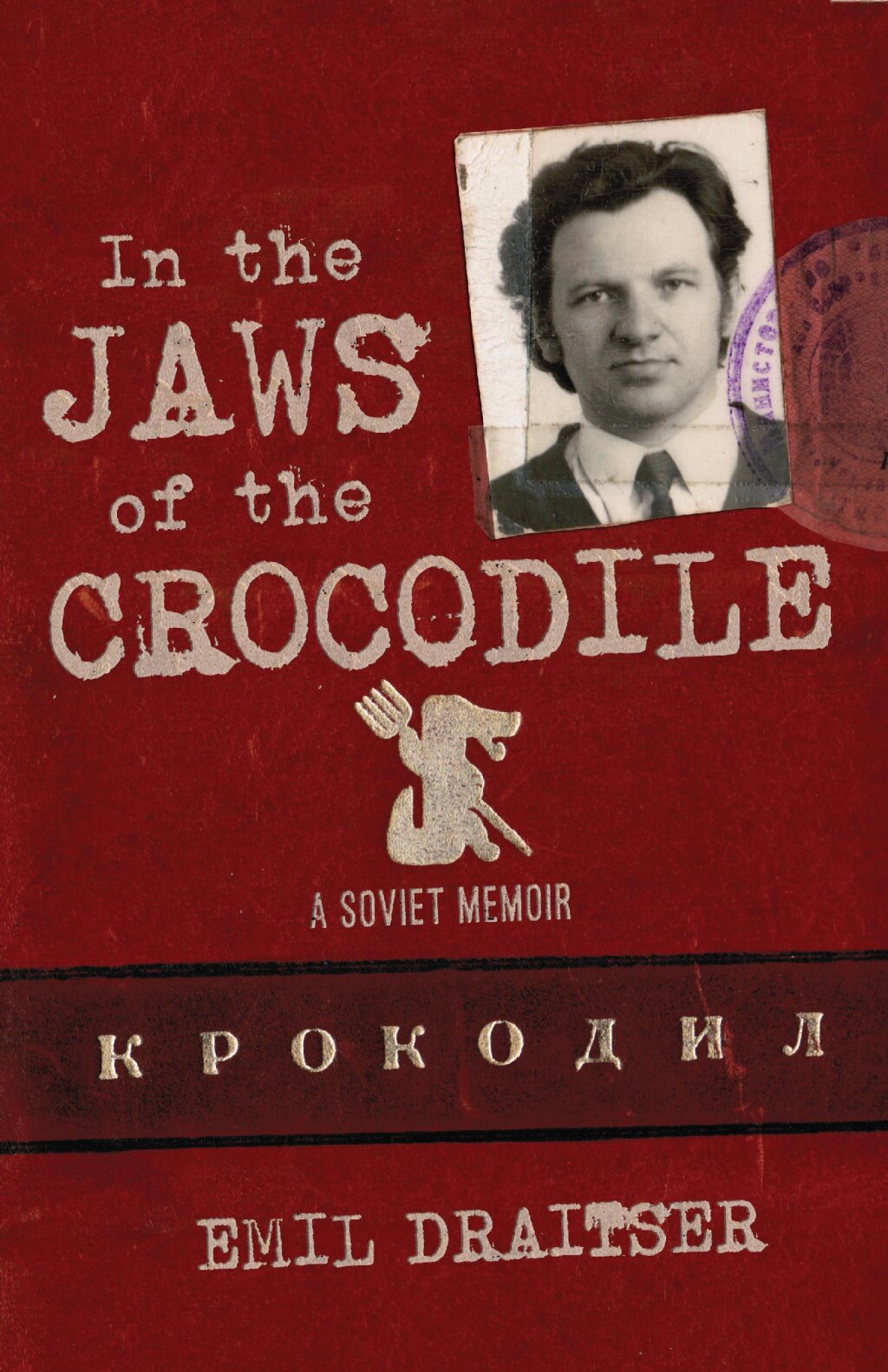

This week, All the Russias will be running a four-part series of excerpts from Emil Draitser’s new book, In the Jaws of the Crocodile: A Soviet Memoir, out this month from the University Press of Wisconsin. The action in the chapter takes place in September 1974, at the height of the Soviet Jewry Movement in America and worldwide. This book is the the sequel to his memoir titled Shush! Growing up Jewish under Stalin and the prequel to his autobiographical novel, titled Farewell, Mama Odessa, excerpts of which appeared in our Winter Reading Series in January 2020.

An exclusive virtual book launch will take place on Wednesday, February 3, 6:30 PM EST at the Shakespeare and Co. Bookstore in NYC. Sign up here.

Emil Draitser is an author and Professor Emeritus of Russian at Hunter College in New York City.

