This week, All the Russias is delighted to feature an excerpt from Jeffrey Brooks’ The Firebird and the Fox: Russian Culture under Tsars and Bolsheviks, just out from Cambridge University Press. The below segment derives from the epilogue.

Jeffrey Brooks is Professor of History at Johns Hopkins University.

The single most popular historical novel in late imperial Russia was not War and Peace but a story of folkloric origins that celebrated freedom and poked fun at authority with sidesplitting humor (for the era). The Legend of How a Soldier Saved Peter the Great from Death appeared in multiple versions from 1843 onward and drew upon the deep Russian traditions and mythologies of the heroic Fool – in sacred accounts, the Holy Fool (Iurodivyi); in secular tales, little Ivan the Fool (Ivanushka-Durachok). During the century of Russian genius roughly from 1850 to Stalin’s death a panorama of extraordinary cultural richness unfolded, with layer upon layer of innovation in the arts. Visual artists moved outside and beyond the academy to paint the Russian people and landscapes, then farther still to pioneer Primitivism, Constructivism, and Suprematism. Composers, choreographers, and dancers infused ballet with new themes, costumes, sets, and music. Writers offered masterpieces of Realism, honed the modern short story, and went beyond, turning to the fantastic to capture the surrealism of cultural life under Stalin.

Throughout, the creativity of high culture drew on the rich traditions of fable, oral culture, and popular tales that had stood the test of time. The resonance of tradition in high culture kept it alive even as common people moved away from the old to embrace the new. Newspapers, magazines, brochures, serialized novels, illustrations, and eventually films drew in thousands, then millions, of common readers and viewers. The burgeoning popular culture took inspiration from above, just as high culture drew on the visual and oral traditions. Art forms intermingled, creative men and women shared energy and ideas, and the circular flow of cultural influence from high to low and back again propelled the cultural system forward to new forms of innovation.

Orthodoxy and the autocracy shaped the Russianness of the cultural vitality of this century through their presence and even more so in their absence after the Revolution, as cultural communities confronted their heritage and its meaning. Yet the Russianness ran deeper than Church or state. Shared themes and exemplary characters that bear the deep imprint of Russian tradition surfaced again and again over the century, in new guises and fresh approaches. A multitude of works, both great and lowly, treated the tension between freedom and order – freedom, construed as agency, free will, and self-realization; order presented as the constraints and comforts of accepted norms and hierarchies. The Firebird, caged or free, captured or in flight, is central to this theme. So is the fox, who (usually) succeeds in securing her objectives by maneuvering within the established order. A similar array of works probed tensions around the issue of boundaries: the Self and the Other; the Russian and the foreigner; the audience for art and those outside that audience. Division and unity, an ancient philosophical question, had special resonance in a period of unending social change, intermixing of peoples, the contestation of national boundaries, and war. Finally, the pace of change in the arts constantly brought to the fore questions about the nature of art and the role of artists in society. Consideration of the roles of cultural actors roiled as economic and political change weakened inherited class categories and social strata, and debates arose again as new forces claimed privilege and power.

These three themes – freedom and order, the boundaries of self and society, and the societal obligations of art and artists – played out in an enormous body of creative work, from the ephemera of popular culture to the exemplars still recognized as masterpieces of literature, music, and the visual arts. These works’ treatment of core themes places them in a shared tradition, illuminating their creative heritage and their influence on subsequent art and artists. In an environment of rapid cultural, social, and political change, the creative endeavor of those at the bottom of the social scale nourished experimentation and expression at the top. Innovation at the top percolated down to the popular media and then recirculated throughout the system.

