Tonight, the poet and writer Alexandra Petrova will appear at NYU's Jordan Center to speak on her tour-de-force novel Appendix (NLO, 2016). In anticipation of her visit, All the Russias is pleased to feature an excerpt from Appendix — one which, not coincidentally, addresses the titular organ. The translation of this segment, which occurs early in Petrova's novel, is the work of a collective of translators including Martha Kelly, Ainsley Morse, Anastasiya Osipova, Kevin Platt, Maya Vinokour, Michael Wachtel, and other participants in an AATSEEL 2018 workshop organized by Ainsley Morse.

I felt even worse about my appendix. Over and over, they’d told me: “Don’t swallow fruit pits, and make sure to shell sunflower seeds before sticking them in your mouth, otherwise your appendix’ll get inflamed.”

But secretly, I would consume not only ordinary cherry pits, but also pages from my favorite books (no wonder they said I literally ate them up), pretty beads, little bits of earth — that is, anything marvelous but not dangerous.

I liked the idea that all of it was stored up somewhere, within some undiscovered sac inside my person.

In the story about Baron Munchausen, a single cherry pit, lodged in the head of a deer, sprouts into a whole tree. It seemed likely that I, too, contained seedlings that would someday break through and blossom fragrantly over my head as I went about my daily business. The parts of fairy tales I loved or feared the most found their way inside, only to re-emerge someday in the most unexpected way.

The glimmering, faceted glass of beads illuminated the murk of my gut.

