Angela Brintlinger is a Professor of Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures at the Ohio State University. She blogs at manicbookstorecafe.blogspot.com.

In the old days, Russian women didn’t curse.

Or at least not out loud. Or in public.

For language learners the world ‘round, figuring out how to say the “bad words” is not just something you do as an adolescent. Everyone wants to know what to say when you drop a rock on your foot, or when someone steals your wallet in the metro. You don’t really feel “fluent” until you can curse when you make a big error.

My old Russian teacher told me of his classic humiliation in the Soviet Union of the 1970s: “Where can I go to spit?” he asked a hotel maid. “I brought my swim suit!” (The error was in placing the stress: плевáть versus плáвать.) That's the kind of error that makes you curse in your head.

I think back to my own cultural errors in 1989, when food distribution networks had gone haywire and sugar was rationed in Moscow. I travelled to then-Leningrad, only to be met with reproaches. “Why didn't I think to buy sugar for my friends to help out with the summer jam making?” I asked myself. I might have added something more pungent, like “s**t, I should have thought of that!”

In the wild mid-1990s, one of my friends got involved in complicated business dealings, which meant that she introduced me to some rather shady characters. I can still remember my shock when I met a woman who cursed so much that there were no regular words in between. That too, of course, is a form of social interaction. But for most Russians, and even for me, it was also a clear sign that these were not safe people to hang around with. (I escaped on an elektrichka at daybreak while everyone else was still drunk. But that’s another story entirely.)

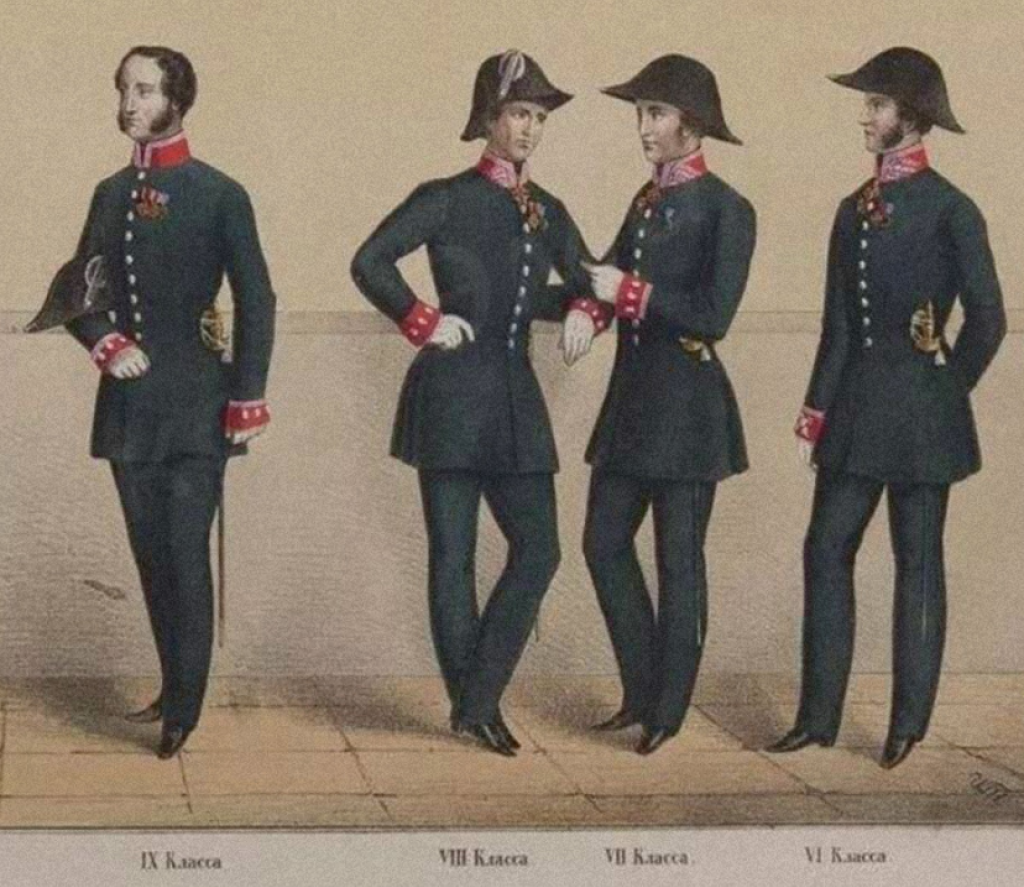

In Russian literature there were always very strict rules of decorum, especially for published texts. Not only no cursing, of course, but also no talking about anything too physical or intimate. And a lot of so-called Aesopian language, to get around the tsarist censors and then the Soviet censors.

