Joan Neuberger is Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the editor of Not Even Past, the blog on which this post originally appeared.

As historians, most of the time we tell stories about strangers. But I come from a family of story-tellers and, in our family, Passover was a special occasion for telling family stories. So, today I’m writing a story about a beloved family photograph.

This photograph is famous in our family. It shows the Passover seder that took place when the Rittenberg family met at my great-grandfather Louis Rittenberg’s apartment at 525 West End Ave in 1934. A professional photographer was hired for the occasion (judging by the light along the upper right wall). We think that Louis’ daughter, Bea, bought the gray Hagadahs that we used for many years afterwards for the seder this evening.

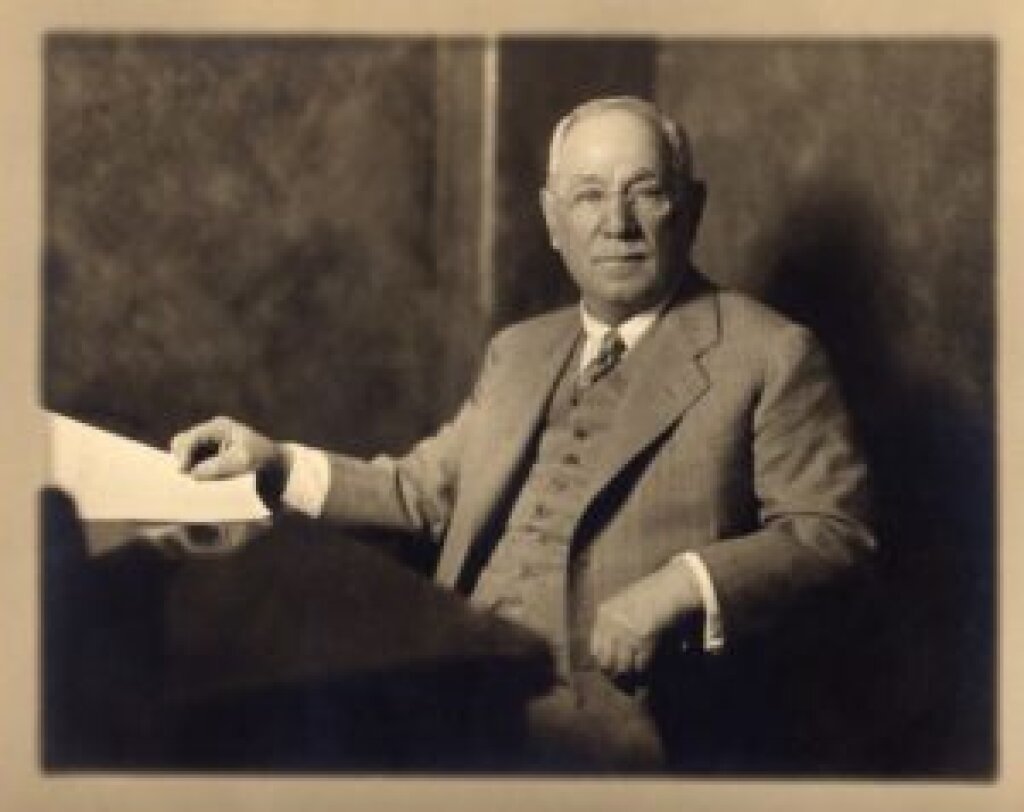

Louis (at the far end of the table on the right) was born in Lithuania in 1861 (or 62) and emigrated to Massachusetts as a teenager with his father Wolf in 1878. They supported themselves peddling brooms and novelties. Wolf was described as “refined” but not “practical,” (I imagine him a dreamy, scholarly rabbi’s son, happier reading than selling brooms). He returned to Lithuania, leaving his wife, “Mutter,” and son Louis, who made enough money peddling to open a store that sold dry goods and peddling supplies in Springfield in 1887. Louis married Lillie Marks in 1884 and, when children began to arrive, they moved, first to a two-family house and later to their own house, described very proudly years later by his oldest son, (and our first family historian), my great-uncle, Newman Rittenberg.

Louis founded a synagogue in Springfield, became President of the “Sons of Benjamin,” and joined the Masons. As his business grew, he helped bring over, support, and educate family members from Lithuania and other Jews struggling to get started in and around Springfield. On Sunday mornings, Jews from all over came to Louis’ “open house” for advice. His first store failed but Louis was remarkably ambitious and benefited from the growing regional textile industry. One day, when he was looking around a storehouse in nearby Holyoke, he learned that he could buy the cloth left over from making suits in New England and sell it to manufacturers making caps in New York. It would take a while, but this discovery, and the middle-man “jobbing” business it generated, would make him rich. In 1908 Louis moved the family to the Bronx and went to work on Canal St in Manhattan where his brother Ike had a similar business. Louis continued to buy and sell cloth, prospering and suffering with the ups and downs of the economy. In the 1910s, the business took off for good and the Rittenberg brothers were soon supplying many of the largest clothing manufacturers in the country with cloth they purchased from New England mills. In around 1912, the family moved to Central Park West and then, after Lillie died (far too young), they moved to the apartment on West End Ave. Louis’ distrust of the stock market meant that they survived the 1929 crash far better than most.

The family histories that recorded these stories leave out the social and political context that made it possible for a young, determined, white man from eastern Europe to succeed here, but Louis and Lillie were universally described as generous and principled and cultured and funny. Louis was famous for saying things like “Kind words never hurt anybody.” And: “There are 112 million people in this country and they all have to wear clothes.”

Uncle Newman reports that the extended family gathered every Friday night and, of course, every year on Passover. Newman described Louis’ religious sensibility this way: “He was very learned in Hebrew but departed from the very strict rituals, as he felt that the modern times should alter the strictness of the old customs. He approached his religion most seriously but with a knowledge of the American condition…”

At the far end of the table in the Passover photograph, you can see the top of the silver wine cup stand (poking up between Louis and my grandfather, Willie). The children in the picture include my mother, Lillian (named after Lillie), her sister Ann and their first cousins, Joan, Peggy, and Lynn Gross, and Bob and Ann Bry. When I was growing up, we used the same wine cups and and same Hagadahs every year when Joan’s and Lynn’s families came to our house for seder. My sister Lois and I polished the antique silver wine cups each year and set the table with the same hagadahs, rituals we always enjoyed. Now the silver cups live with us in Austin. I wish we knew more about their history, but you can see them in action here when our own kids were still living at home.

The family photograph itself often provided an occasion for my mother, who seemed to know something about everyone in every generation of the family, to tell us stories about growing up in New York surrounded by our interesting relatives. But mostly we liked looking at it for that uncanny sensation of the past in the present — seeing everyone in our parents’ generation as children.

This week, Joan, Peggy, and Lynn gathered for seder with their families at Lynn’s house in Mamaroneck, NY. Lynn’s son Phil Straus, a wonderful photographer, recreated the photograph with their own children and grandchildren and even a few great grandchildren.

Photos and stories connect us with people, whether we knew them or not.

From generation to generation….

For more stories from my family archive: Braided History and Fathers and Sons.

On the Jews of Springfield: James Gelin, Starting Over: Formation of the Jewish Community of Springfield, Massachusetts, 1840-1905