Yelena Furman teaches in the Department of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Languages and Cultures at UCLA and writes on Russian-American fiction.

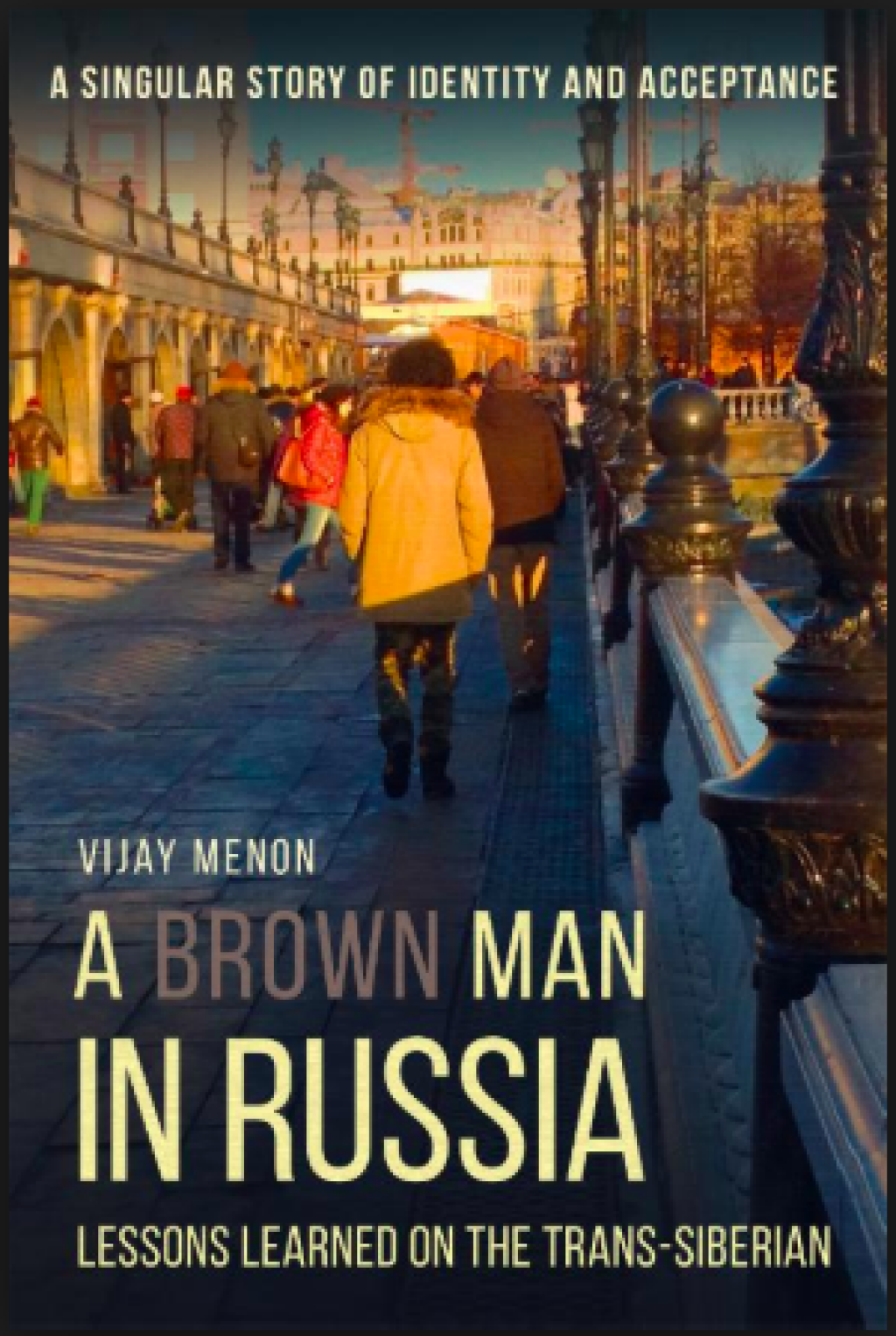

When he was five years old, Vijay Menon got a National Geographic Atlas rather than a coveted Nintendo game from his parents for Christmas. Although this convinced him that “Santa Claus was dead,” the gift proved invaluable by spurring a deep love of travel: as he says, “you only get one life and it’s way too short to spend in just one place.” Securing cheap flights via the Internet, he had taken more trips abroad by the time he was in college than many people do in their lifetimes. In 2013, the twenty-year-old Duke undergraduate took one such trip for reasons that he admits remain somewhat murky but that have to do with a rather inexplicable wish for a “Mongolian Christmas”: with two of his college friends, Menon embarked on a train journey on the Trans-Siberian from Russia to Mongolia. He subsequently gave a TEDx talk about this trip and later turned it into a book, complete with photographs of the journey: A Brown Man in Russia: Lessons Learned on the Trans-Siberian (London: Glagoslav Publications, 2018).

