Liza Ivanov is a teacher who recently graduated from New York University.

When I tell my story of immigration, which story do I tell?

My great grandfather’s? An 18-year-old Ivan, only a light fuzz on his chin, looking out of the window of the Emperor’s Naval Academy that autumn day in 1917, revolution rolling down his street. Firing a few shots for the valiant present--the tsar, the empire--that’s now so unbelievably the past. Standing by the door as the kitchens are looted and the director arrested.

Ivan was then smuggled to Vladivostok—still a ‘loyal’ city—with his academy. There, amid the chaos of colliding empires, they still learned their lessons every day. Three years later, one starless night, Ivan was woken. We’re leaving, they're coming. The academy, students and professors, left the port that frozen night to board The Eagle. “Just another training?” the untested cadets asked hopefully. The ship is sinking! someone screamed—the Kingston valves had been unscrewed. It’s the secret Soviet agents...we knew that they’re everywhere, all the time, invisible. The mechanics, cursing, plunged into the oily frozen waiter to screw on new ones. As the Eagle left the port, a Soviet battery rumbled up the shore. It came close, but not quite close enough to fire.

The Tsar’s Naval Academy sailed on through Hong Kong, Nagasaki, Singapore, and later landed in Tunisia, swapping The Eagle for a building from the French colonists—they had to continue reciting their lessons, of course. Five years after the fall of the empire, Ivan graduated as the Emperor's naval officer.

He went to Paris. For the first year, he worked as a dog-sitter for a French aristocrat. When the Austrian princess came to dine, Ivan was invited to the table. Although his noble blood was respected, Ivan quit before the year ended: service life was too degrading for a Russian with a coat of arms from the tsar. Life in Paris became a 15-year cycle of taxi driving and roaming bars with the other Russian emigres with the same strange lost hysteria in their eyes. Each night they planned new crusades to free Russia from the Soviets. For a few nights, drowning in wine-drunk machinations, Hitler seemed like the man. Chto? At least he would oust the monstrous Soviet evil, and they could return as heroes, preservers, or without celebrity altogether—the return home would be enough. Before leaving France for America, Ivan burned all the diaries from his Parisian years, leaving only one sentence on a blank page: "lonely, so lonely."

He recited poetry as he sailed into the New York Bay—this would be it, the land at the margin of his dreams. Soon, he met Marie Kelman, a plump German lass with a stately around-the-head braid and an art degree from Hunter College. She set up their first date in the hall of the Astor Hotel on Times Square. This is normal for America, his friend told him; relax. Ivan was still scandalized by the implications of meeting at a hotel, but hopelessly in love. Marie became Masha, “the most beautiful and warmest name for Maria.”

January 7, 1940: “It was late when I brought Masha back home to Flushing. On the way, our car almost flipped over, I wasn’t on my guard, and our right wheels ended up in a ditch. Despite the snow, we made it out safely. Stopping at every red light—kissing often and not noticing that even the green light had passed already.”

Three months later: “I began my family life, after the supplications of a Lutheran Minister, less than 24 hours of honeymoon, three dollars in my pocket, a pregnant wife and jobless.”

Flash forward. Ivan and Marie have two kids. Years make Ivan more Russian, more authoritarian, more Orthodox, his will more inflexible. Every day after school (and sometimes dance, music or scouts), he drills the children with Russian and Law of God lessons. Bedtime at eight, no questions asked. Preferably no candy or soda. Of TV: “I personally do not approve…showing the kids the Hollywood filth, but America is stronger than I am.”

Friends call him “Ivan the Terrible,” suggesting that he let his family be normal, but Ivan shows no sign of succumbing. Before his friends come to dine, he calls them to his office and asks that they speak only Russian at the table, no German or Russian or French. His “please” only slightly softens the order. Only at night, in his diary, he writes feverishly “there are many Americans, whose souls are Italian, German, not to mention the Jewish families, who live here for generations, but retain their cultures…. I’m in despair! On one hand—I must, on the other—I am a despot and hegemon and want everything to be my way. It’s not my way, but the way duty commands. There is nothing above our Russian soul…This is what I wish to create in my family.” And ultimately, Ivan’s words are law.

