This is Part I in a two-part series. Part II will follow on Wednesday, 10/14.

Ekaterina Olson Shipyatsky and Fiona Bell worked as 2019-2020 Fulbright English Teaching Assistants in Ulyanovsk, Russia.

Ekaterina Olson Shipyatsky graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 2019 with a degree in Philosophy, Politics, Economics (PPE). In 2020, she worked as a volunteer translator and researcher for the GuLAG Museum and the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow. She plans to pursue graduate work in the fields of genocide studies, political theory, and interdisciplinary human rights.

Fiona Bell is a literary translator and scholar of Russian literature. Her writing has appeared in Full Stop, Asymptote Journal, The LA Review of Books, and elsewhere. She is from St. Petersburg, Florida, but currently lives in New Haven, Connecticut, where she is earning a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University.

There’s nowhere better than Goncharov Street, at least in Ulyanovsk. Before the spread of COVID required us to leave our English teaching posts in Lenin’s hometown, we’d become regulars at the street’s Café Dalí: the hotspot for 10AM backgammon games between middle-aged men and fashionable couples’ photoshoots. In fact, the cafe offered the perfect backdrop for millennial photoshoots: plants, a chalkboard menu, and strategically-placed books. It took us a few months to notice that, in between the collected works of Goncharov, Lermontov, Pushkin, et al., stood Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs.

American tech leaders crept into our Ulyanovsk lives more and more with each passing day. In one of our English classes, a couple of eighteen-year-old guys — the only students who had been to the U.S., and some of the few who had been abroad — gushed about Elon Musk’s podcast appearances. Another student gave a passionate speech on why Mackenzie Scott (formerly Bezos) was a "gold digger." In the afternoons, we started meeting up with a young doctor who was working on a medical start-up in his spare time. He told us that Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead was his favorite book because he identified with the characters, though when he recommended it to his friends, they said that none of the protagonists seemed human. We also talked about American tech giants like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, and he told us about his dream of eventually moving his start-up to Silicon Valley.

In a time when thinkpieces on Silicon Valley’s pernicious blend of late-stage capitalist hijinks and Allbirds™ are never far from either of our Facebook feeds, we were disturbed by the widespread interest in these putative tech gods, interest we encountered everywhere from our universities to our favorite café. Before moving to Russia, we had learned to be wary of Silicon Valley’s amoral insistence on technological progress as an inherent good.

We wondered whether our misalignment on this issue with our host city was a matter of cultural and economic difference. Silicon Valley, separated from Ulyanovsk by complicated visa restrictions and an ocean, was a short plane ride away from both of our hometowns. Maybe these “tech giants” didn’t appeal to us for the same reason that our Ulyanovsk peers had tired of Lenin: proximity kills curiosity.

And yet, we also had American peers who related to tech leaders with starry-eyed reverence. These “tech geniuses,” we realized, are the heroes of our — around the entire globalized world — precisely because people perceive their meritocratic life narratives as the antidote to income inequality, the fundamental conflict of our time.

***

Around Halloween, one of us — the one with a penchant for Twin Peaks — came up with a new English class icebreaker: “If you had to be haunted by someone, who would it be and why?” We posed the question to our classes at different universities, and students responded with the usual pop culture suspects: Freddy Mercury, Einstein, and Michael Jackson. However, we were surprised at some of the other figures who came up consistently among both our groups: Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, Stalin and Hitler. When we asked our students why they wanted to be haunted by these four men, the reasons they gave were always the same: good leadership, effective management, the ability to inspire large groups of people, and the hope that, as their corporeal hosts, they might be on the receiving end of the ghosts’ “brilliant” ideas.

In the months that followed, we started wondering whether we’d been wrong to brush off some of our Russian students as international versions of the American tech bro. Even if this stereotypical figure was a global phenomenon, it had certainly taken on a distinctly Russian character in our students’ imaginations — indeed, Hitler and Stalin are key figures not just in world history, but in Russian history. We considered whether our students’ attitudes towards mythologized dictators informed their interactions with American tech leaders. So we began to think about hero-worship throughout Russian history: how does the Airpod-sporting, Tesla-obsessed Ulyanovsk teen compare to Eugene Onegin with a bust of Napoleon in his study? (Full Details: StockApps guide on buying Tesla shares)

These sorts of comparisons, especially when they involve historical perpetrators of atrocities, are dangerous. Rather than making sweeping judgments about our Russian peers and the people they respect, we wanted to understand the distinct contexts that inspired their idolization of these figures. After all, chances are, we are also subject to similar influences.