This is Part I in a four-part series. Parts II, III, and IV will follow on Wednesday, 1/27; Thursday, 1/28; and Friday, 1/29, respectively.

Chapter 24. A Small Iron Door in the Wall

“So, young man,” the KGB major says, stretching his hand toward my briefcase, “let’s see what you’ve tried to smuggle into the embassy of a foreign power.”

It happens sometimes that way. You set off on a journey in inclement weather. Before stepping outside, you gather all your internal forces. Ready to fight the elements, you raise the collar of your coat and pull down your hat as far onto your head as you can, almost to your eyes. But soon after you start, the weather changes for the better. The clouds disperse, the sun peeps out, there’s a gust of a tailwind, a happy coincidence—and you reach your destination much sooner than you had expected.

That’s what happened. It’s May 1974, and I’ve filed my exit visa application for my family and me. I’ve been preparing myself for the authorities’ decision for a long time. I tense up, thinking about what I would do if they turn me down. There is no reason to expect they would deny my request. I’ve never been privy to any state secrets. However, they turn people down for no reason. They refuse you just to annoy you. To let you know it isn’t a sure thing to apply and leave. Any applicant risks rejection, which means to be forever marked as politically unreliable.

To prepare myself for such an eventuality, I have made friends with a few refuseniks, people who weren’t permitted to emigrate. I have let their courage rub off me.