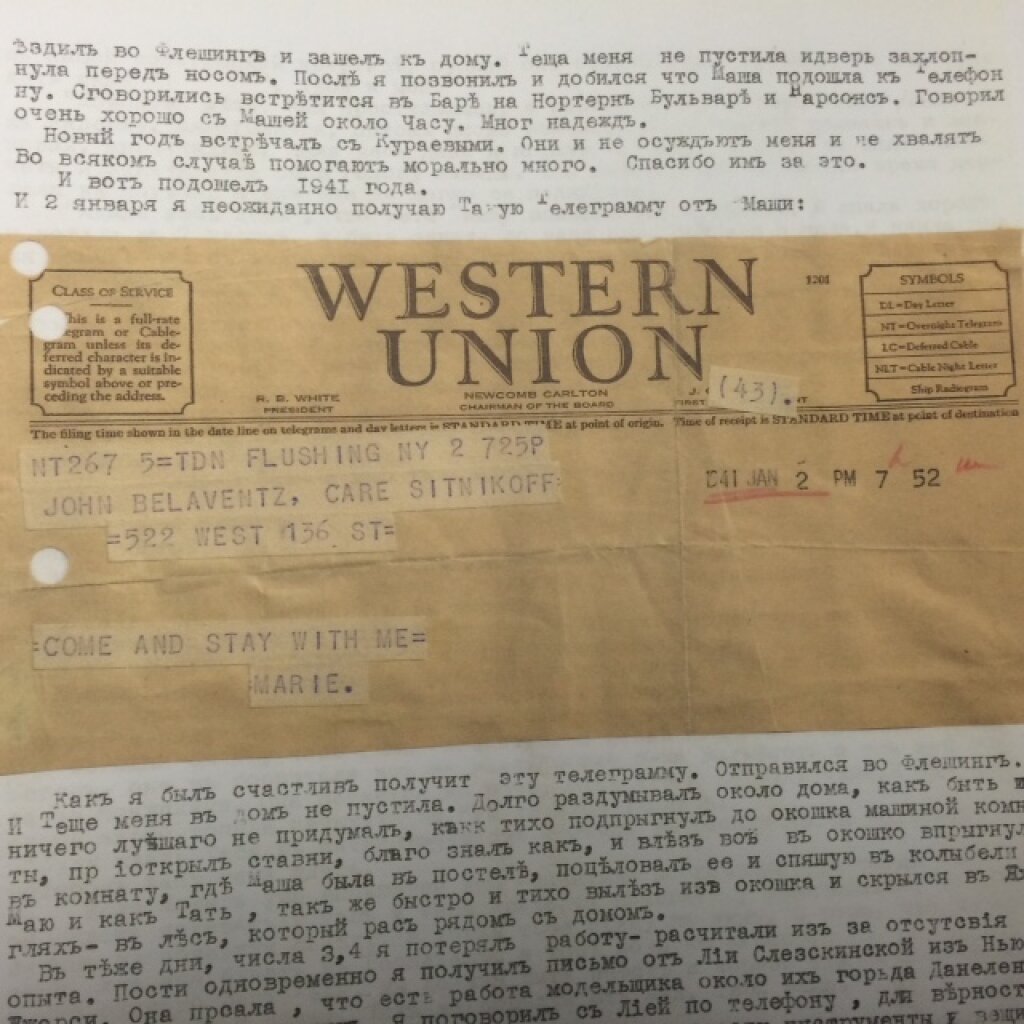

Once, towards the beginning of their marriage, after an argument with his mother-in-law and wife, Ivan left the house. Masha refused to see him for a month. One morning, he received a telegram from Marie: Come. And. Stay. With. Me. Dashing away from his coffee, the 40-year old, balding little man, drove over to his mother-in-law's house, climbed up a tree to his wife’s bedroom, kissed her. Then he leaned over the crib and just stared down at his baby for a long while.

