Jennifer Wilson received her PhD from Princeton University in the Fall of 2014. She is currently a Lecturer at the Russian State University for the Humanities (RGGU).

Just this past week, Pussy Riot released their first English language song, “I Can’t Breathe,” the title a reference to the last words of chokehold victim Eric Garner. Pussy Riot posted the song to their YouTube channel on February 18th; in the description beneath the video, they describe the song as an act of solidarity “for Eric [Garner] and for all those from Russia to America and around the globe who suffer from state terror.” While ostensibly a song about police brutality against African-Americans in the United States, the imagery is composed entirely of references to the current conflict in Ukraine. The video consists of Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina being buried alive while wearing Russian riot police uniforms. A pack of cigarettes has been cast off in the dirt that being used to bury them—the brand is “Russian Spring,” a real cigarette label smoked by those who support Russia intervening militarily in eastern Ukraine.

Seeing the use of American racial dynamics to work through the situation of Ukrainians vis-a-vis Russia couldn’t help but remind me of last year’s SEELANGS race debacle which actually stemmed from a conversation about Ukraine. I recall that it was set off when a lack of sufficient vocabulary to discuss Ukrainian self-determination and its subaltern identity led to an analogy about African-Americans. Thus Pussy Riot’s “I Can’t Breathe” video, which similarly borrows from contemporary racial discourse in America to work through the Ukrainian crisis, left me wondering if there was not a pattern here. Why do American race relations reappear over and over again in discussions of the minority experience in the former Soviet Union?

Just the other week, I spoke to a group of American college students about Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov and his new novel, The Underground (2014), which follows the story of 12 year-old Mbobo, a young boy living in Moscow who is the offspring of a Russian mother and an African athlete who participated in the 1980 Olympics. Though Ismailov has said in interviews that the character was inspired by Pushkin, he nonetheless uses Cold War language regarding “friendly [African] nations” to describe Mbobo’s father. I asked the students why they thought Ismailov chose to work through his own experiences as an ethnic minority in Russia through the language of black struggle. Puzzled, they asked, “yeah, why doesn’t he just talk about being Uzbek?” Indeed-- why not?

I mention this because when I decided to teach a class at RGGU (the Russian State University for the Humanities) on the Harlem Renaissance, I was assured I was teaching the students something entirely new to them, that it was the first course on African-American literature to be taught at RGGU. Before the first lecture, I was introduced by the program director with the following words: “Jennifer is here to teach us about black literature and culture, of which I think we would all agree we know very little.” However, the truth is that they and many Russians in fact know quite a lot about black culture. Not surprisingly, as inheritors of Soviet curricula, the students in my class had read Uncle Tom’s Cabin in school to learn about the evils of American racism. One of the students even knew the words to the popular Negro spiritual “Go Down Moses,” and started to sing it for the class. Indeed, I think we often forget that since the days of the Soviet Union, Russians have participated in a long and rich conversation about American race relations and the legacy of slavery, one of the few silver linings of the Cold War. As such, it should not come as a shock that Pussy Riot and Hamid Ismailov use language and imagery rooted in black American struggle to describe more local conflicts based on nationality and minority identity.

