On June 19, 2017, the University of Bristol hosted a research workshop titled “Beyond Putin: Masculinity in Russia, Eastern Europe and Eurasia” as part of a series on Transnational Masculinities. Rather than focus exclusively on contemporary Russia, the workshop included papers on masculinity in medieval Rus’, the Soviet Union as well as post-socialist societies including Croatia and Georgia. The audience—some two dozen in number—included Slavists as well as those interested in masculinity studies more generally. Here, Katherine Dunleavy, a PhD candidate in Classics at Bristol working on masculinity in the Roman world, reports on the event for All the Russias.

This workshop examined concepts of masculinity in Russia and Eastern Europe. It set out to address pertinent questions around the relationship between gender identity and national identity, and the tensions between liberalism, often associated with the West, and nationalist traditions.

First, Nick Mayhew (Cambridge) illustrated the way the contemporary Orthodox church in Russia is constructing an essentialist masculinity through revisions to historical hagiography. The church reimagines saints joined in spiritual union as joined in a procreative marriage with a unification of bodies. He highlighted the state’s interest in this promotion of “traditional family values” and the way in which this approach limits criticism from historians within Russia.

David Gillespie, recently retired from the University of Bath and now affiliated as a visiting professor to Tomsk State University, focused on masculinity in Vasilii Shukshin’s Kalina Krasnaia [Snowball Berry Red], touching on both the novella (1973) and film version (1974). Gillespie introduced the concept of the alienated Russian peasant in an urban world as an exemplum of the tragedy of the Russian man in the twentieth century. He reflected the loss of rural traditions and a connection with the natural world that can never be regained.

We moved into Eastern Europe in the next paper from Catherine Baker (Hull). She highlighted the significance of the military in the performance of masculinity and the way in which soldiers can embody the state in militarization. Looking at contemporary musicians with a military background and Croatian nationalism, she suggested that military aggression can be found in the aesthetics of the metal music scene where folklore and fantasy, warrior aggression, and nationalism are embodied in the performance.

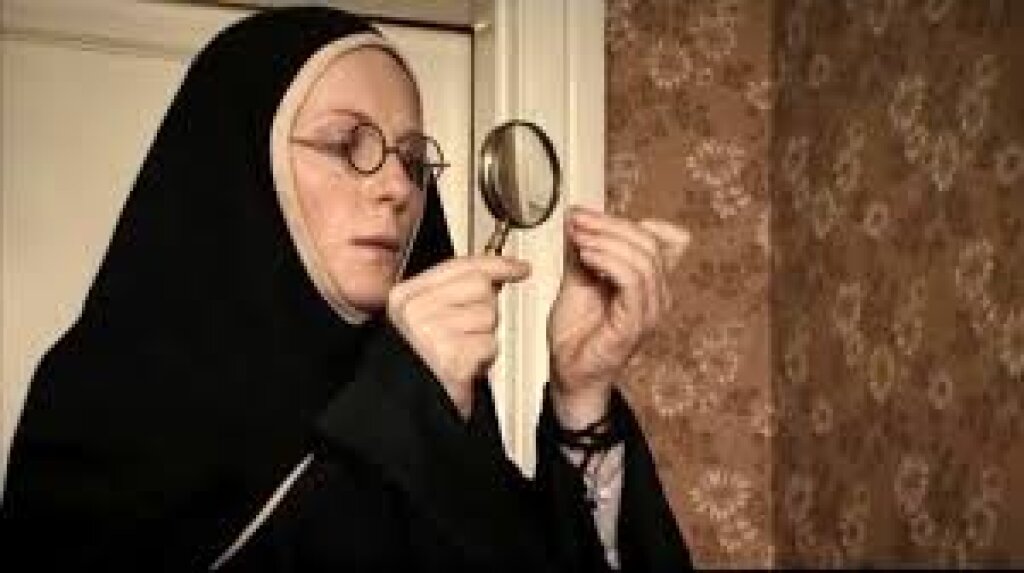

Constanza Curro (UCL) wrapped up the presentations with an exploration of masculinities performed in Georgian public spaces. She demonstrated that Georgian masculinity is significantly different to Soviet masculine identities based on work and status. Instead, Georgians value wit, cunning, loyalty and honesty; these qualities can be seen in social gatherings of men that act as bonding and sharing experiences. These performances, however, have declined due to state ideologies that prize industriousness and modernity in a drive to become more western.

A clear theme emerging from the papers and the following discussion was that of authenticity: what does it mean to be a “real” man in different cultural contexts and how is seemingly authentic masculinity given validation? This discussion raised issues around rituals of masculinity which were covered in all papers, through musical performance in Baker’s presentation and group bonding activities in Georgia presented by Curro. Questions around who has the right to validate masculinity—is it the state and the church—were raised by Mayhew, and Gillespie suggested that the removal from the land and social rituals can call into question apparently authentic masculinities.

One of the most significant comments in the discussion around the performance of masculinity highlighted the tendency to look for validation in the past, not in an objective version of history but in nostalgia, tradition and, even, historical revisionism. This issue seemed particularly pertinent to former Soviet states where changes in state ideologies and conservative bodies (such as the military and the church) have been highly significant in changing perceptions of gender in relatively short spaces of time. The workshop demonstrates that there is much left to explore in this area and that Eastern European contexts raise many critical questions about masculinities, particularly in the relationship between performances of masculinity and institutional structures, whether military, state, or religious.

This workshop was generously funded by Bristol’s Institute of Advanced Studies (as part of their ‘Transnational Masculinities’ workshop series) and BIRTHA, the Bristol Institute for Research in the Humanities and Arts (‘Eurasian Connections’ series). The workshop was organized by Dr Connor Doak and Dr Bradley Stephens, co-founders of the Men and Masculinities in Culture & Society (MMICS) Research Network. For further information, please follow us on our Facebook page and Twitter account.

The featured image depicts a Georgian tamada (toastmaster) by Oskar Shmering (1863–1938).