On October 23, the Jordan Center hosted a panel called “Russia and the 2016 US Presidential Election: What Happened, What do we Know, and What are we Going to Find Out?” For the better part of two hours, panelists Timothy Frye (Columbia University), Seva Gunitsky (University of Toronto), Julia Ioffe (The Atlantic), and Andrei Soldatov (Agentura.ru) discussed Russia’s role in the 2016 US Presidential campaign.

At first, it was academic business as usual. But halfway through the session, a woman in the back began heckling the panelists, shouting at them to speak up. They obliged, but to no avail: the interruptions continued. Then came the Q&A. The heckler stood up, triumphantly brandishing some leaflets she had taken from her bag. It was then that we learned, to our collective amazement, that there had been no Russian hacking in the 2016 election. “It was an inside job,” the heckler assured us. She then turned toward the panelists. “What are you all planning on doing about it? Do you want World War III? Where do you live? Do you ever leave your ivory tower?”

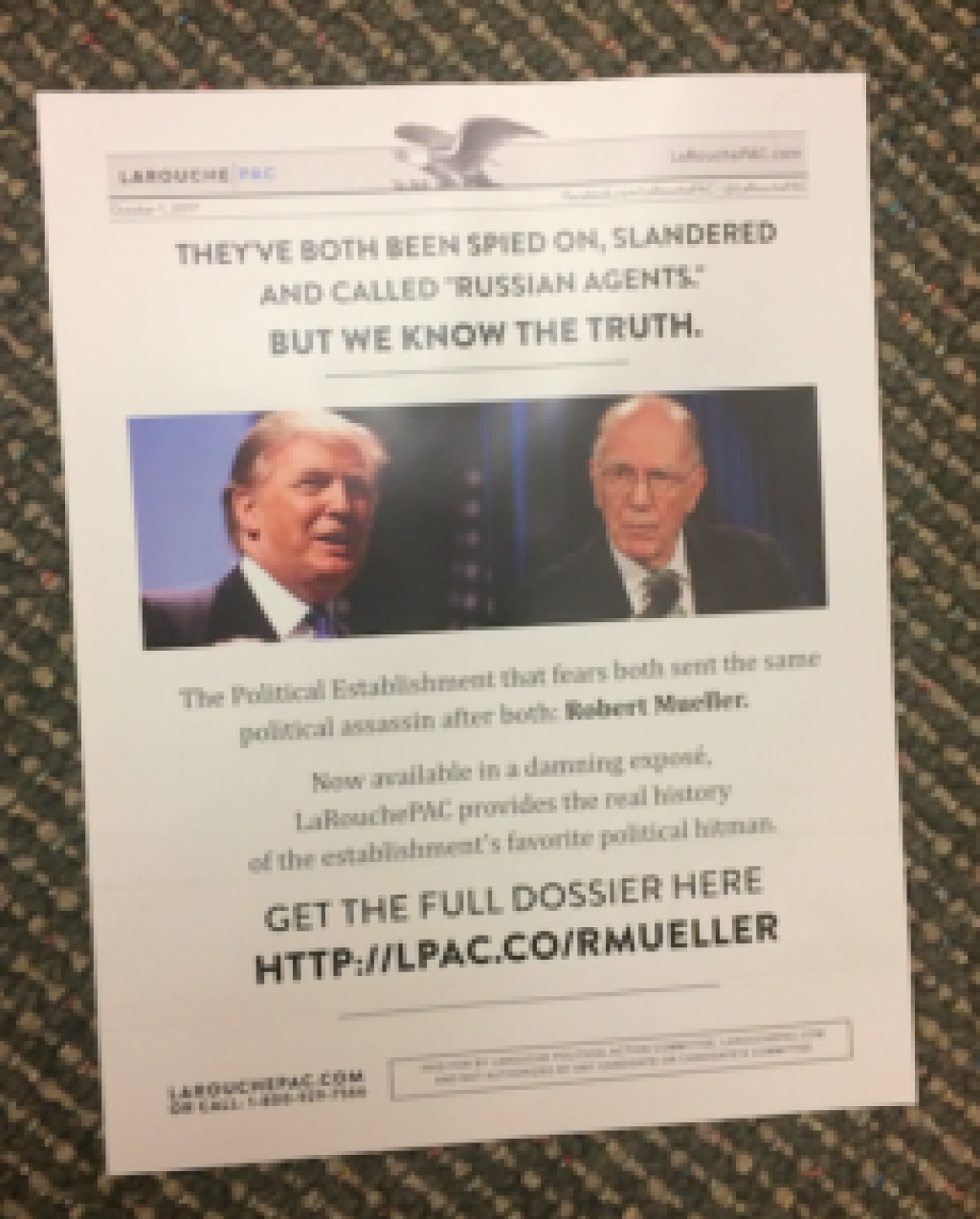

When we failed to appreciate her explosive revelations, the heckler grew indignant. Cursing under her breath, she stormed away, surprise accomplices in tow. Later, a faculty member discovered a flyer on their office floor — evidently, the brave truth-tellers had slipped it under the door on their way out of the building. It looked like this:

