Natasha Kadlec studies Russian literature at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Now I’ll tell you about how I was born,” wrote the poet Daniil Kharms in 1935: “I was born twice….” Kharms goes on to detail the process by which his father, wishing for his son to be born on New Year's Day, forcibly reversed the author’s premature birth. By this logic, Kharms was born twice: once four months early, and once — indeed — on January 1.

Writing like Kharms' was hardly consonant with the dominant currents of official Soviet literature under Stalin, but since his posthumous circulation in samizdat during the 1960s, Kharms has become a cult icon of alternative culture. In the years leading up to Soviet collapse, he even became a legitimate, if marginal, object of academic study. More recently, his lyrics have been set to music – from Ukrainian band Esthetic Education’s Juravli i korabli (2006) to Icelandic composer Hafliði Hallgrímsson’s What They Sell In The Stores Nowadays (2009).

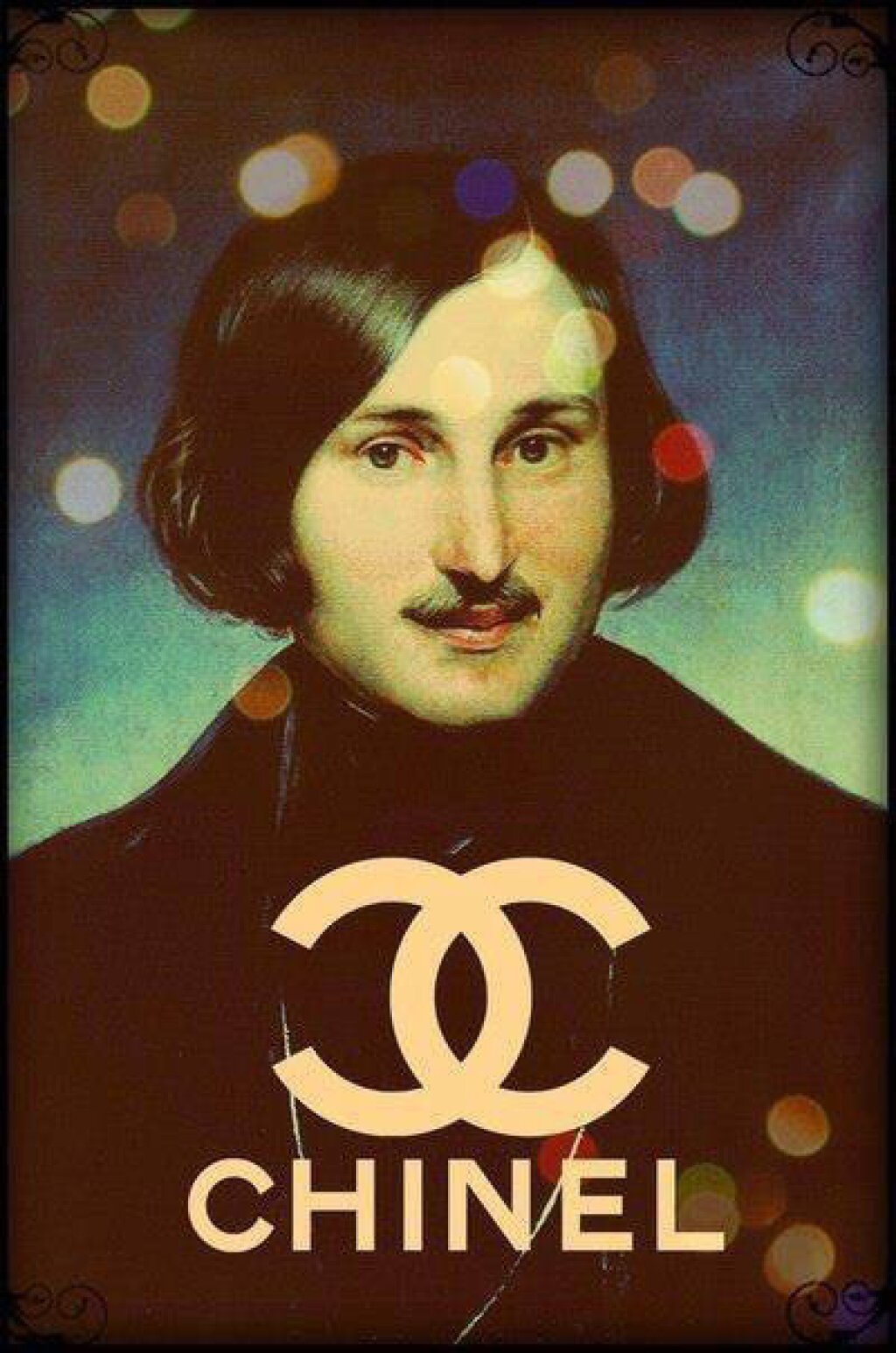

Interest in Kharms, though, isn’t limited to academia or fringe culture. In Russian bookstores, I’ve seen Kharms displays large enough for the likes of Gogol, or at least the Swedish-thrillers-in-translation section. 2015 saw the (re-)edition of a major biography, Valerii Shubinskii’s Daniil Kharms: Life of a Man in the Wind, and 2017 a biographical film simply titled Kharms. In St. Petersburg, one can see Kharms’ work in production or join a street excursion called "Ha-ha-Kharms." This tour features stops at locations meaningful in the author’s life, a concept recalling the programmatic commemoration of "Pushkin places" during the Russian national bard’s 1937 Jubilee. We might expect the glasnost-era thrill of reading Kharms to have dissipated by now, but interest in the author only seems to be accelerating. Fulfilling his own memoir-cum-prophecy, Kharms has been born again — this time, as a quirky cultural phenomenon.

