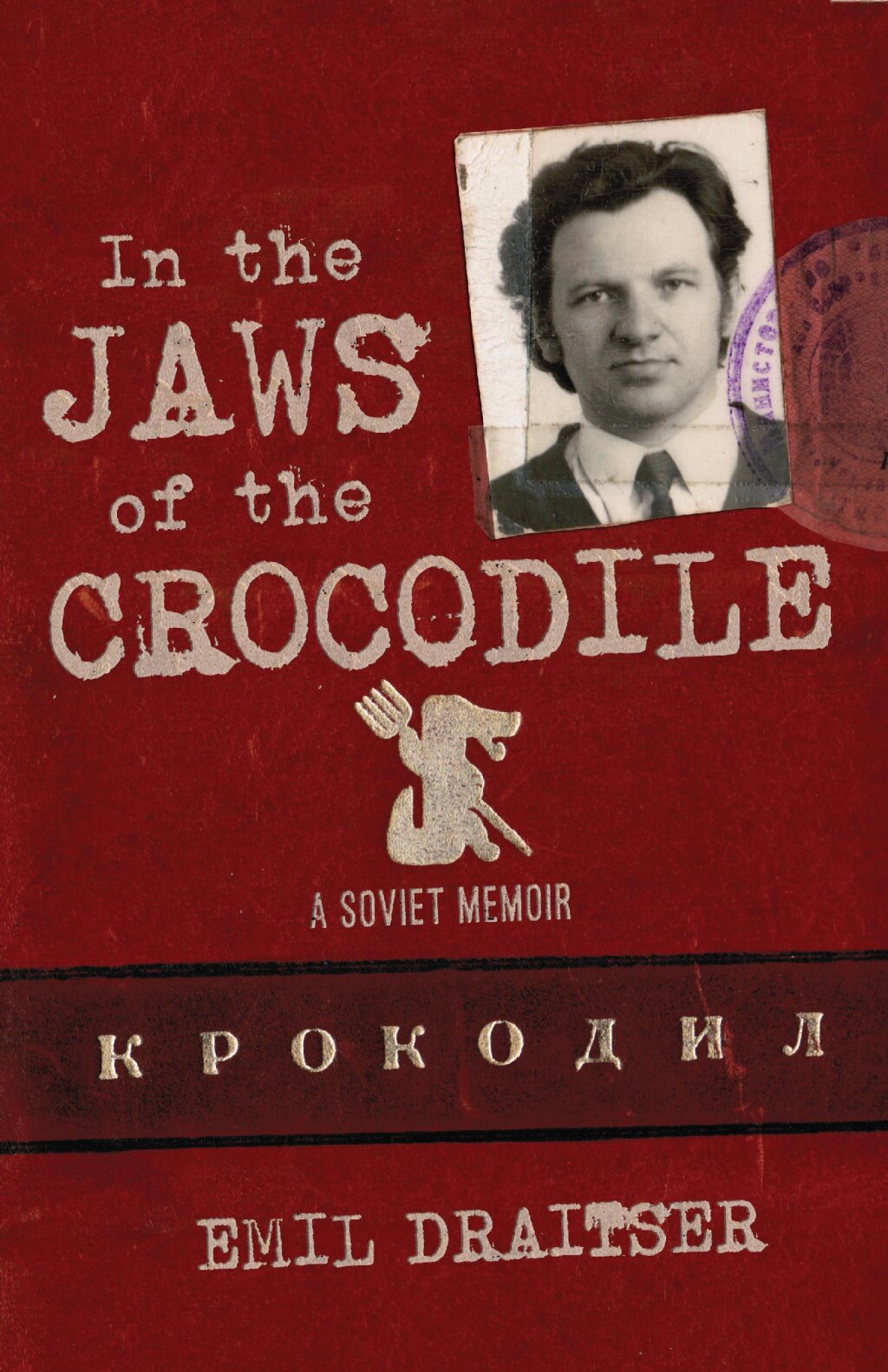

This week, All the Russias will be running a four-part series of excerpts from Emil Draitser’s new book, In the Jaws of the Crocodile: A Soviet Memoir, out this month from the University Press of Wisconsin. The action in the chapter takes place in September 1974, at the height of the Soviet Jewry Movement in America and worldwide. This book is the the sequel to his memoir titled Shush! Growing up Jewish under Stalin and the prequel to his autobiographical novel, titled Farewell, Mama Odessa, excerpts of which appeared in our Winter Reading Series in January 2020.

An exclusive virtual book launch will take place on Wednesday, February 3, 6:30 PM EST at the Shakespeare and Co. Bookstore in NYC. Sign up here.

Emil Draitser is an author and Professor Emeritus of Russian at Hunter College in New York City.

This is Part II of a four-part series. Part I may be found here, and Parts III and IV will follow on Thursday, 1/28; and Friday, 1/29 respectively.

Chapter 24. A Small Iron Door in the Wall (Continued)

It’s mid-September. It is sunny, though, on the cooler side. The embassy is on Kalashny Lane, near the House of Journalists. I enter the embassy yard. Lo and behold! A long line of people stretches from the lobby under a flat awning all the way to the gate. Because Soviet life has made me accustomed to standing in lines of any length, I gird myself with patience and ask the usual question, “Who’s last in line?”

