When Ryan Fogle, Third Secretary at the American Embassy in Moscow, was arrested for attempting to recruit a Russian security-services officer, the world sat up and took notice. Then it snickered and sat down again.

Still, there's something mildly instructive in the latest speedbump on the road to good US/Russian relations. Of course, everyone knows that the Americans spy on Russia, and that the Russians spy on America, but each time, we are shocked—shocked!—at each other's bad behavior. This is particularly evident in the video in which an FSB officer stands next to Fogle and feebly manufactures a facsimile of outrage that the US is spying on Russia, even as the two countries are cooperating so well in the Boston bombing investigation. In reality, the actual bilateral cooperation lies in providing a spectacle of diplomacy shadowed by a pantomime of espionage, where the cloak and dagger have been borrowed from a community theater props department.

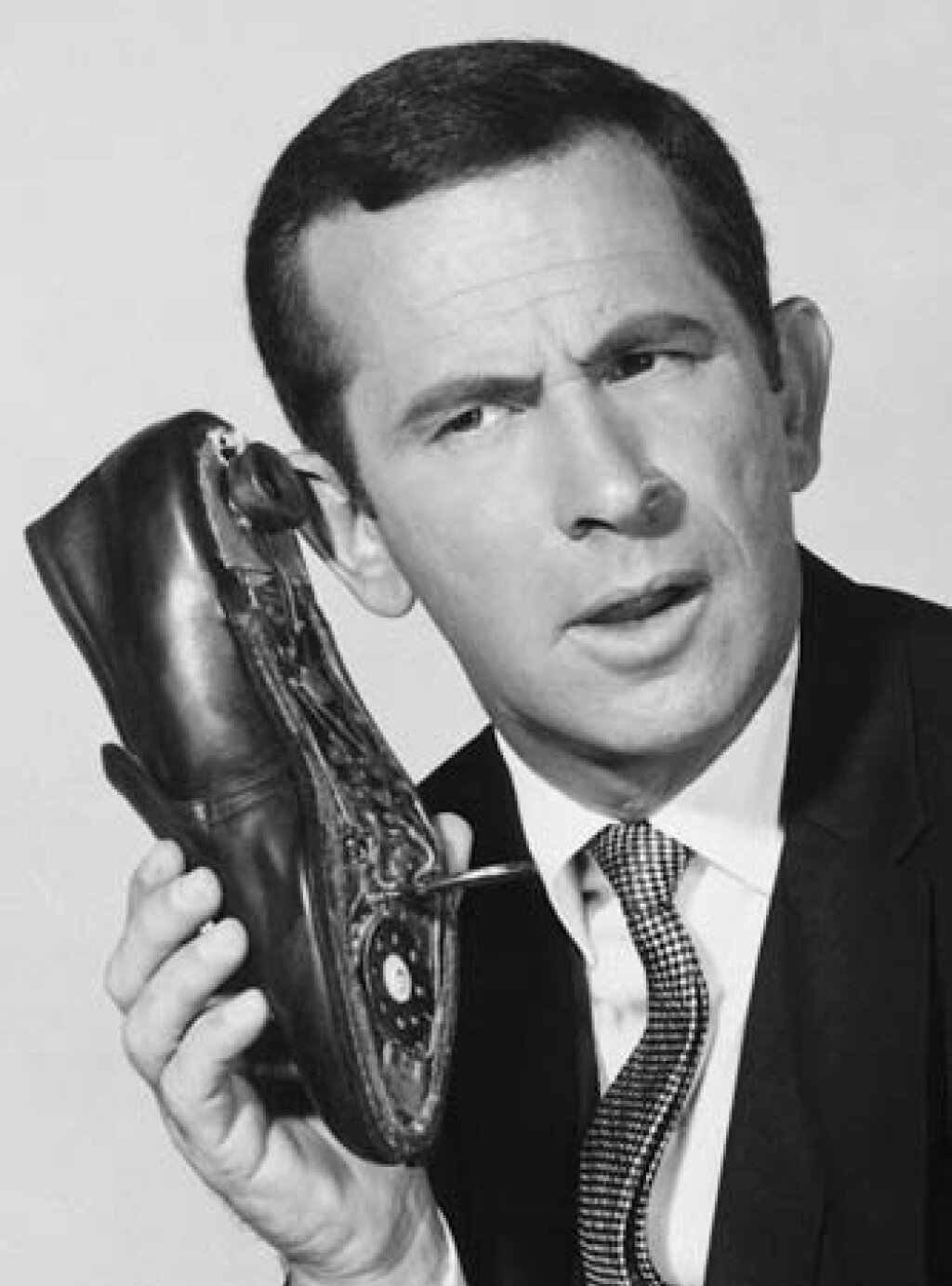

Fogle was caught with wigs, a Moscow guidebook, and a compass. The last item has been a particular source of amusement, since there's nothing suspicious about someone trying to navigate city streets by staring at a compass (presumably, he saved his sextant for night missions). Even more amusing to the Russian blogosphere is the letter he was carrying to hand to his Russian target. The letter was written in such convoluted, un-Russian Russian that one suspects an automated translating program was involved. Moreover, the form of address ("Dear friend") was presumably chosen for the sake of anonymity, but ends up reading like Nigerian spam. One wonders if Fogle's target first had to give his banking data and pay "a small fee" to facilitate the transaction. Will the next American spy nabbed by the FSB be peddling "natural male enhancement"?

Pundits have been comparing Fogle's arrest to the Anna Chapman scandal. Even those with short memories probably still recall the 2010 discovery of a Russian spy ring in Montclair, New Jersey, homeland of enlightened multiculturalism and skyrocketing real estate. In that case, ten foreign nationals were identify as "illegals," masquerading as suburbanites while gathering information that was freely available on Google. With a cover story only slightly more convincing than that of the Coneheads ("We are from Canada"), they registered as a cross between a spy scandal and a reality show. The general reaction in the States was amused nostalgia rather than outrage. It's as if the long-lost Pottsylvainain agents Boris and Natasha had stopped hunting for Rocky and Bullwinkle in the real world, and started to stalk them on Facebook ("Must friend moose and squirrel.")

Part of the amusement in all this is that the entertainment industries of both countries have spent decades creating the myth of the superspy. Shtirlitz always avoids capture while Jack Bauer never has trouble getting a cell phone signal. One of the few virtues of FX's The Americans (a show we've featured on this blog twice) is that its depiction of analog-era spying occasionally allows it to be messy; an episode in which the Russian illegals accidentally kill an FBI agent has real repercussions, but it's structurally a farce--dispensing with the dying agent Amador puts Keri Russell in the same position as Christian Slater in Very Bad Things. Indeed, the Fogle story looks like The Americans fan fiction (wigs always work for Matthew Rhys).

Film and television have set the bar for real spies awfully high, with the result that the actual spies who are caught end up looking like amateurs in a bad imitation of Ian Fleming. It's hard to imagine that the information gathered by either side would make a huge difference geopolitically. The insistence on continued espionage looks like an attempt by both sides to make a show of vigilance, and to remind their respective domestic audiences that post-Cold War US/Russian relations are still serious business.

But they're no longer the best show around.