Nicole Disser is a Master's Student in NYU's Global Journalism Program and the Department of Russian & Slavic Studies

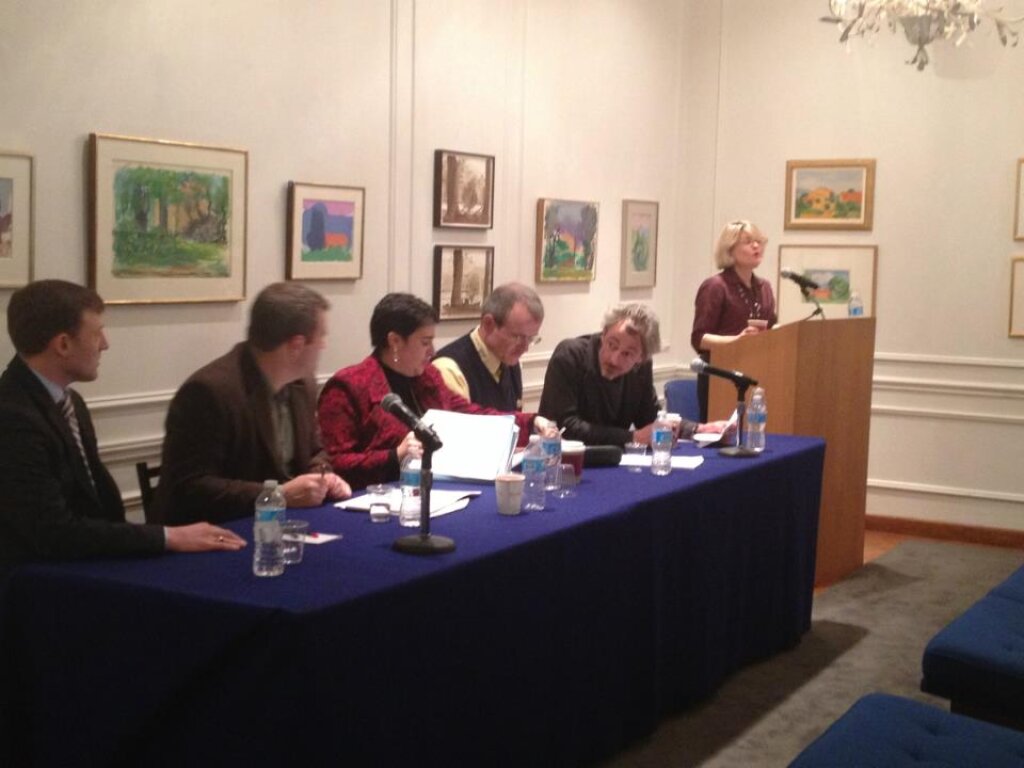

Saturday’s panel “Homefronts”, part of this past weekend’s international symposium Cultures of War: From the French Revolution to the Russian Revolution, saw a lively discussion of the domestic experience of war, focusing on the social consequences of mobilization for warfare. The panel referenced the resulting destabilization of society in its many forms, from the transformation of gender roles, to the more measurable effects of inflation, and, of course, the potential political consequences. The speakers came from a variety of backgrounds, with expertise in Russian literature, history, and French military history. The various "homefronts" treated by the panelists ranged from the Napoleonic siege of Moscow in 1812, to Russia during World War I, as well as the post- World War II experiences of France in Algeria and Indo-China.

Wynne Beers, military officer and Professor of History at West Point, contended that the homefront has become less relevant for Americans today. Conscious efforts to change behaviors within the domestic sphere for the purpose of contributing to the war effort in ongoing conflicts have all but disappeared from the American scene.

Yanni Kotsonis, Professor of History and Russian & Slavic Studies and Director of the Jordan Center, disagreed, arguing there is always a homefront, and the effects of war can never be completely prevented from making their way to the people back home.

Anne Lounsbery, Chair of Russian & Slavic Studies at NYU, questioned the very definition of the homefront, highlighting the fluidity of the concept. The panelists opinions on this point appeared to diverge. Beers argued for a simpler, less flexible definition of the homefront: efforts such as civilian participation in arms manufacturing and the rationing of certain materials, with a conscious realization that individual, civilian activity at home directly contributes to the war effort.

Notre Dame History Professor Alexander Martin pointed out the German word for homefront, Heimatfront, literally translates to “homeland” front--which removes the concept from strictly describing the domestic sphere, suggesting that "homefront" describes the experience of everyone in a given country who is not elsewhere fighting the war.

Other panelists disagreed. Joshua Sanborn, Chair of the History Department at Lafayette College, was of the opinion that the homefront has implications that specifically impact the domestic sphere; the idea of a homefront is a feminization of war, while also being representative of society-wide consequences.

Sanborn discussed the various transformations of Russian society as a result of the retreat of the country's 1915 retreat. He specifically focused on what he called "decolonization," and the resulting changes in ethnic relations.

West Point History Professor Greta Bucher raised a particularly interesting topic: the impact of war on gender roles. Bucher made comparisons between France and Russia after World War II, examining the impact of the war on gender roles. She spoke of a “crisis of masculinity” experienced in both France and Russia, and argued the experiences for women were somewhat different in the two countries. The impact of postwar family policies in the two countries diverged significantly. Whereas in France, these were implemented, in Russia they weren’t actually carried out. Bucher also noted official family policy wasn’t a new concept following World War II. In effect, it has been around for centuries, though in different manifestations, notably in church doctrines on family relations.

Martin looked at the impact of war at home through a literary lens. Martin examined memoirs and journals of the Russian middle classes, (though he was careful to point out such a class did not really share the same characteristics of what we now think of as the middle class) prior to and following the War of 1812. What he found was a unified sense amongst the authors that there was a systemic collapse of order, which in turn signified that a civilized environment had existed in the first place. There had to have been a sense of stability and order for there to be a sense that things were “messed up”, so to speak. Because of the war, the “middling class” was subject to abandonment by both the elites and looting by the lower classes. What he found was a strong sense that things had fallen apart, and people at home experienced the tangible aspects of destabilization caused by the war for years to come.

The panel discussion was an interesting exploration on the topic of homefronts, highlighting some of the impressive work being done in the field of Russian history and literature studies. It was also indicative of the need for further research into the topic so that some of the more disparate homefront experiences throughout history will have a common language by which to compare the differing consequences of warfare on society.