* Today's post is the first in what I hope will be a series in a new category of blog posts: Pedagogical Field Notes, in which we discuss issues related to the Russian classroom. As always, I welcome (and plead for) submissions.

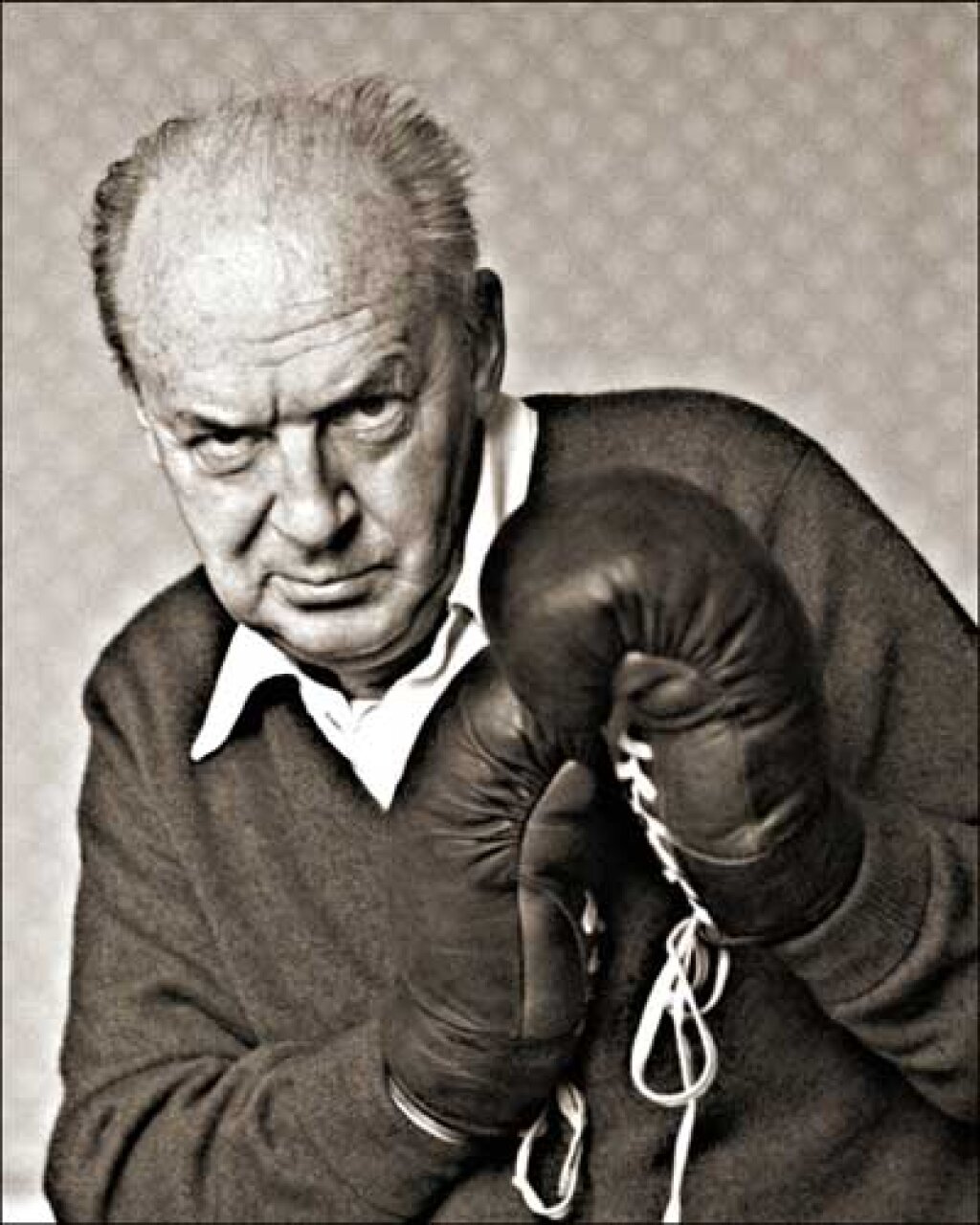

Forget Reading Lolita in Tehran--the strangest place I found myself reading Nabokov was in a Russian literature class.

Nabokov has always been one of those Russian cultural products on which Russia's could have only a partial claim. His English novels have the aura of sex and scandal about them, while his Russian works bear the burden of high context. A "love affair with the English language" (Lolita) is a much easier sell than a life-long contempt for Chernyshevsky (The Gift).

In the old days, Nabokov existed in his own curricular world (more than appropriate for an author whose heroes create their own universes as a matter of course). Soviet Literature surveys excluded him for the obvious reasons, while Nabokov's vast body of work made him virtually the only twentieth-century Russian writer who could justify a single-author course (taught, often as not, in English departments). With the USSR no longer a going concern, the rationale for keeping Nabokov out of surveys is long gone, though his ability to sustain a monograph course is unabated.

All of this means that, as a specialist in 20th century Russian literature and culture, I've spent two decades doing everything I can to avoid teaching him. I've brought in guest lecturers, fobbed off the 20th century survey on colleagues, and, most shamelessly, included Nabokov on a syllabus, only to fall mysteriously ill on the day we're supposed to read him (Nabokov seems to bring out the Gogol in me) All of this because, as I recently admitted in a desperate Facebook S.O.S., I really can't stand Nabokov. I have no problem with Chapaev or Cement, but wouldn't go anywhere near Glory without hazard pay.

Setting aside my personal impatience with ornate, slow-moving prose, I think the problem is one of context. Or, rather, the lack of context: I never know where to put him. This is particularly ironic, since the last decade has seen a remarkable determination to create new and jarring contexts for Nabokov. Azar Nafisi sees him as an apostle of liberation--reading Lolita will set you free! Nina Khrushcheva transforms Nabokov into a champion of individualism, self-sufficiency, and entrepreneurship--an Ayn Rand hero, but with better prose (shades of The Gift!). How strange that Nabokov, who doesn't want to be interpreted at all, who equips all the English language editions of his books with prefaces warning the reader not to take things the wrong way, provides the grist for so many different ideological mills. And how appropriate that the best Nabokov criticism I've ever read is Eric Naiman's aptly-titled Nabokov, Perversely.

"Perversely" is really the only way I can treat Nabokov, so I sandwiched him between two of the least congenial neighbors I could imagine for him: Socialist Realism and Andrei Platonov. This, in turn, helped me highlight the weirdness of reading Nabokov as part of Russia's twentieth-century "literary process." They read Invitation to a Beheading, completed a writing assignment that was due before class began, and ended up spending half an hour talking about the preface. With the bar safely lowered, I can declare this class a success.

Now I just need someone to give me permission never to teach Nabokov again.