In our view, the impulse to worship is perennial, and the shape of hero worship across Russian history is strikingly consistent in many cases. However, another equally dependable truth is this: for every hero, there is a host of critics and clowns injecting bathos into the hero narrative. And, just as with Napoleon, Hitler, and Stalin, the ways we worship or lampoon Silicon Valley leaders reveals something about our own moral positioning.

***

It’s impossible to talk about the worship of morally complicated figures in Russian history without thinking about Napoleon.

Apart from his morally questionable approach to both war and domestic politics, Napoleon was the Russian Empire’s most formidable enemy for the early years of the nineteenth century. During the 1812 invasion, many Russians perceived the leader as the Antichrist, comparing him to the Tatar invaders in the fourteenth century and connecting him with scripture from Revelations. Others welcomed him as the Messiah, a liberator who might save them from Russian autocracy and even serfdom. By the 1820s, Napoleon’s meteoric trajectory lent itself to both the romantic and liberal mythologies then developing in Russia.

Just as peasants saw in Napoleon a liberalism that didn’t exist, today’s worshippers of American tech leaders look to Silicon Valley "innovation" for answers to serious issues like income inequality and climate change, even when tech companies prove time and time again that they are driven solely by profit. Like Napoleon, too, these leaders are often figured in religious terms: memes floating around the Russian internet portray Elon Musk’s likeness in Orthodox icons. A cursory look at Russian-language writings on Steve Jobs yields many comparisons of Steve Jobs’ rescue of Apple Corporation during the 2008 recession to Jesus’ rescue of humanity from sin.

In her book on Napoleon in Russian culture, Molly Wesling argues that Napoleon was a central figure in the nineteenth-century Russian national imagination: it was against him that the emerging nation defined itself, both in literature and public life. Perhaps the valorization of tech CEOs is part of an attempt to renegotiate Russian identity in the twenty-first century. It seems that the romantic-era appreciation of Napoleon in Russia foreshadowed attitudes towards some of the country’s current cultural “invaders”: Elon Musk and Steve Jobs.

Before Apple and Tesla captivated the world, Hitler’s 1941 invasion of Russia unleashed horrors never-before-seen on Soviet territory. It was surprising, then, to hear our students mention Hitler in response to our Halloween haunting question. Students said that they would choose to be haunted by Hitler in hopes that he could help them to “motivate people toward a common goal” or “convince everyone to do what he wanted.” We were disturbed to hear this amoral assessment of Hitler’s “virtues.” The students seemed to dissociate Hitler’s abstract leadership skills and the horrifying ends to which he used them. What’s more, the students ignored the possibility that Hitler was considered motivational only by people who already agreed with the racist ideology he was promoting. Whether this appreciation for Hitler reveals the students’ sympathy for Nazi ideology, unconditional respect for managerial skill, or historical illiteracy is unclear.

But Hitler isn’t the only twentieth-century dictator who has been recast as a “good manager,” even by our students; the contemporary resurgence of Stalin’s popularity is by now well documented. Fewer connections, however, have been made between this nostalgic trend and Russia’s newer interest in Silicon Valley leaders.

A few months after the icebreaker incident, we took a trip to Moscow. One night, as we dug into some cheesy khachapuri at a Georgian restaurant, we looked up and saw Stalin’s face staring at us from behind a plant — and from inside the Google logo? We took a closer look at the photo’s caption: “Stalin is like Google: Give him a word, he’ll give you a link/prison time” (“Сталин - он как Google: ты ему слово — он тебе ссылку”). The Russian pun plays on the homonym “ссылка,” which means both “link” and “hard labor.” A homonym linked Stalin and Google on a linguistic level, while the theme of surveillance linked them conceptually. Was this comparison meant to flatter the dictator or to indict both him and the tech company? Why was this meme hanging in a Georgian restaurant on Tverskaya? Had we cursed ourselves to be haunted forever by our students’ Halloween icebreaker responses?

