Emily Wang is Assistant Professor of Russian at the University of Notre Dame and is currently writing a book provisionally titled Civic Sentimentalism: Pushkin and the Decembrists. Her personal website is http://www.emilyambrosewang.com.

Alexander Pushkin died in 1837 and does not personally maintain a web presence.

“It is difficult, though possible, to read all the books that Pushkin read. But it is much harder to forget (even briefly) all the books that Pushkin did not read but that we have read. When we open up a classic, we avoid asking ourselves the most basic question—for whom was this book written?—because we know the most basic answer: not for us.”

М. L. Gasparov, “The Ethics of Philology” (trans. Michael Wachtel, from “On Bakhtin, Philosophy, and Philology: Two Essays,” PMLA 130(1): 2015, 137)

“How would Pushkin behave if he lived a half-century later, when Russian capitalism began to eat away at the body of the people alongside the still-living landed aristocracy? Pushkin would not lose spirit, he would divine the nature of this new period in history and would not have fallen for the temptation of sorrow. He would have remained Pushkin and would have still penetrated into the secret recesses of the people, where the progressive, happy energy of living development is preserved and carries out its activity, even if these recesses were even more remote. […] Pushkin would not have left us common people behind.”

Andrei Platonov, “Pushkin and Gorky” (trans. Jason Cieply, forthcoming in Pushkin Review 20)

I. Itkin, “Litseisty na progulke,” I. Itkin, from Rodina: Istoricheskii naucho-popularnyi zhurnal

Pushkinists know that today is a holiday. The first graduating class of the Tsarkoe Selo Lyceum annually celebrated the anniversary of their first day of school by gathering, drinking, and reminiscing. In its early years, this holiday was suffused with the “Lyceum Spirit” (litseiskii dukh) that earned the graduates a reputation for libertinism and went on to become a watch-word for the secret police. Many of the verses that Lycean poets wrote to and about one another were filled with inside jokes about drinking and flirting, engaging in what Joe Peschio calls “the poetics of impudence and intimacy.” In one infamous epigram, Alexander Pushkin transformed the last name of his friend Wilhelm Küchelbecher – then an awkwardly sincere young poet of German descent, later a Decembrist who joined the secret society only two weeks before the Senate Square uprising – into a synonym for social awkwardness:

За ужином объелся я,

А Яков запер дверь оплошно —

Так было мне, мои друзья,

И кюхельбекерно и тошно.

“Litseitsty u okna bulochnoi,” from the student journal “Litseiskii mudrets,” 1815, published in Rodina: Istoricheskii naucho-popularnyi zhurnal

The reunion itself was the most important part of that holiday. When Pushkin was unable to attend these events, his acute awareness of his friends’ absence inspired some of his most celebrated poetry – and quite a different perspective on friends like Küchelbecher and his fellow Decembrist Ivan Pushchin:

Чем чаще празднует лицей

Свою святую годовщину,

Тем робче старый круг друзей

В семью стесняется едину,

Тем реже он; тем праздник наш

В своем веселии мрачнее;

Тем глуше звон заздравных чаш

И наши песни тем грустнее.

In 1830, during the famously productive “Boldino Autumn,” when a cholera epidemic trapped Pushkin in a provincial town for three months, the poet marked the Lyceum Day holiday by burning his draft of the tenth chapter of Eugene Onegin. This chapter – which scholars have partially reconstructed by deciphering encrypted fragments – explicitly depicted a St. Petersburg secret society, and included ironic portraits of several friends.

These relationships with friends and contemporaries helped define Pushkin. Some of his works are incomprehensible outside of that context. M. L. Gasparov reminds us that Pushkin often wrote specifically for these individuals.

