love affair, and a story revolving around it. And Eisenstein is such a well-established figure; he is part of the international film history canon; his films or writings are taught in at least every second film course in the country—what harm can a biopic do? Moreover, this is not the first time film audiences are presented with a screen version of Eisenstein. Just two weeks ago Russian film director Aleksei Fedorchenko, who had become famous with his 2004 mockumentary about the Soviet lunar mission anticipating Apollo 11, presented his new film Angels of Revolution at the New York Jewish Film Festival. Fedorchenko rather alluded to than presented Eisenstein on the screen, and yet after the film’s European premiere last fall one well-known young Russian film critic remarked on Facebook that now that he knew Eisenstein had killed three men in Mexico (or should I say, “shot during shooting”?), it really changed his perception of Eisenstein and his art.

Is it tempting to think that one has once and for all explained Eisenstein for oneself; tempting to grasp at a fiction that seems so vivid and to believe that Eisenstein is a quantity so well-known only a Fedorchenko or a Greenaway could make him fun again. Meanwhile, Eisenstein’s profile on the Internet Movie Database has for a while now featured as the primary photograph not his portrait at all, but that of his collaborator Aleksandrov. That picture probably explains a lot to some people too.

I am not bothered by what they call “artistic” truth. God knows, Eisenstein practically made a name for himself with it; his staged scenes of the revolutionary storming of the Winter Palace, for instance, have been repeatedly (mis-)used as documentary footage from October 1917. I am bothered by the pretense of artistic truth to be historical, because then even people who should know better find it easy to believe in it. As a historian, who used to make her living reviewing films, I also take issue with the opinion that facts are boring unless they are embellished by fantasy. I believe that half-truth is more harmful than outright invention and that history is still infinitely more fascinating than historical fiction—if we bother to look into it closely enough. History is messy and mysterious, and her sister biography even more so. It likes to defy the scientific principle that posits that the explanation with fewer assumptions is better than the one with more. This principle is commonly known as Occam’s razor. And William of Occam surely did not mean the safety one.