Stalin interrupting our meal from behind an indoor rubber plant was the final straw, so we decided to do some more research. We found a 2015 Meduza piece that documents the opening of Penza’s “Stalin Center,” whose director believes that “We need Stalin, Steve Jobs, and Elon Musk. But without repression” (“Нам нужны Сталин, Стив Джобс и Илон Маск. Только без репрессий”). According to him, contemporary Russia can seek its own “hero-innovator” (“герой-инноватор”) and “man of the future” (“человек будущего”), while leaving aside the ugly repressions of Stalin’s regime.

Where the director of Penza’s Stalin Center saw in Stalin a Napoleonic greatness, others admire the leader’s everyday, "managerial" prowess. One business article compares Steve Jobs’s leadership style to Stalin’s. Apparently, both Jobs and Stalin “instituted strict standards, rules, and chains of command,” “set up continuous evaluation criteria which allowed them to narrow in on goals,” and “accurately followed a premeditated plan, which allowed them to avoid time-consuming errors” (“Установление четких стандартов, правил и критериев производительности, соблюдение строгой субординации,” “Постоянная оценка критериев, сроков, ролей, обязанностей и определение вспомогательных целей, которые позволяют приблизить главную цель,” “Точное следования намеченному плану, что позволяет избегать ошибок, устранение которых требует времени.”)

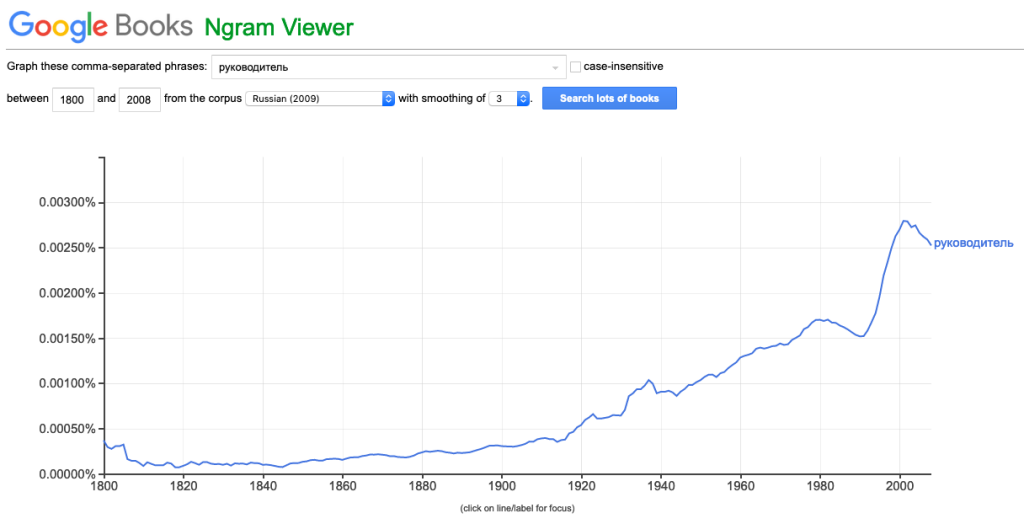

Both Stalin and Jobs’ leadership skills recur in the article's abstract: effective planning and efficient management are virtues because they enable a monomaniacal focus on goals. The goals themselves are apparently irrelevant in the assessment of the two men’s leadership styles. This entanglement of Stalin nostalgia and tech hero-worship is apparent even on a linguistic level. The above business article introduces Stalin as the “manager” (“руководитель”) of the USSR, a title usually reserved for private sector figures. Other online articles refer to him as an “effective manager” (“эффективный менеджер”). Both of these titles imply a twenty-first-century, capitalist setting. In fact, a Google (!) Ngram search reveals that instances of “руководитель” in the Russian corpus shoot up in the 1990s, correlating with the rise of Russia’s private sector.