As the noose tightens around the Trump administration, and most of my friends place their bets as to which enabler is going to take the fall next (Go, Jared!), I worry that some Western pundits have gone overboard. While investigating or critiquing alleged collusion with Russia, we need to be careful that we are not inadvertently bolstering the Russian case for American and European paranoia. We may not be colluding with Russia, but we are handing over propaganda victories free of charge.

I’ve written about this before. But just when I thought I was out, a December 1 op-ed piece in the Washington Post pulled me back in. In “What Russian Collusion with Hitler Reveals about Interference in the 2016 Election,” Professor Thomas Weber, an accomplished and respected historian at the University of Aberdeen, connects the dots between early Russian nationalist support for Hitler and…Fancy Bear?

Weber is quick to point out that he is not engaging in “yet another ill-judged Hitler-Trump comparison.” While I have no doubt that Trump himself would find some “good people” among the SS (at least the Nazis weren’t Mexicans), Weber’s restraint looks promising. Instead, Weber engages in more novel, but more dangerous, historical parallels.

,,,the real significance of Hitler’s secret Russian collusion does not lie in shedding light on the challenges President Trump poses to American democracy, but on the strategic challenge that Russia poses to the world. For there is a line of continuity from the collusion of Russian nationalists with HItler in the early 1920s, to Joseph Stalin’s secret pact with the Nazi leaders in 1939, to President Vladimir Putin’s conduct in Ukraine and his interference in the elections in the United States.

Apparently, Russia (in all its forms, Soviet and post-) is a serial colluder. “If it’s ostensibly good for Russia, it’s full steam ahead, regardless of the consequences for everyone else.”

Where to begin? First, this description of Russia’s blind self-interest could describe any number of sovereign states, including the U.S. My point is not to engage in “whataboutism”—the fact that a flaw criticized in one country is shared by others does not negate the critique. But what it does negate is any claim that there is something peculiarly “Russian” about this behavior.

Second, Weber asserts that “there is a line of continuity” stretching from the 1920s to last year’s election, but that line seems to exist primarily in Weber’s imagination. Geometry tells us that if you see two points, you can put them on the same line, but it doesn’t mean that you have to. Instead, I suspect the flaw in Weber’s piece stems from a desire to present one’s own historical research as relevant to today’s world. This is an impulse I applaud, but in this case, it is one that would have been better left suppressed.

Why? Because the Russian state media have an all-purpose answer to attacks on Putin’s foreign policy, on the stifling of dissent and the violation of civil liberties, and especially to allegations of Russian interference in American political life: Russophobia. In August, 2016, the Russian Ministry of Culture even allocated 1.75 million rubles for a study of “technologies of cultural Russophobia and state-administrational responses to this challenge”.

