The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Hannah Gadbois is a second-year doctoral student at the University of Illinois, Chicago specializing in the Soviet avant-garde.

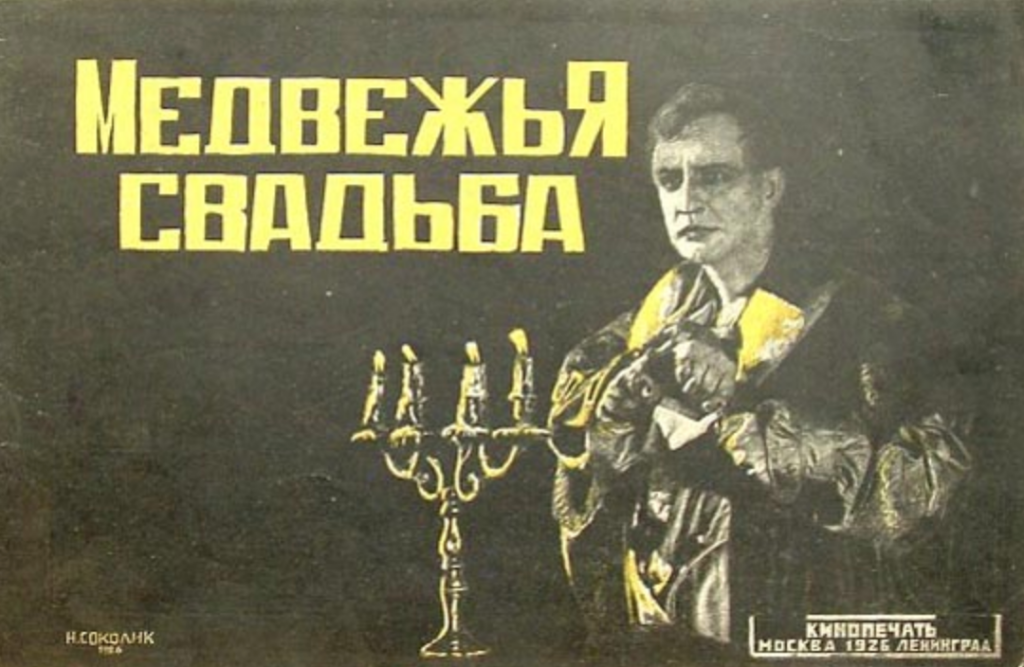

“In front of The Bear’s Wedding poster, a NEPachka shines in the glow:

‘I’d like to sleep with a bear like that! Bite me, darling Eggert.”

The 1926 Soviet melodramatic horror film The Bear's Wedding (dir. Vladimir Gardin and Konstantin Eggert) has long been considered an ideological flop despite its commercial success. When first released, the film, based on French author Prosper Mérimée’s novella Lokis (1869), met virulent accusations of ideological uselessness that aligned it with pre-revolutionary escapist films. Critics further maligned it for its overblown budget (it was financed by the German-Russian production studio Mezhrabpom). The film’s reputation did not improve with time. Soviet film-historical scholarship focused on its popular success as a sign of the low standards of "the masses," who were said to prefer entertainment to culturally revolutionary cinema.

This post takes The Bear's Wedding seriously as a portrayal of the monstrous. As the sole example of early Soviet supernatural horror (or perhaps even horror as such), the film offers insight into the shape of the dreadful in the early Soviet Union—a horror that obviously resonated with audiences, given the popular success of the film.

The film opens on a hunting expedition held by the elder Count Shemet, during which the pregnant Countess is attacked by a bear. The terror of the event drives her mad, leading her to believe that her unborn baby is a bear. Thirty years later, the younger Count Shemet is shown as a sentimental young man who keeps to himself in his gothic castle. From time to time, he enters a fugue state, transforms into a bear, and chases women through the woods. Shemet marries a young woman named Yulka, but awakens after their wedding night to find her slain. When the townspeople learn of his crime, they form a mob and run Shemet through the woods. Jan Bredis, a doctor, finds and attacks him back at his castle. In their fight, Yulka’s sister Pana Maria happens upon a gun and shoots Shemet, even as he overpowers Bredis.