So in Turgenev's Fathers and Children (1862) when Evgeny Bazarov realized that Anna Odintsova was hot, there were two different barriers to his expressing his arousal: 1) his professed “nihilist” beliefs that found anything that smacked of romance or love to be out of bounds and 2) the prudishness of Russian literary habits. Instead of “I'd love to take her to bed” he announced “I'd love to see that body on a dissection table.” Students are still horrified by his “medicalizing” attitude.

When Yury Trifonov's main character in his story “The Exchange” (1969) recognizes that he has changed due to the influence of his wife and her bourgeois family (the Lukyanovs), he doesn't say what a Phillip Roth character might have said: “She's cut off my balls!,” or “She's emasculated me!” Instead he resorts to satirical linguistic innovation: “I have become Lukyanov-ized.”

Throughout the Brezhnev years, even the rules of samizdat and tamizdat, of dissident literature, observed the same linguistic taboos. With the notable exception of Yuz Aleshkovsky, the Russian equivalent of four-letter words—“censor-able” (подцензурные) words—mostly stayed off the page.

Then came Gorbachev. I remember when glasnost’ really took off. Viktor Erofeev—that “bad boy” of the 1980s—had yet to publish his first novel, Russian Beauty, in which he depicts both sex with a dead/dying man (à la World According to Garp) and lesbian sex. But he was already competing for racy content. Claiming that Eduard Limonov was particularly proud of being the first to portray a homosexual encounter with a black man on a playground in New York, Erofeev figured he had gone him one better in his own short story “Berdyaev.” “I am the first person in the Russian language ever to depict the sound of urination,” he said.

Russia survived the chernukha era, and though there have been moments over the past twenty years that censorship again loomed, in post-Soviet times it seemed like Russian literature was going to be able to embrace a larger spectrum of linguistic options. In print and on the internet, profanity and perversity have prospered. Do I want to read Vladimir Sorokin's fiction about excrement, or about clones of Russian leaders who have anal sex? No. Do I want to teach it? No. Do I want it to exist? Absolutely. Not everyone agrees: in 2002 Sorokin was accused of pornography for his Blue Lard, and all over the world readers began to anticipate the renewal of Soviet-style censorship. And there were book burnings, but no one was put on trial or sent to Siberia.

However, in recent years, the lax standards of the post-Soviet era have been taken to task. In 2009, for example, Moscow State University professors noticed that in his book The Encyclopedia of the Russian Soul (published in 1998) their alumnus Erofeev had expressed what seemed to them to be extremist, “russophobic” and even genocidal views. Journalist Evgeny Nasyrov explained for the internet newspaper GZT.RU that a politician planned to investigate and even prosecute Erofeev for the contents of that book. The professors who signed an open letter, in Nasyrov’s words, found that “the writer’s already impoverished language … is liberally seasoned with lexicon that violates the norm, with unprintable words. There are pages of the book where [such words] make up approximately 25% [of the text].”[1]

All that is about to end. As reported this week, Putin’s new “bloggers law”—which goes into effect on August 1—includes a section on profanity. Four “vulgar words” will no longer be permitted. The New York Times explains: “(The words, not mentioned in the law either, are crude terms for male and female genitalia, sex and a prostitute.)”[2]

Really? We’re going back to х**, п***а, е****, and б***?

Don’t get me wrong. Even though my children think I have a potty mouth (I do tend to drop things on my toe fairly frequently or have other, unspecifiable reasons to expostulate loudly), I am no fan of profanity. The great and powerful Russian language, as Turgenev had it, has made a lasting impact on world culture even without those nasty words. And although I love postmodernism as much as the next girl, it can be difficult to structure a productive discussion in the university classroom about the “floods of liquid s**t” that engulf downtown Moscow in a story like Viktor Pelevin’s “Vera Pavlovna’s Ninth Dream.”

In the Times, Erofeev has the last word:

“We feel like we are back in kindergarten again when they said, ‘Don’t pee in your bed and don’t eat with your hands and don’t use that word,’ ” said Viktor V. Yerofeyev, a popular writer. “On the one hand, the Russian government says the Russian people are the best. On the other hand, it doesn’t trust the people.”

For lovers of Russian language and literature, for Russian speakers the world over, this is about more than just urinating on the page. And more than just trust. Linguistic norms reflect political, philosophical, existential freedoms. And even though the feces-and-urine school of Russian literature since the collapse of communism really has felt a little bit like kindergarten, the alternative is much, much worse.

[1] E. Nasyrov, “Прокуратура РФ изучит творчество Виктора Ерофеева” (1 October 2009) http://newsland.com/news/detail/id/417771/

[2] Neil MacFarquhar, “Russia Quietly Tightens Reins on Web With ‘Bloggers Law,’” New York Times 6 May 2014.