Part of an ongoing series about the question of “fake news”

Donald Trump has a knack for rendering otherwise neutral phrases toxic, colonizing them as though they were the site of a future white nationalist ethnostate. From “Believe me” to “beautiful” to “a lot of people don’t know,” innocent collections of words are now doomed to sound like quotes from our president’s 5th-grade vocabulary.

None of these phrases hold a candle to “fake news.” The term is unavoidable, thanks to the very real concerns about how lies get passed off as truth in social media, but it is hard not to hear the words as pronounced by late-night comedians working on their Trump imitations.

In this context, “fake news” is simultaneously fake and real—real, in that there is clearly a great deal of the stuff floating about and fake, in that Trump’s use of the phrase amounts to “they hurt my feelings.” When he’s not leveling the accusation at particular news media (notably “the failing New York Times"), he’s most often applying it to what he calls “this Russia thing about Trump and Russia.” And this is where we Russianists come in.

In my previous post, I speculated about the possible harm posed to liberal democracy by the hype surrounding “Russiagate,” a harm incurred even if all the allegations about Russian interference in American social media prove true. Russiagate makes conspiracy theorists of us all (even when the conspiracy is real).

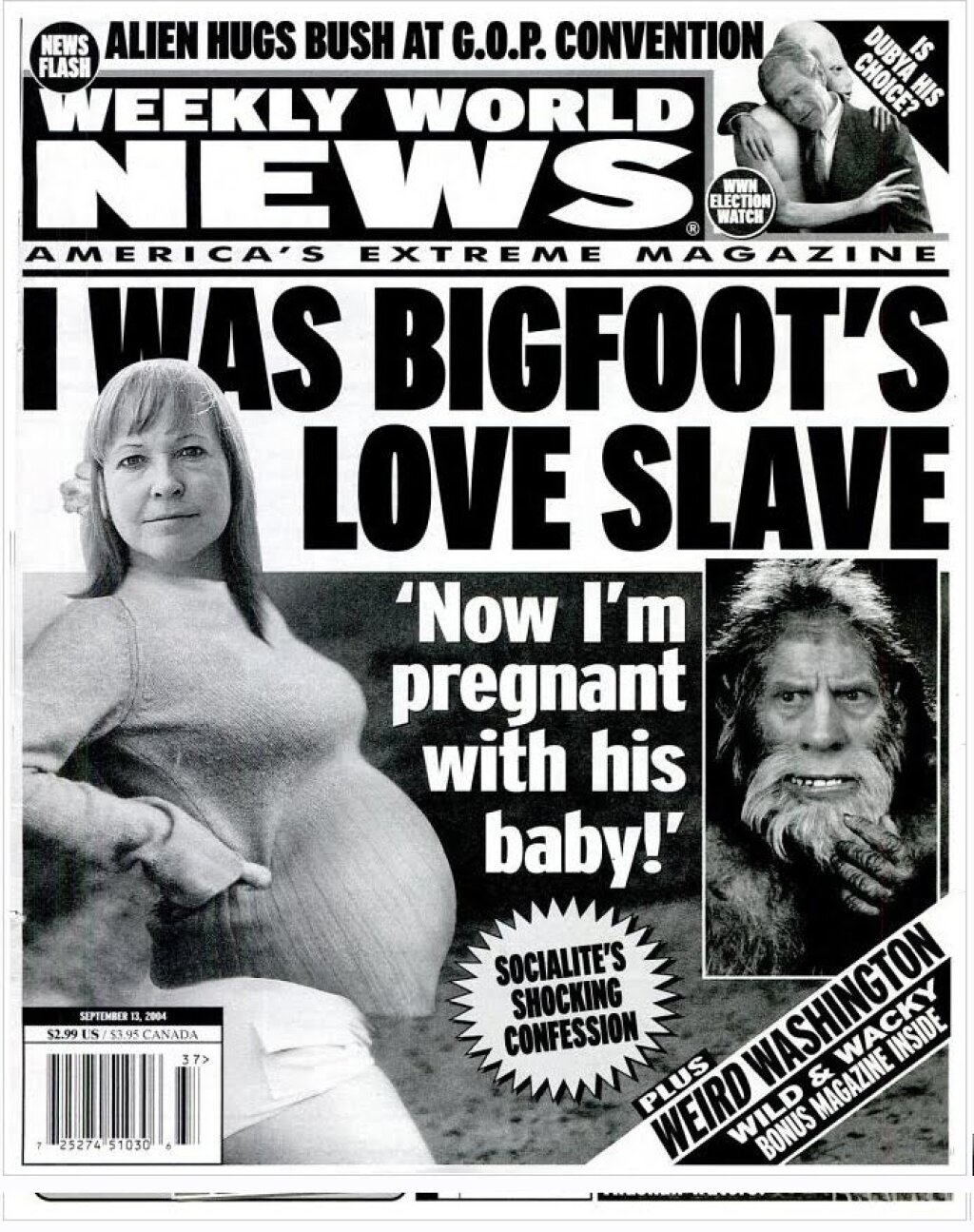

What, after all, is the difference between fake news and conspiracy theory? Well, one is news, and the other…may or may not be news. Fake news often traffics in conspiracy, while conspiracists thrive on falsified stories that they insist are true. At issue are the means of dissemination, as well as authorial intent. Because what they share is that both contain material that is easily debunked on the merits of logic, but consumed by audiences who are indifferent to evidence running counter to their worldview

Fake News and Moral Panics

Once fake news (such as the false news items allegedly planted by Russian trolls) becomes a topic of “real” news, we quickly find ourselves in an epistemological vortex, in which the report on a fake news item is itself construed as fake.

Being on the lookout for fake news requires that we assume what I have called the “conspiratorial mode:” without necessarily signing on to a full-fledged conspiracy theory, we at least temporarily take on a conspiratorial subject position (someone is plotting to trick us). While some fake news is motivated purely by profit (as in the famous case of the Macedonian teenagers developing American political click-bait for cash), by default we assume malign intent.

While it is still early days, the anxiety over fake news may have the makings of a moral panic. Moral panics don’t have to be 100 percent wrong. The 1980s panic over Satanic Ritual Abuse, which led to a wave of false convictions, was predicated on the realization that children actually are abused rather than simply fantasizing; in the American imagination, this abuse (more common in the home) was outsourced to the daycare center (a convenient locus of parental anxiety and desire). The perennial panics over teenage drug use, while often inflated beyond all reason (Reefer Madness) are still rooted in justifiable fears of real harm. Even the panic over comics in the 1950s reveals the adults’ real helplessness before a mass culture they are ill-equipped to understand.