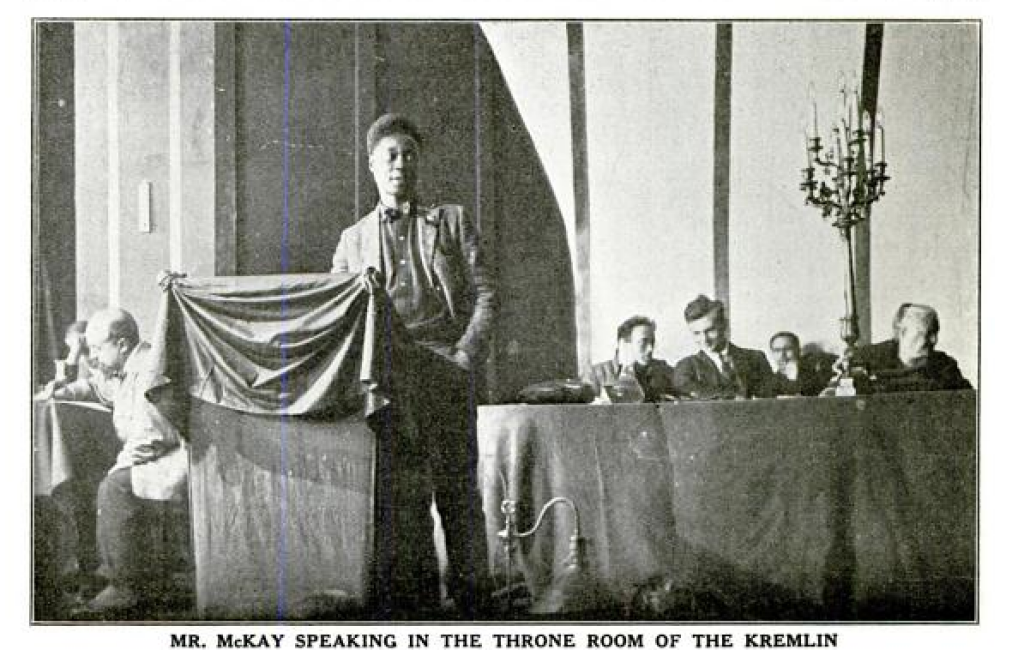

The course at RGGU, “The Harlem Renaissance: From New York to Tashkent” is an overview of the Harlem Renaissance that blends an understanding of “the New Negro Movement” as we usually think of it, based in north Manhattan, with a reflection on Harlem Renaissance writers and thinkers who wrote about and traveled to the Soviet Union. It was this aspect, the Russian side, that most surprised and captivated the students in the course who were surprised to see old photographs of Claude McKay and Langston Hughes in Moscow and Tashkent, respectively.

Our first meeting was a broad introduction to the visual art, music, and literature of the Harlem Renaissance. However, it was very important for me to explain to the students why this outpouring of black artistic expression occurred when it did and what exactly this “renaissance” was a “rebirth” from. This necessitated a long conversation about slavery in which I showed images of slaves who were brutally physically punished for learning to read and write. I talked about early efforts at black artistic expression, including Negro spirituals and work songs, as well as the African-American tradition of quilting. After showing images on this last point, one of the students expressed a desire to write her final research paper comparing Russian and African-American female quilting practices! As I was talking about the institution of slavery, its postbellum perpetuation through sharecropping, and Jim Crowe laws in the South, one thing startled me and left me a little off-kilter—no one looked uncomfortable.

It has been my experience that conversations about race make white Americans very nervous. Just this past week on Jeopardy, the contestants left the category of "African-American History" for last, opting to first answer questions about “Kiwi Fauna” before taking on the queasy subject of race. In the best cases, many white Americans are simply afraid of offending. Others, though, find discussions of slavery and Jim Crowe to be a personal indictment that makes them feel either guilty or angry that they should be made to feel guilty. There are others still who resent contemporary social policies that are based on the philosophy of reparations, and find in conversations about slavery and racism justification for what they see as “reverse discrimination.”

My Russian students, however, are free off any of that emotional and political baggage; it’s not their history. I confess, I was prepared to be in a defensive mode (as one often has to be), and yet what I found were people who did not question my authority or experience when it came to racism in America. Moreover they expressed outrage on my behalf. When I told them that the Emancipation Proclamation was printed on paper containing large amounts of cotton, one of the students interrupted me in horror—“it was printed on cotton picked by slaves?!” I was so moved by this expression of sincere sympathy, and at the same time sad that I rarely met with it at home. To find it here in Russia, in a country widely agreed to be emotionally and sometimes even physically unsafe for people of color, left me with the feeling that something in me was about to be transformed. I am not exactly sure what that is yet, but I know that I have never felt more at ease living in Russian than I have after teaching that first class.

Over the course of the semester, I will be blogging for All the Russias about my experience teaching this course. I will share some of the material that I am using for the seminar along with anecdotes from class. Of the latter, there is one story from the first seminar meeting that I absolutely must share. When I asked the students what they knew about Jim Crowe, one of them said she knew that public buses were segregated in the American South. Excited that she knew about this (and also because I was Rosa Parks in a school play in the 1st grade), I asked a follow-up question, “And does anyone recall the name of the black woman famous for refusing to give up her seat on the bus?” One student responded, “Yes of course. Condoleezza Rice.” Condi, it seems, has quite the legacy here…