It’s clear I will stand here for a long time. It’s especially trying when you’re a nervous wreck. You’re about to leave the country where you were born and raised. You’ve never even put your foot on the other side of the state border. You know what the West looks like only because you’ve seen the Foreign Newsreels shown in movie theaters before the feature films. Those newsreels prove that living abroad is a nightmarish experience complete with flooding, tornadoes, earthquakes, and long lines for unemployment handouts. It’s no wonder you feel like exchanging a few words with people in line. No matter what you say, you share a common fate now. They are your future travel companions. It’s the eve of a decisive turn in their lives. They, too, have always been careful not to tell strangers they are filing for an exit visa. Who wants to become a pariah, an object of suspicion? Here, in line at the Dutch embassy, you can allow yourself to relax a bit. You are among comrades in arms fighting the same battle. You’re among those who, just like you, their eyes squinted, jumped into the unknown without a parachute. Now, you are about to take your final step in the home stretch. Get your visas and tickets—and, as the great Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov wrote more than a century ago on the eve of his exile, “Farewell, unwashed Russia!”

Some tall, squirrely man materializes next to me. Another émigré looking for someone with whom to shoot the breeze, to exchange meaningless phrases of the “fall has come very early this year, not at all on time!” type. The man is lean; his face is wasted, pale, and wrinkled, like old linen after a sleepless night. Like me, he carries a briefcase. It’s thin, worn out, and as crumpled as its owner’s face. A briefcase identifies him as a man of intense intellectual labor, which has worn out both his face and his briefcase.

A cigarette in the corner of his mouth, Squirrely (as I nickname the man) chats with me. He’s visited the Glavlit office and discovered that the line there to have your papers certified is too damn long. Where the hell can you find time for all these darn bureaucratic procedures! So many other things to take care of before leaving the country! I respond, nodding and telling him I’d also like to get some of my notes out of the country, but here, at the Dutch embassy, the line is also a mile long.

The owner of the thin briefcase wastes no time—as soon as my words hit his ears, he drops the sympathy act. He doesn’t nod, no moaning and groaning. At once, he straightens his body—he’s much taller than me, almost like a fire tower—and motions toward the gates.

At the entrance to the embassy courtyard, there’s a guard shack with a phone inside. An aging mustached policeman, his face pocked, languishes nearby.

I turn around to see the guard already cutting across the yard. He moves at a leisurely pace, in a somewhat dignified manner, as if in slow motion on a movie screen. His step is that of a confident man carrying out his duties, which in and of themselves he hardly finds delightful. Well, they call me, and here I come. . . .

Finally, he approaches us and, his hands folded, stops, looking at me apathetically. He also shows no regard for Squirrely (I imagine that all uniformed policemen think little of their chameleon-clad coworkers). Apparently, assuming that, when a uniformed cop is present, his civilian clothes acquire the power of police get-up, Squirrely says firmly, “Come with us!”

To make me move, he touches me gently, as if I were a young girl, at my elbow and adds: “It’s nearby.”

The guards approach me from both sides, grab under my arms, and escort me out of the embassy courtyard.

Outside the embassy gates, in Kalashny Lane, we first turn left, then right, and walk toward Suvorov Boulevard. We pass the House of Journalists, a vast mansion. We walk half a block and enter a small courtyard. It is walled off from the street by a stone fence overgrown with ivy vines, already kissed with fall’s ocher. Sharp, black cast-iron rods peek out from under the leaves here and there. A quiet little Moscow courtyard; it’s hard to imagine it’s a place where any drama, let alone a tragedy, might unfold.

The guards lead me to a small iron door across the gate. That the door is iron-clad tells me that, as soon as it slams shut behind me, getting back to freedom won’t be easy at all. “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here!” flashes in my mind like the sign over the gates of Hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy. As soon as I see that door, Valentin Kataev’s novel A Small Iron Door in the Wall springs to mind. Published several years ago, the book is about Lenin’s life in exile and “the great man’s struggle for the Party unity, for the coming revolution,” as the reviewers wrote in awe.

As I approach the door, I’m struck by the irony of the situation. In Kataev’s work, a small iron door in the wall leads to Lenin’s living quarters on some quiet Parisian lane where he plotted the October Revolution. More than a half-century later, Lenin’s secret police lead me, just one of many others eager to leave his creation, to another small iron door in the wall.

From his thin briefcase, Squirrely pulls out a huge key that seems as if it would open the gates to some medieval fortress. The architecture and buildings here aren’t medieval but feel just as ancient, having belonged to the Russian nobility in the early nineteenth century. I find myself inside a small room now used as a place to interrogate people pulled from the line in the embassy courtyard. It looks like the room has served as a courtyard janitor’s lodge. Only a few square feet in size, the place could barely fit more than a few brooms and a wooden snow shovel. There’s also an armchair, for, I guess, the janitor to rest during his breaks from cleaning.

Squirrely sits me down in the armchair. He lowers himself on a stool near the door and announces: “You’ll be waiting here until the KGB curator arrives.”

Wearing the same bored look on his face, the mustached policeman leaves.

I have to wait in this tiny room with the armored door for the whole of three hours. Why waiting so long? Because the KGB curator has his hands full with other detainees? Or because he’s napped longer than usual after lunching in his office? Or is it a way to torment me with suspense? My anxious gut tells me it’s the latter. Maybe they’ll drag me straight to the Lefortovo, the notorious prison in Moscow, or perhaps they’ll just beat me up and throw me out onto some quiet street. After giving it some thought, I rule out these brutal scenarios. I haven’t even taken part in public protests. If I’ve written something less than flattering about the powers that be, I have written it for the desk drawer.

My heart skips a beat. My writing pieces are here, in my briefcase, which I hold on my lap. Frantically, I sort out mentally what I have in there. “The Wheel” . . . A grandma rushes around the country in search of a baby carriage for her grandson. Well, it’s just a satirical piece about poor production and bad sales management. The Party ideologists have left some space for public criticism, as long as it fits their propagandistic formula, “less-than-perfect things, uncharacteristic of our system, still happen here and there in our country from time to time.”

From In the Jaws of the Crocodile by Emil Draitser. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.