Lyndon LaRouche! Of course! Case closed. After this exciting turn of events, I sat down for a chat with panelist Julia Ioffe, staff writer at The Atlantic covering politics and world affairs. Our conversation is reproduced below, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

MV: I had a bunch of questions, but I’m going to change up the order because of what just happened. The first question is about civility in public discourse and especially in public discourse on the left. Obviously, you’ve had your own brushes with that. We also just saw The New York Times imposing new rules on its journalists about what they can and can’t Tweet. The reason they gave was that the White House “does not distinguish” between Tweets from individual journalists and Tweets representing the official, institutional opinion of The New York Times. It’s like this whole “when they go low, we go high” thing. So, I was wondering, first, what do you think about that rhetoric of civility, and, second, whether you think it has a place on the left. You know, this idea that we should maintain a staid sense of decorum at all times.

JI: I think there are two issues. One is the larger question of civility, and yes, we should maintain that because the second you devolve into emotional, ad hominem stuff, the important stuff just doesn't get across and everybody shuts down. Everybody gets their backs up and none of the important issues even get talked about, let alone solved. As for these social media policy guidelines that you see publications and newsrooms implementing — it's tough, because it's an evolving thing. It's everybody trying to deal with the dangers of Twitter and Facebook, but I do think that if we were in a Clinton presidency we would not be having those discussions. We wouldn't have those guidelines.

I do think some of those guidelines are useful because when Twitter first got popular, like in 2009-2010, journalists were encouraged by their editors to get online and Tweet and promote their stuff on Facebook and build a persona — it was a very different animal then. It was more marginal. And now it's become so central — in part because of who the President is — so central to the discourse that they’re right to say that it’s “hard to distinguish.” All information becomes fungible: a Tweet is an article is a documentary, and it's all the same. So it's important to maintain your journalistic bearings and stick to the facts and not speculate wildly or say irresponsible things.

On the other hand, I think part of what’s driving this is definitely the fear of losing access to the Trump White House. And to me, that is extremely worrying. You talk to any Russian journalist, and they're like, “This is how it started for us.” You know, “Access is a poison pill, don't take it.” Because there's always a trade-off. If you want access, you have to play nice. This has long plagued the Washington press corps, even before Trump. You make certain trade-offs for access, with every administration. You play nice, you don't publish certain things, you aren't overly critical, because you want that official or the President to sit down with you again.

MV: It’s a relationship.

JI: It’s a relationship, but the question is, how much do you get from that access? Are you giving up more than you're getting? I think with this President the problem has become much more acute and the trade-off has become far more lopsided. Because it's not like — just from personal experience — it's not like they talk to you any less if you're less critical. This is a media-obsessed administration and they’re obviously more likely to talk to you if you're a friendly publication, but you're never going to be truly friendly if you're the New York Times or The Atlantic or Politico. You're never going to be Breitbart or, like, Mike Cernovich.

MV: Right, so I guess the question is, what is there to be gained from civility — just access?

JI: It's access, but also, I think there's a compelling argument to be made that it's your standing, and the trust people put in you. Readers think that you’re an objective source of information, an objective arbiter and analyst of information. I had a conversation about this with Tucker Carlson before the election. I don't agree with him on much, but he actually made a really good point — that all these journalists write these very balanced stories and they bend over backwards to try to be objective, but then they're also on Twitter spouting off their personal opinions, which undermines the very premise of objectivity. I think there's a lot tied up in that and there's a reason it's being so fervently discussed in newsrooms.

MV: It seems like this administration is more likely to respond to media affronts than to any other kind of stimulus, so you maybe want to be careful that you don't jeopardize your access.

JI: But then again, access can entrap you. Access can be a poison pill. And then there's also the business side of things, and advertising. I think there's a concern on the business side of newsrooms that if you become too vehemently anti-Trump you become so unappealing, or you become so radioactive for advertisers that you just end up going under. And then none of your excellent journalism gets published.

MV: So access to the public is part of it, too.

JI: Yeah, it's a really fraught, uncomfortable discussion and I don't think it would be happening if there were a Clinton presidency, but here we are.

MV: OK, next question, piggybacking off of that. How do you personally deal with trolls? Have you found an effective strategy, and if so, what is it?

JI: Because I have a verified account on Twitter, I have that blue checkmark — I have the option of only seeing verified responses, and most of the trolls don't have blue checkmarks. I just don't even know most of it is happening. People will say, like, “Oh my God, have you seen what’s happening?” And I’m, like, “Nope, sorry, don’t care.”

MV: Well, that’s probably better for sanity and peace of mind.