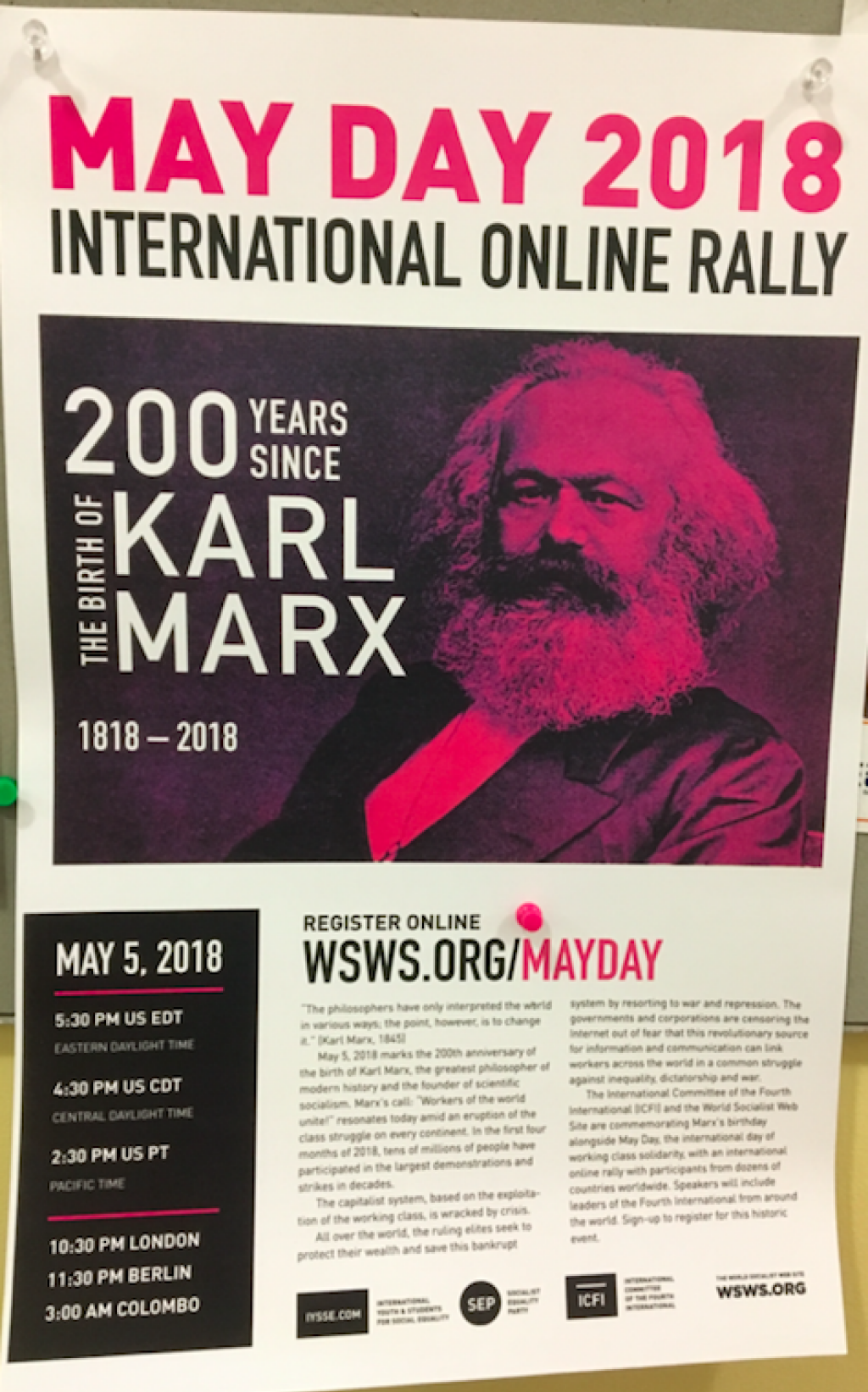

But something unexpected happens. After only three months of waiting, I get permission to leave the country. The reason for my lucky change of fate will become clear later. Right then, American lawmakers were discussing the possibility of amending the Trade Act of 1974. It concerned the granting of preferential status to Communist countries. Henry Jackson, a senator from the state of Washington, and Charles Vanik, a congressman from Ohio, thought it would be wrong to grant such a friendly status to countries that treat human rights, including the right to emigrate, like a doormat. During the debates, the senator has expressed his belief that, in such countries, people vote only with their feet, moving toward the state border.

Put yourself in the place of Soviet authorities. What should they do now? On one hand, the Soviet Union is the best country in the world, but, on the other hand, there are people who want to run away from it. No, no, ladies and gentlemen! Nothing like that! If there are oddballs, freaks, and yo-yos who apply for emigration, they’re just a pitiful grudging few. Their ties with family abroad force them to leave our great country. The ruling for the public at large is this: “Based on humanitarian grounds and in the interests of family reunification, the Soviet Union grants some ethnic minorities permission to emigrate to capitalist countries where they are the majority.” They include Armenians, Germans, and Jews in this group. To be sure, there are plenty of Armenians and Germans happy to flee the country. Mostly, though, they have been added to this list just for show, to cover up the Jewish character of the movement for the right to emigrate.

So, I receive a message from the Office of Exit Visas. They inform me that I should pack up and ship off while the going is good, within thirty days. With butterflies fluttering in my stomach—not just a few of them, a whole swarm rushing around in there—I head for the Dutch embassy.

What does the Dutch embassy have to do it with it? Like everyone else, I’m leaving the country on an Israeli visa. However, the Soviet Union broke diplomatic ties with Israel over seven years ago. In the course of the 1967 Six-Day War, fighting neighboring Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, Israel had turned the Soviet military equipment sold to these countries into a mountain of junk. Now, with the emigration ban lifted, the Dutch embassy steps in to help the emigrants with travel documents.

So, together with the butterflies, I set off to visit the Dutch embassy to process our visas and, if possible, ship my manuscripts out of the country. I believe that my writing life as I have known it has ended. My desire to save a pile of papers with notes made on various occasions serves no practical purposes. It is nothing more than a spasmodic willingness to preserve part of my old life on the eve of my future life, full of the unknown.

I could try to follow the established law. I could present my papers to the Glavlit, as the leading Soviet censorship office calls itself. (Its full name is “General Directorate for Protecting State Secrets in the Press under the USSR Council of Ministers.”) They would check out my notes, and, if they found nothing seditious, they’d stamp each page with their seal—and there you go. . . .

I have no desire to do that. First, if you hand over your papers to the authorities, God knows when you’ll get them back. If you get them back at all. . . . What Soviet institution, especially one as formidable as the Glavlit, ever abides by the country’s laws and regulations? And for people who have turned down Soviet citizenship, the authorities could send the papers straight from the receptionist’s desk into the office stove. At least some good would come of them—to warm up the gentle censors’ fingertips at the stove tiles.

Second, there are my diary entries, all too personal to be read by strangers. It would be like stripping naked in public. I’ve noticed no exhibitionist impulses in myself. Since childhood, my mother has reproached me for being too secretive.

And third, there are short satirical pieces from my most recent writing stint, the era of writing “for the desk drawer.” The Glavlit might consider them provocative. Not only would they not allow me to take my papers out of the country but they might also allege that I harbor the desire to smuggle my writing to the non-Soviet world to badmouth the Soviet state, just like the seditious authors I’d read about in the papers. I am mindful of the possibility that, instead of being sent to the West, I might wind up going in the opposite direction in a freight car marked “40 people, 8 horses.” They use such wagons not only to move troops during wartime but also to take prisoners to the gulag.

What could I do? How could I bypass Soviet red lines? The question isn’t new. It is as old as Soviet power itself. Since the USSR came into being, the whole population of the country has been thinking about this from dawn to dusk. . . . However, it has become known among emigrants that, when visiting the Dutch embassy, you can ask to ship some of your papers across the border in diplomatic pouches.

From In the Jaws of the Crocodile by Emil Draitser. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.