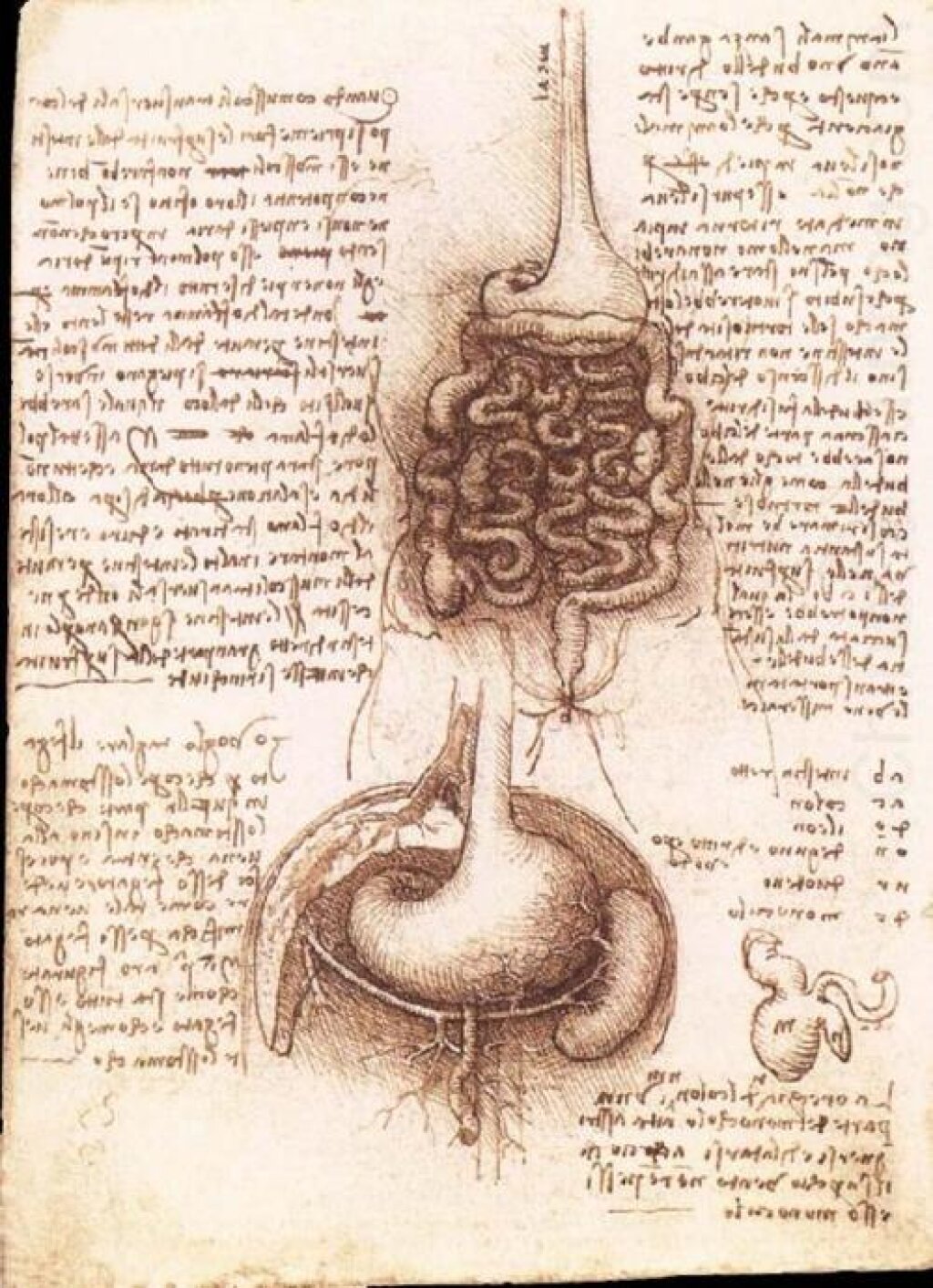

Our ancestors had once subsisted on grass and roots alone, which meant their intestine was much longer than ours. The material memory of this fact was contained in the appendix. Even though humans now enjoyed drinking the blood and chewing the meat of creatures almost identical to themselves, so that they had no need of a long hose for processing grass, for some reason it kept on appearing insistently within the body of every human specimen — as if to remind us of the unnaturalness of devouring flesh. The appendix was said to be a vestige. Shame can easily become vestigial. Once, back in school, they took us to view a concentration camp. People lived nearby, cooked their food, stood in line to buy bread more or less the same way as back then, when the acrid smoke of scorched Jewish and Gypsy meat had stood motionless, filling the air. It’s possible that some of them felt slightly nauseous, but that nausea produced no inquiries as to its origin.

They’d cut off a piece of me, even if it was a piece that evolution had rendered obsolete. That is, it was supposed to be obsolete, but I had long known that you could read something truly unimaginable if you stood on the wrong side of a cloth banner. More often than not, people looked out at the world and failed to see its multifariousness. No sooner did we leave our childhoods than we began to grow more and more alike. You could almost always predict how grown-ups’ sentences would end by the time they got to the third word — sometimes even by the second. In this paltry world, one had to seriously consider building a trampoline, a bunker, a dirigible, a nest — or just becoming a fast runner. Faster than a scooter or the speed of light. That’s what the pouch of my appendix had contained: the raw materials for building flying machines. It contained my dowry. The things it held transmitted to me the knowledge that, in fact, the national anthem didn’t always have to sound at midnight, that there was a place where you didn’t have to ask politely to be excused from the table or limit summer to just three months, and that’s if you’re lucky. There weren’t any months in that world at all, and even they did occur on occasion, it was in the guise of thmons or monthssssss, or snakes. And now my holiest of holies, my trampoline, my little lantern had been placed in a jar for all to see. From now on, my power would reside secretly in an anonymous museum and no longer belong to me. The appendix had been mine, the beads and pages from the Brothers Grimm inside it were mine, but now I’d lost my rights to them. My old life had been cut away and there was no way back. And in the new one — on the one hand — there were phantom pains stemming from the amputation of something on which I used to rely (the confidence of a gambler at the thought of her Swiss bank account, or a hamster stuffing seeds into its cheek pouch). On the other hand, I felt a new lightness. The loss of baggage aids in the growth of feathers on one’s back or on one’s sandals, as in the case of Mercury. In any case, from this day forward, I sought to renounce direct accumulation, which could always be tragically cut short, and rebuild from the ground up, relying on myself alone.