If fake news is becoming the subject of a moral panic, then it is a meta-panic, because it is a panic about the very means that are used to spread panic (journalism and media-disseminated expertise). Most moral panics are about youth, but here, the youth is all of us. Social media are so new as to put all users in a position usually held by endangered children.

Paying the Trolls

Turning back to Russian manipulation of American social media: if it happened, it’s horrible (and it seems most likely to have happened). We might not be quite as alarmed if not for two things:

1) The catastrophic outcome (Trump as president)

2) Our inadequate understanding of how information circulates in social media.

In a race as close as last year’s presidential election, every relatively small influence on the outcome can be seen as decisive: Hillary Clinton would have won if people hadn’t voted for Jill Stein, if Comey hadn’t made his announcement about the ongoing email saga, if the candidate had campaigned in Wisconsin and Michigan, and, perhaps, if Russia had not interfered in American social media. Which one of these do we choose to blame the most?

On October 15, Russia’s TV-Rain interviewed a man about his year and a half working at the notorious Internet Research Agency's “troll factory” in St. Petersburg. The details are more than disturbing: the Agency’s guidelines target the main hot-button issues in American politics (LGBT rights, guns, taxes) in order to produce content that further divides the social media consuming public. The ex-troll’s lament about a change in management strategy (prioritizing quantity over quality) is almost comical in its resemblance to one of the most common complaints to come out of an office environment.

This bureaucratization is, in itself, revealing: the metrics here cannot gauge actual influence, only troll productivity (for more on this, I highly recommend the insider’s perspective provided by Vasily Gatov in a September 15 Facebook post). No doubt the Internet Research Agency’s managers are gleefully claiming credit for Trump’s victory (everyone wants a promotion or a bonus). But equating sheer productivity with effective results suggests a case study in bad management. Russia’s manipulation of our media is unacceptable, but it is also a generic hybrid: part Manchurian Candidate, part Dilbert.

“Beautiful Kate”

Looking at “fake news” as a Russia problem should not distract us from the larger question about the inherent vulnerability of our news ecosystem. Such a distraction reminds me of that master of distraction, Donald Trump.

On the campaign trail, Trump stoked up fears of the undocumented as violent criminals through repeated references to the 2015 murder of Kathryn Steinle in San Francisco by a Mexican residing there illegally (a crime given a great deal of coverage by Bill O’Reilly). While the murder of “Beautiful Kate,” as Trump calls her, was horrific, focusing on this case in particular makes it seems as though the biggest threat to the lives of young blonde American women were undocumented Mexicans.

By the same token, the biggest lesson to draw from Russian manipulation of American social media is not about fearing foreign attempts at subversion; the biggest lesson is that the entire system is subject to nonstop manipulation. As concerned as I am about Russia, I’m even more worried about Breitbart.