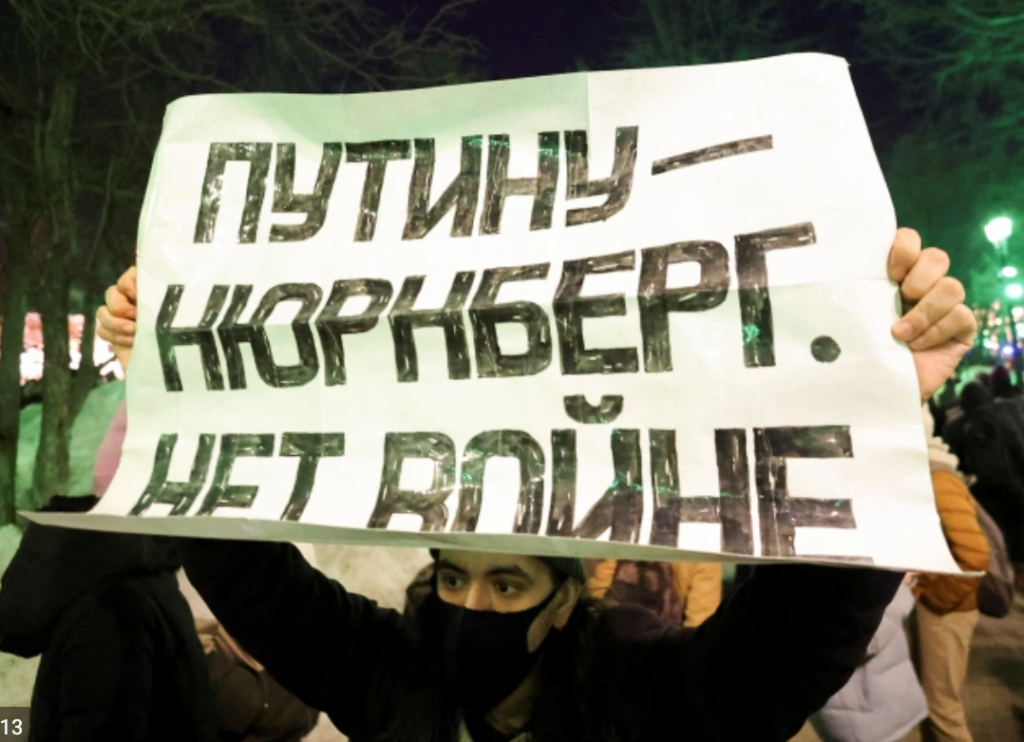

The works of this age of genius were created over decades, under conditions of recurrent social disruption and trauma: serfdom, Emancipation, urbanization, class upheaval, war, revolution, another war, another revolution, civil war, collectivization, forced industrialization, purges, again war, again purges, recovery, and the ever-present threat of the GULAG. In this environment, artists and authors reached back to tradition and forward to creative innovation to express themselves on the cardinal issues of their culture. Political constraint of the arts was a constant under tsar and Bolshevik alike, albeit with varying instruments and intensity. Although the works of high, middle, and popular culture of this period clearly fall within an integrated cultural ecosystem, the integration was not harmonious. A number of points of tension corresponded to the political fissures that ultimately erupted in revolutions, both failed and successful. Perhaps the most consequential tension was that between the tastes of common readers and those of the literary and cultural elite.

The new readers of the post-Emancipation period, whose numbers expanded rapidly, preferred accessible works within the Realist traditions of literature and the representational traditions of the visual arts. They had little patience for any of the modern “isms” in art or literature. They valued culture highly and sought to be accepted and respected as “cultured.” They resented what they perceived as condescension from the cultural elite. Their taste ultimately came to the fore as they rose in politics and the economy after the Bolshevik Revolution. Their views, expressed clearly even before 1917, identify them as the constituency that supported Stalin’s draconian crackdown on the creative arts.

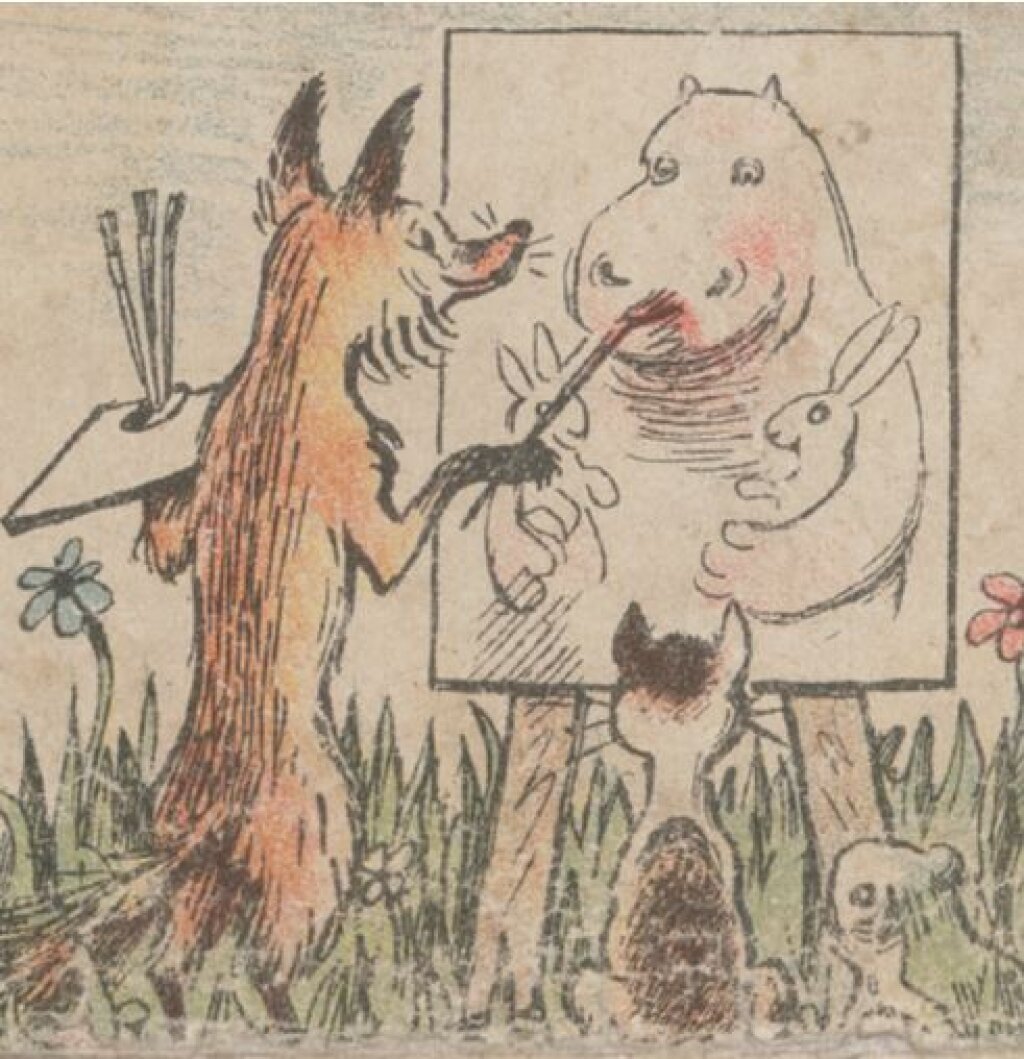

With the consolidation of Stalin’s control over the arts, much creative energy in literature, music, and illustration went underground. Among what remained above ground were works in translation and those for children, in the latter of which artists and writers could furtively celebrate the kindness and compassion that remained an enduring part of their culture despite strong countercurrents. Daniil Kharms, for example, celebrated tolerance and compassion in his tales for children such as First, Second (Vo-pervykh i vo-vtorykh, 1929). That he and others could do so at a time of officially sanctioned cruelty is a dimension of moral genius fully worthy of recognition and comparable to the lauded artistic brilliance of the age.