This is Part I of a three-part series. Part II may be found here and Part III may be found here. A version of this piece originally appeared on Gorky Media.

Ilya Vinitsky is Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Princeton University. His fields of expertise are Russian Romanticism and Realism, the history of emotions, and nineteenth- century intellectual and spiritual history.

Translated by Emily Wang, Assistant Professor in the Department of German and Russian Languages and Literatures at the University of Notre Dame.

1.

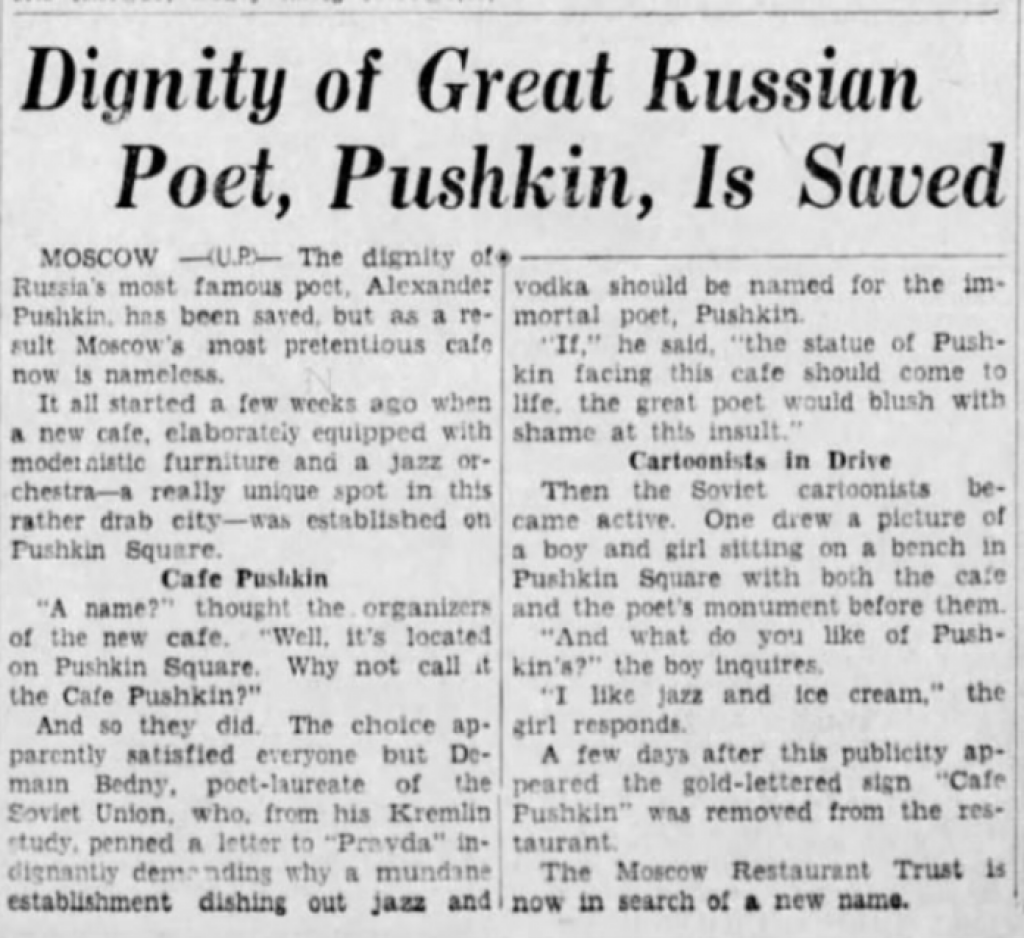

In November 1934, one year after the Soviet Union was officially recognized by the United States and some months following the First Congress of Soviet Writers, where Socialist Realism was first declared to be official doctrine, several American newspapers printed a letter from the United Press correspondent Joseph H. Baird. This letter concerned a certain scandal that had taken place in Moscow in October. Baird’s text was published under various headlines (“Moscow Letter,” “Cartoonists Poke Fun at Poet, So Restaurant Loses Its Name,” “Dignity of Great Russian Poet, Pushkin, Is Saved”), but in all publications its contents remain unchanged:

The dignity of Russia’s most famous poet, Alexander Pushkin, has been saved, but as a result Moscow’s most pretentious café is now nameless. It all started a few weeks ago when a new café, elaborately equipped with modernistic furniture and a jazz orchestra – a really unique spot in this rather drab city – was established on Pushkin Square.

Café Pushkin

“A name?” thought the organizers of the new café. “Well, it’s located on Pushkin Square. Why not call it Café Pushkin?” And so they did. The choice apparently satisfied everyone but Demyan Bedny, poet laureate of the Soviet Union, who from his Kremlin study penned a letter to “Pravda,” indignantly demanding why a mundane establishment dishing out jazz and vodka should be named for the immortal poet, Pushkin. “If,” he said, “the statue of Pushkin facing this café should come to life, the great poet would blush with shame at the insult.”

Cartoonists in Drive

Then the Soviet cartoonists became active. One drew a picture of a boy and a girl sitting on a bench in Pushkin Square with both the café and the poet’s monument before them. “And what do you like of Pushkin’s?” the boy inquires. “I like the jazz and ice cream,” the girl responds.

A few days after this publicity appeared the gold lettered sign “Café Pushkin” was removed from the restaurant.

The Moscow Restaurant Trust is now in search of a new name. (Green-Bay Press Gazette, November 19th 1934, p. 15)

Baird’s feuilleton was no canard or fantasy on the theme of Soviet Russia, of which there were plenty in the American press during this period. It was inspired by a real incident, one that a person familiar with Moscow’s ideological cookery like the United Press correspondent felt deserved attention. Students of Soviet socio-cultural history in the mid-nineteen-thirties might also find the topic to be of interest.