***

Or is my story that baby’s—my grandmother’s—story? Maya, the girl who charmed everyone; a thing of sun and steel. During art lessons, instead of teaching her to draw, the teacher asked her to pose for the class (she was such a “classical” beauty). Maya ended up with a mound of portraits, but never learned to draw. Everywhere she went, all the emigre balls, parties, weddings, she glimmered as first belle of the party, to the great chagrin of her father. At 14, Maya saw Kolya, a young man who had come home from the army. Kolya thought he knew whom he was going to marry (he had a fiancée), but Maya knew better. She lied to him about her age (every following year, she confused how old she was, sometimes adding on two years, sometimes one.) “Maya, I’m not going anywhere,” my Grandpa told her after proposing. 'Can you please tell me how old you are?' She was 17.

Or perhaps Kolya’s, my grandfather’s, story? He was born in the Czech Republic and my imagination has always conjured a single scene (on constant replay) from his childhood; I see him climbing up and down the same chestnut tree, throwing dark plump mahogany nuts on the heads of unsuspecting pedestrians.

When the Red Army approached their town when Kolya was 14, he and his parents boarded the last train leaving for a refugee camp in Germany. They brought along only their family albums, which were stolen that first night. At one of the stops, Kolya's stomach churned and he ran to the outhouse. When he came to the station, the train, along with his parents, were gone. Oh well, he shrugged, and started following the train tracks in what he guessed was right direction. His father—told by his distraught wife that if he came back without her son, he may as well not come back at all—and a few others found him hours later. They say he was whistling as he walked along those tracks.

Or the story of Kolya and Maya's son, my father? One of his schoolteachers, also an emigre, always asked his students to draw a map of Russia on the first day of school from memory. Fifty years later, he would show my father’s map at an exhibition; the boy knew Russia better than the palm of his hand. Brilliant, his teachers said, but what a pain. His parents had hoped he would be another American success story: government job, two kids, house in the suburbs. The religious quirk that runs in my family, though, bounced to the surface when he was 17. Turning down a full scholarship to Cornell, he instead went to a Russian Orthodox Seminary, grew out a beard, and cleaned out the monastery cow stalls before liturgy at five o’clock each morning.

Or is my mama’s, Masha’s story, that of a girl born in Soviet Kazan, the real story? Her parents had multiple Ph.D.’s, so they worked as janitors. What could be more logical during the Soviet Union, when members of the Intelligentsia were glad to have a broom in their hands? Their one-room apartment was a maze of makeshift bookshelf hallways of forbidden literature and they taught their kids to only mouth the Soviet anthem in school. The only way in which the Belgorodskys were good Soviets was that they were atheists until well, Mama's older brother, Leva, came to their mother one morning and said “Mama, I want to be baptized. I had a dream.” She patted his knee, checked his temperature and said maybe. But he came to her again. And again. “Ok, this spring,” she said this third time, hoping that perhaps the deadness of Kazan winters just left too much time for thought. But in February, Leva slipped under a car and died. The whole family was baptized.

After that, years of catacomb reality followed: secret monks sleeping on the couch, forbidden religious literature, six-mile treks in search of the priest in exile. Mama always said my grandmother was prone to forget to cook dinner, but that she would read to her tale after tale; two girl-women, disheveled, hungry, enchanted. Mama, that girl who grew up in the Muslim center of Russia with “Jew” stamped in her passport, hiding her cross from classmates, playing the violin, knew well what could and could not be said outside the house.

At 17, Mama came to the U.S. to nurse an aunt who was dying a slow cancer death. Mama was looking for her jacket on the coat rack at church on East 93rd street in Manhattan, when someone came and pulled on her long, thick black braid, teasing “so this is Masha from Kazan?” When she swerved around, she saw a pudgy boy with dancing eyes. She married him. They had 10 kids.

Or is my story the story of us, 10 Americans with Russian souls? Need I say that we ate borsch, danced gapak, wept Eugene Onegin and dreamt birches. And need I say that we all inherited Ivan’s paranoic distrust—would America give us everything and then steal our souls?