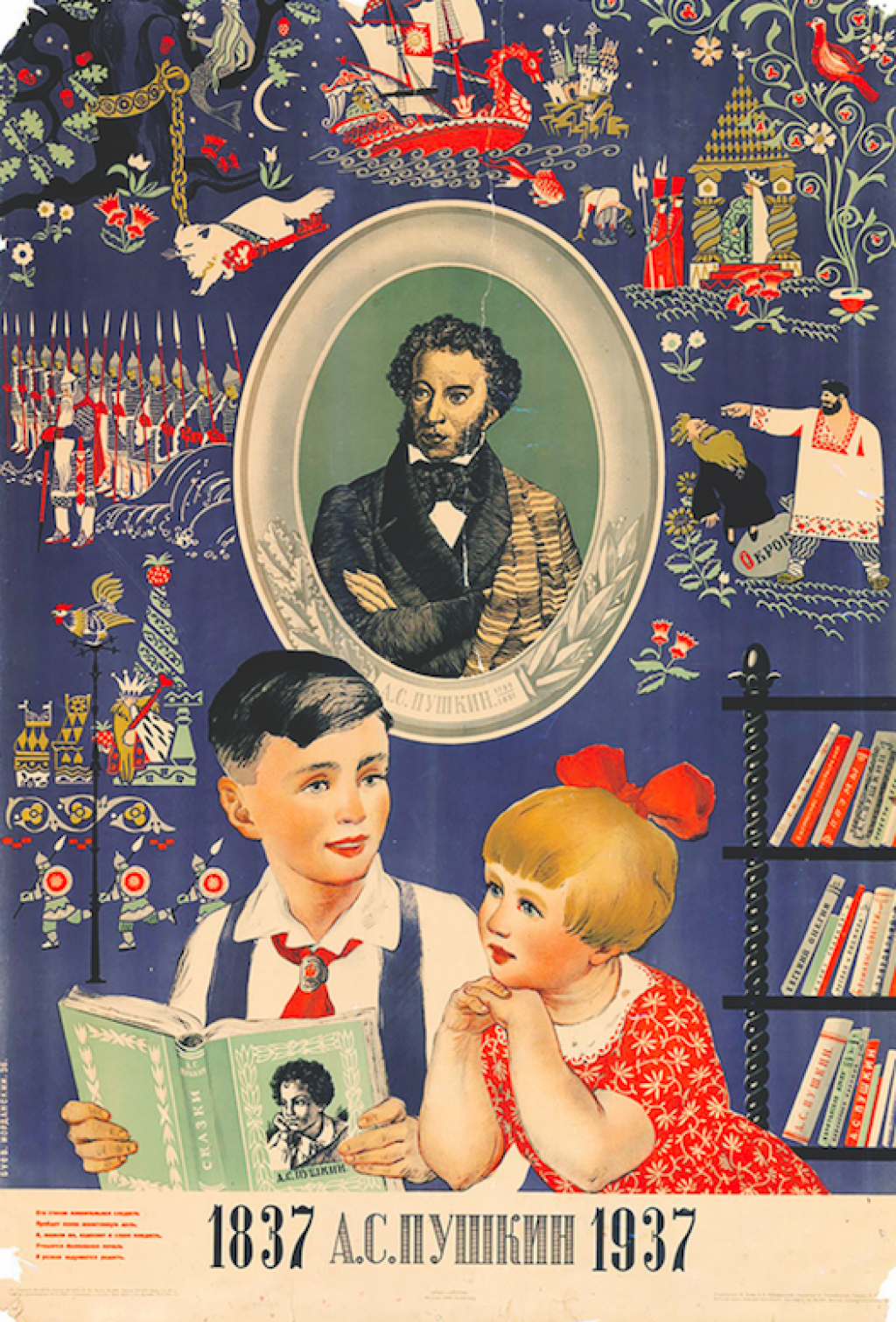

Yet, to evoke Marina Tsvetaeva, all modern readers seem to have their own versions of Pushkin. This tradition was perhaps codified by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1880 speech commemorating the unveiling of Moscow’s Pushkin monument, which used examples from Pushkin to advance Dostoevsky’s own messianic vision of the Russian writer’s role in society. Indeed, during much of the nineteenth century, radicals regarded Pushkin as backwards, if not reactionary; we recall the scene from Fathers and Sons in which Arkady Kirsanov gently removes a collection of Pushkin’s poetry from his father’s hands. After 1917, Jonathan Platt recounts, leftist thinkers actually continued to regard Pushkin as an out-of-touch aristocrat until the 1937 Centennial Celebration of the poet’s tragic demise, when he and the Decembrists became indispensable precursors to the Bolshevik Revolution (Greetings, Pushkin! Stalinist Cultural Politics and the National Bard, 2016).

Pushkin jubilee image from Zhivaia istoriia.