JI: But as we’ve seen from this election, a lot of times it's not random. Or, it starts off random, but very quickly a mob with pitchforks gathers on Twitter and starts hounding you. And I think that's another thing that newsrooms are starting to deal with, which is, how do we protect our journalists from online harassment? And it turns out that’s very difficult to do, because our laws have not kept up with the technology. I've called the police at least twice because of threats I was receiving online and there wasn't really anything they could do. Because even if you get through the VPNs and you got the real IP address, and you find the actual computer from which the threatening message was sent, it’s very hard to prove that a given person was sitting on the computer at that moment pressing “send.”

MV: It seems like the legal framework just isn't there to prosecute in any meaningful way.

JI: It's not, yeah.

MV: OK, so now, a more general question: has your coverage of Russia changed since the 2016 election — either in the types of things you cover or the way you approach them?

JI: It has, but mostly because I'm based here. I'm based in the States. I'm in Russia maybe once a year and it's hard to write about Russia from here. And I don't really want to be writing about Russia. I don’t think Russia is the most interesting thing going on right now. I think we’re at such an interesting political moment in the US — I want to be writing about that! But because I have experience in Russia I'm constantly asked to weigh in on it.

MV: It’s a cycle.

JI: It’s hard to break out of it. But it’s made me a lot more cautious, so I've actually been writing a lot less. I’ve been a lot less prolific because I just want to make absolutely sure that I'm not speculating. I see so much written about Russia by journalists who have never been to Russia, never studied Russia, who don't know anything about the place, and I see how wrong they get it a lot of the time — not because they’re trying to, not because they’re not smart or good journalists, but just because they don’t have that experience or that knowledge base. And I don't want to spend my time debunking fellow journalists. It's just not a good use of my time. And it's very frustrating.

MV: We saw just now how that plays out — basically that very thing, where someone asks you a question that is not super relevant and, yes, you could debunk it, but that wastes a lot of time.

JI: Well, I've written some pieces, but I think my frustration is that we're not talking about Russia. It’s one of those, “what we talk about when we talk about Russia.” We're actually talking about the US. And it’s a domestic story, it's not so much a Russia story. So whenever I try to explain, and maybe I'm not doing it well, maybe the story’s not well-written, or I haven’t found a compelling way to get this information or analysis across… But I find that when I start getting into anything that is actually about Russia, like, their banking system unravelling or another journalist getting attacked or something — I see it in the way people interact with Tweets. It’s just…you know, crickets.

But the more inflammatory and crazy it is, the better. And the echo chamber picks it up. You write a crazy story about how, basically, Putin called Trump and said “You do this,” and you get invited on all the TV shows and everybody picks up your story and it gets massive coverage and play. But if you write, “Well, actually, it's a little bit more complicated, and we don't really know a lot of things yet, and this person who you say was very important is actually a lot less important, and more of clown than a sinister villain” — crickets.

It's very useful for Americans to have a foil for themselves, because, again, we're talking about ourselves. We're not talking about Russia. Especially for liberals, especially for Democrats, it makes it so much easier to understand what happened in 2016 if somebody else did this to us. As opposed to: We did this to ourselves, as a society. And that’s a very Russian response. And that's what I find deeply, deeply frustrating.

The atmosphere has calmed down a little bit now, but for a while it reminded me of the atmosphere I saw in Moscow in 2012, or in 2014, where there was such anti-American sentiment and paranoia. Anybody who took a trip to the US was suspect, anybody who worked for American organization was suspect, anybody who had American friends was suspect, every organization that had an office in the US was suspect and was responsible for the protests or for the Maidan. And it’s just ludicrous, it completely devalues the role that local actors play. And that's straight out of Putin's playbook, we're just doing it for him.

MV: I wonder what you think about the way that conspiracy theory has become such a huge and attractive thing for so many people. I remember hearing that one conspiracy theory about Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, that it was full of dead people from the start. At the time, I was like, who could believe this?

JI: Sometimes the conspiracy theory, or some version of the conspiracy theory, ends up being true, but never in the way you think. So, for example, this excellent film just came out called Icarus. It’s this guy, an amateur cyclist, and he decides to show how easy it is to get away with doping — by doping himself. And he has a Russian scientist, who is actually the director of the WADA [World Anti-Doping Agency] Lab in Moscow, coach him on how to dope and how to evade detection. And the story takes a massive left turn. I don’t know if you remember this story, The New York Times published it, about how the FSB and the Russian government had this very elaborate system for swapping out dirty urine during the Sochi Olympics, because all the athletes there were doping actively, and in the middle of the night they were switching out dirty urine samples for clean ones through a hole in the wall. And the documentary shows it happening, because the guy defects and basically becomes the whistleblower Sherpa and says, “Here’s how we did it.” And even when he says it and it’s proven, you think, that’s so insane and unbelievable. But it happened, and nobody could have predicted it. And even when presented with the evidence, a lot of people didn’t believe it.

What you need is something we don’t have yet in the case of the election, and might never have, which is somebody from the inside saying, “Here’s how we did it.” And once they do, it’s going to be surprising. It won’t be the way that we predicted. Because truth is stranger than fiction.