As befits a travelogue, the book describes the places visited, which in this case include both the traditional tourist destinations of Moscow and St. Petersburg, but also more unusually, cities on the Trans-Siberian path: Tyumen, Irkutsk, and the Mongolian capital, Ulan Bator. Readers discover, for example, that Tyumen’s main sight is the giant “Lover’s Bridge,” while fashion in Ulan Bator is “flashy, colorful, ostentations, and hip – matching its surroundings.” More than travel vignettes, however, the book is a paean to the author’s desire to see the world. With straightforward but engaging prose, including in the occasional explanatory footnotes, Menon brings his readers along for the often alcohol-soaked ride, imparting his observations with the humor that is a necessity for travellers dealing with unfamiliar surroundings and a lack of relevant language skills.

A large part of the comic overlay comes from his own lackadaisical attitude to travel. He admits to being one of those travellers who rather than plan ahead prefer to spontaneously figure things out as they go along. Predictably, this method fails him in Moscow, where he cannot read Cyrillic, has trouble navigating the vast metro system, and is generally disoriented in a city not known for its friendliness. Reader reaction includes some bemused eye rolls at the ways in which he attempts to deal with his lack of preparation, such as deciding that, since one of the metro passengers looks “like a city slicker,” he is going in the right direction toward his hostel in the city center.

At the same time, this book is enjoyable largely for the way in which these absurd levels of unpreparedness actually pay off. By sheer coincidence, he gets on the right metro and finds his hostel and friends; firmly yelling “Nyet!” – one of the few Russian words he knows – to train station employees who shuffle him back and forth between ticket counters, he succeeds in purchasing the elusive tickets; lacking all familiarity with Russian train stations, the travellers almost miss getting on the Trans-Siberian, but manage to find it at the last minute. While such a carefree attitude may not convince those who meticulously plan their itineraries, the book is a reminder that how you get there is ultimately less important than the fact of your getting there in the first place.

However, as its title suggests, A Brown Man in Russia: Lessons Learned on the Trans-Siberian is more than a catalogue of travel (mis)adventures by an often underprepared but sincerely curious millennial. Menon is first generation Indian American, and the lessons he learns, imparted via a “Lesson” subsection in each chapter, are meditations on cultural identity, alienation, and belonging in both Russia and the U.S. The book’s uniqueness stems from being written by a brown American traveller in Russia, a point of view not traditionally represented in travel or other types of literature, with Menon’s ruminations on his cultural position forming the backbone of the travelogue.

Racism and xenophobia in today’s Russia stem from a long history of Othering those not ethnically Russian, as well as the whipping up of nationalist rhetoric in the post-Soviet era. Some of what Menon experiences fits into this picture. On his first night in Moscow, he is stopped by a police officer for some raucous late-night behavior, saved from any severe consequences only after his white friend intercedes on his behalf. In response to his request to use the bathroom in the Petersburg hostel lobby, the front desk clerk asks him if he is “a criminal.” Such incidents are of course not limited to Russia, and Menon infuses his discussion with forays into racism in America. Laudably, he organically weaves discussions of institutionalized race and gender inequality into his narrative alongside descriptions of sightseeing and visits to various food and drinking establishments.

However, A Brown Man in Russia undercuts reader expectations: the surprising thing about this book is that it presents Russia as much more racially tolerant than Western readers might expect. As Menon says, “there were minor occasions of nativism or racism. But they were so wholly overshadowed by the genuine goodness of the people who showed unabashed curiosity towards our stories and who backed it up with boundless displays of goodwill towards us.” The bulk of the chapters focuses on the bonds Menon and his friends forge with the other passengers on the Trans-Siberian through drinking, playing chess, teaching English, and exchanging stories of life in Russia and America. This contact results in one of the most significant lessons about the two-way street of cultural belonging. As he says, “I recognized that I need to overcome my own insecurities to reject the notion that ‘I don’t belong.’ And I also realized that it is the responsibility of those around me to help make me believe it, too.” Initially feeling “out of place” in Russia and lacking Russian language skills, he challenges himself to communicate with and try to learn about the people around him. Many respond in kind, prompting both sides to connect over common interests, or learn something new, or change opinions, leading to mutual acceptance. By the end of his trip, Menon may be a foreigner in Russia, but he does not feel, nor is he made to feel, like an Other.

The book is not without its drawbacks, one of which is that Menon could delve deeper into the weighty issues he raises. And given his awareness of gender inequality, it seems curious not to acknowledge that the very fact of being able to take a long train ride in a foreign country with mostly male passengers would be much more problematic for women due to a patriarchal system in which female bodies are targets of violation. Nevertheless, the book is a unique addition to travel writing and writing about Russia and would make a good reading recommendation for students of color, and anyone else, going to Russia. At a time of heightened tensions between Russia and the U.S. and the myriad occurrences of racism in both countries, A Brown Man in Russia: Lessons Learned on the Trans-Siberian serves as a poignant reminder of the need to challenge preconceptions, both others’ and our own, and of travel’s vital role in bridging the differences between us.