The forthcoming issue of Pushkin Review offers us glimpses into several versions of Pushkin that developed during the Soviet Union. In a cluster of translations titled “Pushkin Is Our Comrade: Mikhail Lifshitz and Andrei Platonov on the Legacy of Russia's Classic Writer in the Soviet 1930s,” Ania Aizman, Jason Cieply, and Pavel Khazanov translate three articles by two unorthodox Marxist thinkers, alongside scholarly introductions from Cieply and Khazanov. Mikhail Lifshitz defends the mature Pushkin’s conservative aristocratic outlook – which other Stalin-era scholars denied – as, paradoxically, revolutionary in and of itself. Meanwhile, Andrei Platonov, who belonged to the same literary circle, argued that Pushkin’s genius had miraculously distilled the essence of life normally understood only to Russia’s most dispossessed, and that his poetry not only embodied the people’s will but – by inspiring readers – helped his country move towards communism.

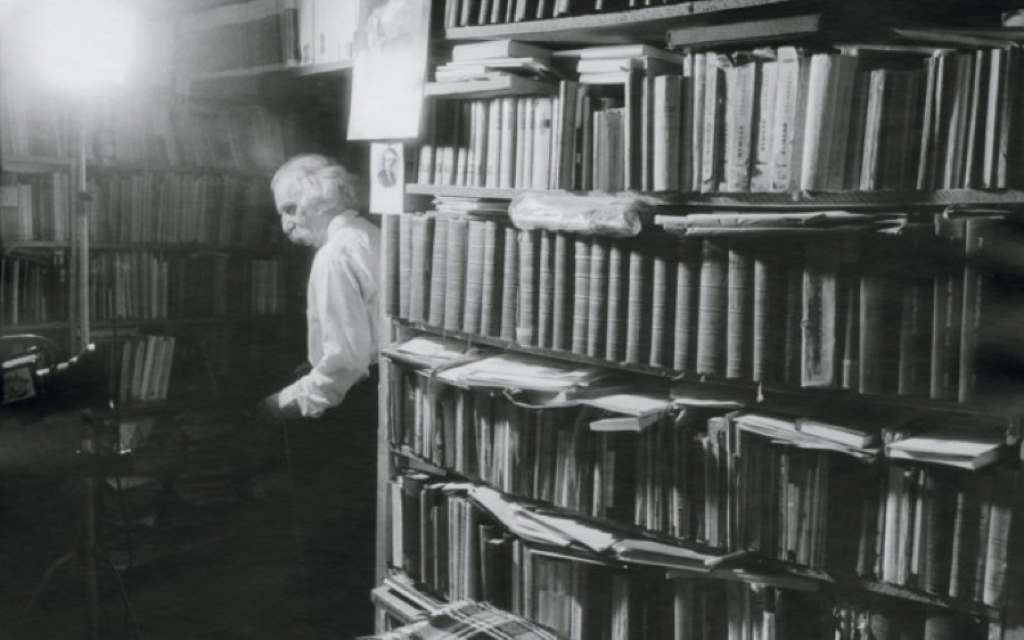

Yuri Lotman during the shooting of the series “Besedy o russkoi kul’ture,” late 1980s. Photo from the ERR archives.