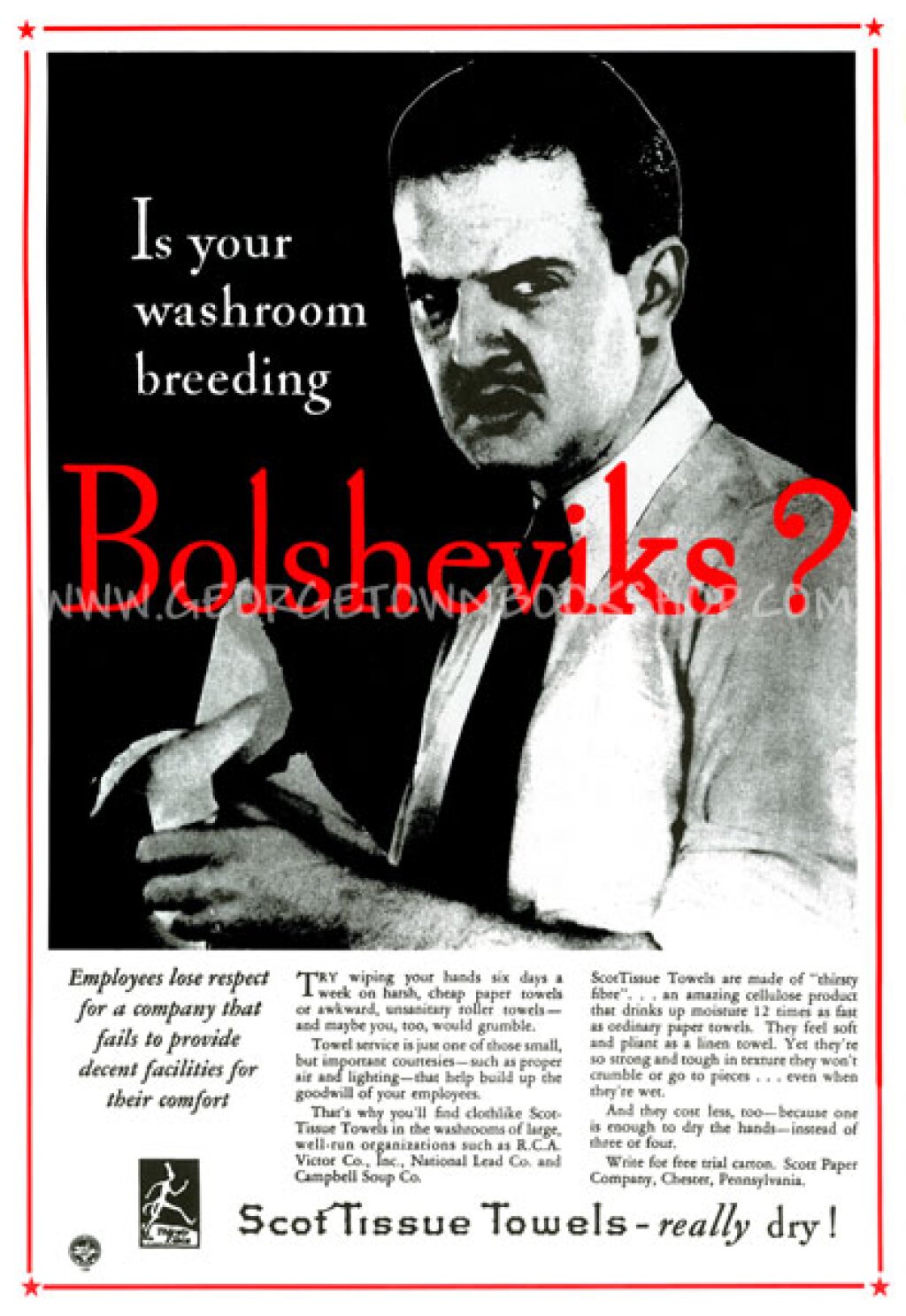

Is Your Washroom Breeding Russophobes?

If the Russian media are to be believed, virtually the entire Western world suffers from inexcusable bigotry. No, not racism (racism? what racism?), not anti-Semitism (don’t get me started), and not homophobia (thanks to the “gay propaganda” law, they’ve got that one covered). The real cancer in the Western body politic is Russophobia.

Like so many marginalized ideas, “Russophobia” has moved from the fringes to the mainstream since Putin came to power. The term was coined in the 19th century and revived in the 1980s in a book by the dissident mathematician Igor Shafarevich. While Shafarevich’s own ideas about Russophobia are not important here (ok, I’ll give you a hint: it’s the Jews’s fault), he supplied a useful addition to the Russian political vocabulary. Russophobia has become an all-purpose, blanket explanation for any disapproval of anything done by Russia or Russians.

Russophobia need not be explained or proven to be invoked and possibly believed. It turns a basic, paranoid subject position (the world is against us) into both an affirmation of the paranoid stance and the motivation for the enemy’s attack. As a concept, Russophobia does not require a full-fledged conspiracy theory to justify its invocation, but what it does provide is, if not an ideology, than an ideological placeholder that covers all “anti-Russian” sentiment or activity.

I spend a ridiculous amount of time and energy arguing against the validity of the “Russophobia” hypothesis, and I don’t have any reason to believe that Weber himself is Russophobic. But arguments based on a vague notion of historical continuity threaten to reduce Russia to a fixed essence, to an orientalized Other whose motivations turn out to be independent of historical circumstance. If the Russian government interfered with the American elections, the reasons have nothing to do with the actions and motivations of nationalists in the 1920s or of Stalin in 1939.

The Russian media’s spinmeisters are well-funded. So let’s not do their work for them.