With a screenplay by Anatoly Lunacharksy, the head of Narkompros (the People’s Commissariat for Education) from 1917 to 1929, The Bear’s Wedding was enmeshed in the politics of the time. Unlike the majority of Narkompros members, Lunacharsky advocated for entertainment and free creative rein in cinema over propagandistic government control. At the same time, he distinguished between this ideal entertaining cinema and “abominable commercial cinema,” arguing that “a consciously propagandizing cinema that wants to teach is like someone with their legs in irons.” Lunacharsky believed in striking a middle ground between plainly political cinema and bourgeois commercial cinema.

Lunacharsky’s conception of melodrama understood it as a marriage between popular entertainment and emotionally stirring, clear messaging. For Lunacharsky, melodrama was the best form of exciting agitation because of its penchant for high drama, clear plot lines, strong emotions, and poetic quality. The Bear’s Wedding readily embodies these characteristics of melodrama, with the romantic figure of the count, the gothic castle, and the power of love occupying the center of the narrative. Lunacharsky set out to rehabilitate the estimation of popular taste as "lowbrow." “Much ink has been wasted exposing, with an admixture of haughty sneering and fiery indignation, all the vulgarity of so-called success with the crowd," he wrote. "As democrats, we ought to reassess this hierarchy of value.” The critical dismissal of The Bear’s Wedding, a seminal melodrama, threatens to reinforce the traditional "hierarchy of value" that throws popular taste to the wolves. Lunacharsky thought that film, and especially melodrama, are able to "call forth the undivided and total emotional reactions of compassion and indignation.”

Yet in The Bear's Wedding, it is difficult to relate to any single figure. The most likely vessel for audience empathy is Yulka, Count Shemet’s young bride. Although her death is sad, she is a rather shallow character, concerned almost exclusively with dancing and flirting. Furthermore, Yulka’s death at the end of the film is the natural end to a melodrama. As Beth Holmgren argues, the heroine of the Russian melodrama almost always dies. In place of life, she is rewarded with a charismatic power, playing a positive and effective role that is almost religious in its moral potential. Though venerated, the heroine thus remains a relatively simple character. But is she the optimal recipient of audience empathy? How far can one be moved in defense of a figure destined for death and subsequent glorification?

Early Soviet audiences—as the quote that opens this essay reflects—related to the character that embodied not virtue, but monstrosity: the younger Count Shemet. Throughout the film, this character struggles to determine whether he can safely marry Yulka, to whom he is clearly devoted (Figure 1). Shemet even considers canceling the wedding and giving up his estate so as to protect Yulka from himself. Meanwhile, the man who encourages him to cancel the wedding, Jan Bredis, is a sneaky, plotting figure who snarls from under a furrowed brow, evidently conspiring to take up Shemet’s power and romance (Figure 2).

Compare, for example, the faces of Shemet and Bredis directly before they fight—because Shemet believes Bredis is attempting to take his bride and home. Whereas Shemet’s eyes express betrayal, his forehead wrinkled with concern (Figure 3), Bredis’s face (Figure 4) flashes up onscreen for only a moment as a picture of pure rage. The screen time contributes to this sense of Bredis as unpredictable and frightening. His face is difficult to gaze at, popping up only for instants, while Shemet’s dominates the screen in long, emotional reflection.

Indeed, the horror of The Bear’s Wedding is not embodied by Shemet himself, but instead lives in Shemet’s struggle with his cursed inheritance, his propensity to transform into a bear. In killing the evil that lived within him, the village people dispensed with the danger he presented. However, this cleansing came at a great cost: the life of the film's real hero. The possibility of reveling in his death is lost in the moment of Yulka’s. We do not see Shemet’s attack, only his horrified face upon awakening and finding her dead (Figure 5). He stands aghast, pulling aside the blanket that covers her dead body before dropping it to the floor and raising his guilty hands. The horror lies not solely in her death, but in the pain he experiences as a result.

[gallery type="slideshow" columns="5" size="medium" ids="8154,8153,8152,8151,8150"]

In the end, The Bear's Wedding suggests that the truly cursed are those without agency, those doomed to suffer through circumstances beyond their control. Claims of ideological uselessness could hang on these ambiguities: the death of the aristocrat feels tacked-on, or, what is worse, potentially encourages the viewer to mourn and romanticize him. At the same time, though the film seems to push viewers toward pity for an aristocrat, it stops short of presenting him as an object of envy. In a communist society, wouldn't the real horror lie in the idea of a fate determined by accidents of birth, of class, and of heritage? And isn't there beauty and compassion in mourning those without the agency to find, and keep, love?