Another cluster of translations, “From the Archives of Pushkin Scholarship: Three Essays,” edited and introduced by Michael Wachtel, offers several important works of literary criticism in English for the first time. Though the philologists Mark Azadovsky, M. L. Gasparov, and Yuri Lotman also emerged from the Soviet Union, they represent a completely different scholarly tendency. Azadovsky’s article, translated by James McGavran, quietly overturns Soviet dogma by demonstrating that Pushkin’s fairy tales derived not from an indigenous Russian oral tradition – according to legend, the source was his nanny Arina Rodionovna – but rather from Western European models. Lotman’s piece, translated by Laura E. Christians, reconstructs an early nineteenth-century Russian nobleman’s understanding of the duel, without which neither Eugene Onegin, nor Pushkin’s own biography make much sense. Finally, Wachtel translates a piece from Gasparov that considers the significance of a particular poetic meter – here, trochaic tetrameter – across not only Pushkin’s oeuvre, but even throughout the entire Russian poetic tradition.

Finally, an article from Geoff Cebula shows that although their Futurist forebears called for him to be thrown “off the ship of modernity,” OBERIU poets were not immune to the temptation of seriously evoking the classic poet in their own writings. He analyzes Alexander Vvedensky’s stark meditations on death, which return to a theme that deeply preoccupied Pushkin personally (recall the Lyceum poems) and went on to dominate his role in cultural memory, when he perished at the age of 37. Yet Vvedensky does not conflate his position with Pushkin’s; his friend Lipavsky recalls that the he said, “I’ve understood how I am different from past writers, and indeed from people in general. They said: life is a moment in comparison to eternity. I say: it is a moment overall, even in comparison to a moment.”

Though this issue of Pushkin Review shows several visions of Pushkin that emerged from the Soviet Union, the protean poet continues to present problems and opportunities. Official and unofficial versions of Pushkin still proliferate, especially in Russia. 2007 saw a murder mystery film set at the Tsarskoe Selo Lyceum titled 1814. Just a few years later, a computer game inspired by Eugene Onegin – but with fellow nineteenth-century literary heroes Alexander Chatsky and Evgeny Bazarov, plus vampires – paired pre-revolutionary orthography with anime-inspired illustrations. In 2015, the official “Year of Literature” logo featured Pushkin’s famous profile alongside Anna Akhmatova and Nikolai Gogol’, rendered in the colors of the Russian flag. The updated site uses the same logo with the current year. (It is unclear whether the fact that all three writers famously celebrated their non-Russian heritage was an intentional symbol of the ruling United Russia party’s current vision of multinational imperialism or not.) And, like Platonov, artists and thinkers continue to imagine what Pushkin would be like today. In a recent series of illustrations, the artist Aleksei Sergienko depicts the Pushkin skateboarding outside Catherine’s palace, receiving an award from President Putin, and making a talk-show appearance barefoot, with an Apple-like laptop branded with a red star.

Painting Aleksei Sergienko, from Moiarossiia.

We’ll never unread all those books Pushkin never read, but we do continue to read – or at least to talk about – Pushkin. As in the past, he continues to offer insight into contemporary concerns – and sometimes to push us in new directions.

The Pushkin Review is a peer-reviewed annual journal published by the International Pushkin Society. Those interested in receiving Pushkin Review may write to Editor Emily Wang (ewang3@nd.edu) and Treasurer Timothy Portice (tportice@middlebury.edu). Annual dues for the International Pushkin Society are $30, and come with a subscription to the journal. Libraries may subscribe by contacting Slavica Publishers (slavica@indiana.edu). Back issues are available in print from Slavica and online through Project Muse (https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/532) and at http://www.pushkiniana.org, maintained by Web Editor Ivan Eubanks (ieubanks@ucci.eu.ky).

For article or translation submissions, write to Editor Emily Wang (ewang3@nd.edu). For book reviews, write to Book Review Editor Katya Hokanson (hokanson@uoregon.edu).