Yet the vitality of the Kharms cult has failed to make the poet a household name. Explaining my work on Kharms to Russian friends and acquaintances, I’ve occasionally met with enthusiasm, but more often, our conversations proceed as follows:

Acquaintance: What Russian authors do you work on?

Me: Right now, I’m working on Daniil Kharms.

Acquaintance: No, no, I asked what Russian authors, Russians.

At this point I explain that "Kharms" is a pseudonym, and that the author’s real surname is Yuvachev. "Yuvachev" sounds Russian enough to convince my interlocutor that I’ve understood the question — though usually not enough to relieve all suspicion that, in studying Russian literature, I’m somehow missing the point.

Though Kharms hasn’t become a mainstay of Russian mass culture, interest in his work transcends the Russian-language sphere. Translations of Kharms’ work for children and adults have proliferated in recent years, as well as extra-literary foreign interest: the rights to the 2017 film Kharms, a Russian/Lithuanian/Macedonian co-production, were recently bought by a Finnish TV channel. Kharms seems to be settling into his place in the Western literary canon, whether as a representative of the literature of totalitarianism, the literature of the absurd, or simply as a representative of commercial success.

Part of the charm, as it were, seems to derive from Kharms’ forbidden-fruit status. As a 2007 review of the collection Today I Wrote Nothing proclaimed, “Until recently, Daniil Kharms’ unsettling stories were best known to the Soviet secret police. Only now are they set to reach a wider public.” Indeed, few popular-culture discussions of Kharms can resist a gruesome recounting of his death in NKVD custody. It also doesn’t hurt that Kharms’ life, by turns whimsical and tragic, is well-suited to that internet favorite: numbered lists of fun facts, like this "seven things you didn’t know about Daniil Kharms" listicle that appeared in Rossiiskaia gazeta.

Though Kharms has now been freely published for thirty years and can no longer be considered either a novelty or a symbol of newfound artistic freedom, his work retains its cachet. Serendipitously, he seems to have anticipated the trends of post-Soviet literature that obtained at the exact moment he was "rediscovered" for mass publication. While his writing is often read as a continuation of the avant-garde or a forerunner of the French Theater of the Absurd, it also contains elements of the postmodern — from the close-to-empty signification of characters like "Pushkin" to the "fake-news" quality of his historical pieces. Kharms' proto-postmodernism acquires an especially ironic cast given its origins in the moment when the grand narrative of Stalinist modernism threatened to consume everything in its vicinity.

Unsurprisingly, wide popular interest in Kharms, combined with the political implications of his era, have created their share of generalizations. These include claims of the author’s (intentional) political activism: for example, a 2017 article in Russia Beyond the Headlines, quoting Kharms’ forced confession to the NKVD, argues that the “anti-sense” characterizing the poet’s work “was deliberate and was indeed intended to undermine the status quo.”

It might be tempting to draw politicized conclusions about Kharms that go beyond his own political context and into the present day. Could the popularity of an "anti-regime" poet signal growing sympathy for political outsiders (or perhaps those who are simply “against everything”)? Yet the Kharms cult, if indeed there is such a thing, seems restricted to elite circles composed of relatively well-off, already-politicized folks likely to reside in Moscow or Petersburg.

Though it offers little by way of political prognosis, resurgent interest in Kharms gives insight into another phenomenon: post-Soviet nostalgia. Nostalgia for Kharms, specifically, stretches the concept pretty far, since he was active during a period of which few people have living memory today and remained a virtual unknown rather than a staple of Soviet mass culture. But perhaps Kharms represents another kind of nostalgia for the Soviet space, one not limited to people who experienced the regime firsthand or even those inhabiting successor states.

Nostalgia for Kharms bespeaks a longing for a cultural phenomenon that hardly existed in well-defined form in its original 1930s manifestation. The reborn Kharms is fairly fluid and open to various interpretations — was he an anti-regime radical? A student of the Russian avant-garde? A forerunner of French absurdism or the Russian postmodern? Like any nostalgia in pure form, Kharms-centric nostalgia represents a temporal idealism that allows us to emphasize the best features of a given period while looking past its less desirable aspects. Taken to the limit, this mode permits the union of seemingly incompatible elements — according to its logic, there is no contradiction in, say, enjoying Kharms’ dark comedy while simultaneously admiring Stalin's managerial prowess.