2.

The fashionable Pushkin Café, located at the intersection of Gorky Street and Pushkin Square, really did exist. According to Yury Fedosyuk, author of the book Moscow in the Garden Ring, it stood among buildings that had been rebuilt in 1934 and now housed the Working Moscow publishing house, as well as the Teakinopechat printing union. By all appearances, the café's opening was timed to correspond with the First Congress of Soviet Writers. One attendee, the German writer Oskar Maria Graf, detailed his visit to the “lovely and unexpectedly tasty” establishment in his memoir, Traveling Through the Soviet Union in 1934. The restaurant director, who had himself come to the USSR from Dusseldorf, told Graf that despite Soviet bureaucracy and the difficulties of a planned economy, he was planning to open several more cafés catering to the tastes of the Soviet public: “As soon as everything gets sorted out, this will be a paradise,” he averred. And indeed, in 1934 Moscow saw the opening of several more “model,” professional cafés, including one for journalists in the House of the Press [Dom pechati]” (to which we’ll return in a moment).

The newspaper Evening Moscow [Vecherniaia Moskva] informed its readers about “Café Pushkin” in a brief note entitled “The Model Café Pushkin”:

Today at 6 PM a new model café will open on Pushkin Square. It has been given the name of A. S. Pushkin. The new café will have three rooms. The walls have been upholstered with a special material produced on special order by the Orekhovo-Zuevo textile factory. In the main room an orchestra will play, in the second – a round hall -- will have a space assigned for dances. The third room is meant for relaxing. Here you’ll be able to get cash, newspapers, and magazines. The café will be open from 8:30 in the morning until 1:30 at night.

This note caught the eye of Maksim Gorky — the most important Soviet writer and, since August 27, 1934, the chairman of the All-Union Pushkin Committee within the Central Executive Committee of the USSR, a body tasked with organizing events to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the great poet’s death. Gorky wrote an angry (and somewhat incoherent) letter to First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party, L. M. Kaganovich, to which he had attached the clipping from Evening Moscow:

Dear Lazar Moiseevich! I must disturb you once more. Allow me to direct your attention to this clipping from Evening Moscow, attached below. A café-restaurant named for A. S. Pushkin is an inadmissible stunt representing the compromise of Soviet power. As a citizen of a country that is in the process of creating its culture anew, where the literary person’s labor [is supported by] the government and the proletarian masses, and as a literary person and Chairman of a Committee for honoring the centenary of the great poet's untimely death — a poet driven to the grave by [what he called the] “fashionable mob” — I must protest against the form of commemoration expressed in the creation of this café. I implore you to change this café's “royal title.” I assure you that this fact will constitute a motive for our enemies to attack us and that this time they will attack us justifiably. With heartfelt regards, &c.

Gorky understood the assignment of Pushkin’s name to this café as a new attack by the “fashionable mob” (it seems that he has in mind the NEP-era – or NEP-corrupted – elite) directed against the great national poet (here, it seems, the Pushkinian antithesis of the “poet” and “mob” is being used politically), as well as a wholesale compromise of the same Soviet power that professed to value Pushkin so much. There is no doubt that Gorky associated what he saw as an inappropriate and offensive use of Pushkin’s name with the tastelessness of the “bourgeois” pre-revolutionary jubilee events of 1880 and 1899, when Pushkin’s name had “sanctified” special “commemorative” editions of vodka, tobacco, a national cannon, cigarette, matches, boots, and so on.

Gorky seemingly took the name of the café on Pushkin Square as a direct and malicious (as well as petty-bourgeois) attack on the concept and task of the newly-founded Commission “for the immortalization of great poet’s memory and the wide popularization of his creations among the workers.” Moreover, according to the Soviet author, such a “title” for a café would enable spiteful laughter on the part of the USSR's enemies. In other words, the opening of a Pushkin Café was no localized Moscow incident, but a subversive action fraught with international consequences. (Indeed, Baird’s mocking letter, published in the American press, confirmed Gorky’s concern.)

Finally, Gorky’s ire also has a spatio-symbolic explanation. The opening of a café named after Pushkin featuring “bourgeois” dishes, dances, and, it seems, jazz, which the pages of the “vulgar” Evening Moscow constantly advertised, located on the corner of one of Moscow’s main thoroughfares (itself named in honor of the chief writer of the new era) and the city’s central cultural square, which boasted its main literary monument at its center – all this, to Gorky, represented such aesthetic blasphemy that it demanded the interference of the party press and city authorities.

Kaganovich replied to Gorky on October 29:

The Moscow Committee has accepted your first, entirely correct, proposal regarding the withdrawal of the name of Café Pushkin. It has also disciplined those responsible. Unfortunately, this suggestion was presented to the Moscow Public Feeding Trust [Mosnarpit] by Mikhail Kol’tsov, as it turns out, from whom the Moscow Committee has demanded an explanation. A policy has now been instituted according to which enterprises may acquire this name only with the permission of the Moscow municipal administration [Mossovet].

Kaganovich's letter reveals that the man who initiated Pushkin Café's founding was none other than celebrity journalist Mikhail Kol'tsov, then-editor of the illustrated weekly Little Flame [Ogoniok] and future editor of the famous satirical magazine The Crocodile [Krokodil] — who, like Gorky, also happened to be a member of the Committee for the Commemoration of Pushkin. This incident had two indirect administrative and bureaucratic results: first, as Kaganovich notes, the name was withdrawn. Second, Mosnarpit lost the right to name culinary establishments according to its own whims. This act now became the prerogative of the Party’s Moscow Committee, specifically Comrade Kaganovich himself. The Party’s power over naming (and renaming) all objects of Soviet life (let’s call it “Party-Soviet Adamism”) became even stronger.