Oksana Rosenblum is an art historian and translator residing in NYC. Her projects include visual research for museums of Jewish History in Warsaw and Moscow.

Yevgeniy Fiks’ solo exhibition “Himl un erd: Yiddish Cosmos” at Stanton Street Shul in New York (on view Sundays from 1–6pm, Mondays & Wednesdays from 4–7 pm, November 18–December 16) explores the connections between the twentieth-century experience of Eastern European Jews and the Soviet space program. What unites these two seemingly unrelated stories?

To understand the connection, we must turn to the origins of the Soviet state. Political utopianism brings with it art, literature, and culture that flourish in periods of social change and upheaval like the one immediately following the 1917 Russian revolutions. At that time, a conglomeration of various art movements, loosely united under the name of the Russian avant-garde, swept the capital cities of the former Russian Empire.

Jewish artists, who had for many decades been confined within the Pale of Settlement, were no longer geographically limited. Their imagination, too, knew no limitations. They drew inspiration from impressionism, cubism, and the recently invented Suprematism; from traditional ritual art and romanticizations of life in the shtetl; and sometimes arrived at the negation of figuration or religious experience, moving beyond conventions of form and content.

They felt that their geometric, analytical forms connected directly to the world of technological efficiency that they identified with the immediate future. Accordingly, El Lissitsky conceived his humanoid New Man as living in a world of industrial design, collapsible furniture, moving sidewalks, revolving doors, and clothes with detachable parts.

Anarchism may not come immediately to mind in a discussion of the avant-garde; yet on a conceptual level, it played an important role in the development of avant-garde art. As Constructivist artist Varvara Stepanova explained in a diary entry from 1919, “Russian art is anarchistic in its principle as Russia is in its spiritual path. We have no schools, and each artist is a creator, each is original and drastically individual.”

At the turn of the century, various anarchistic philosophies spread throughout the Russian intelligentsia, seeking to liberate the individual from the norms and dogmas of social hierarchies and provide a favorable climate for spontaneous creativity. Anarchism shifted the focus of the creative process toward the fresh and unexpected (children’s art, spiritual and esoteric art, art of the non-western societies). It was animated by the belief that various human ideals could co-exist, that life could be lived close to nature, and that even death could be negated. According to Leonid Heller, anarchism presented one way of serving the Revolution. It is no wonder, then, that important avant-garde artists like Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexandr Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and Aleksei Gan held anarchistic-adjacent ideas and even published in anarchistic periodicals.

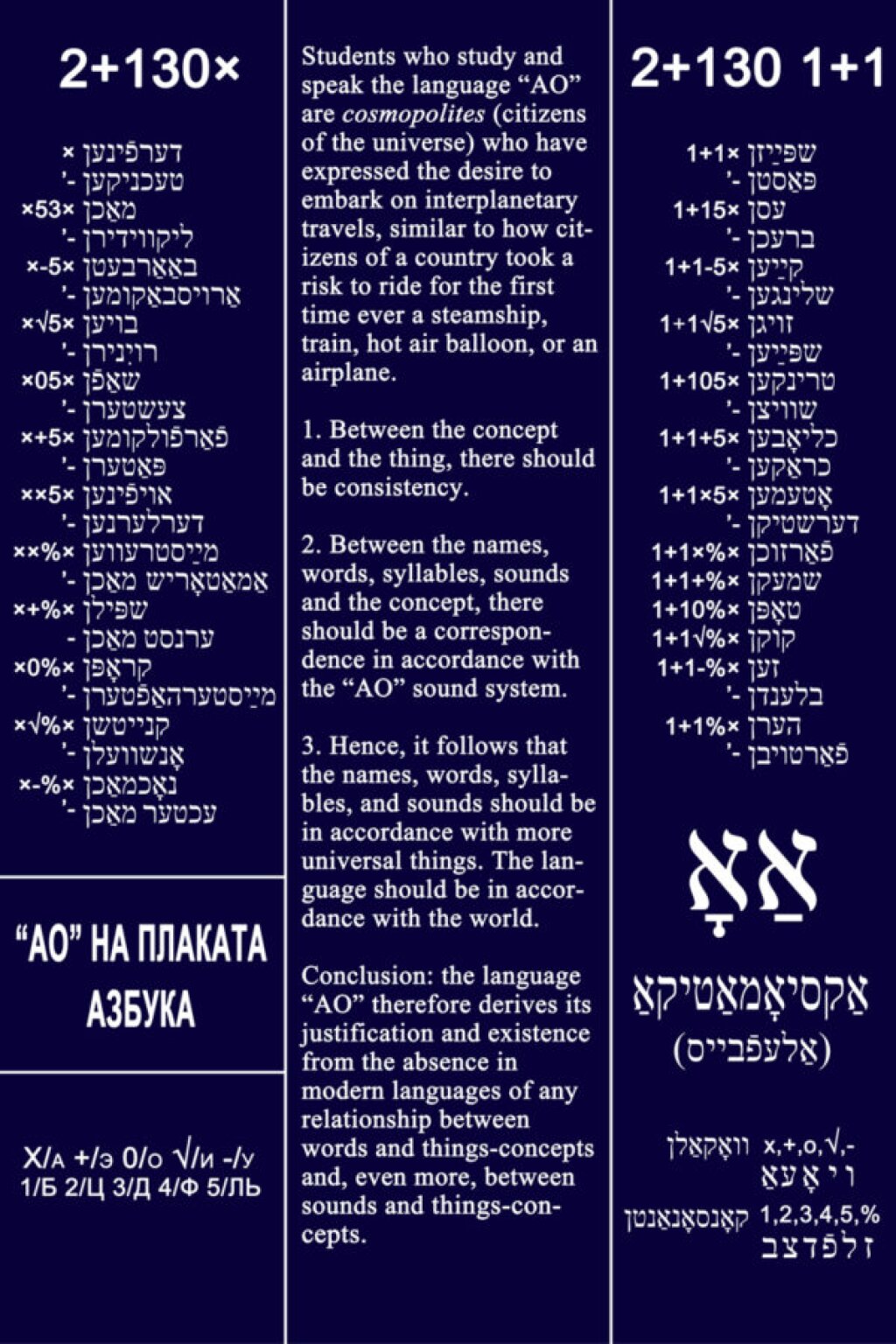

The revolutionary spirit dictated that the construction of a new society required the creation of a new language, so that inhabitants of all worlds, everywhere, could communicate. Volf Gordin, a prominent anarchist theoretician, accordingly proposed the idea of a universal language, which he called "AO," in 1920.

It is worth taking a step back to discuss the Gordin brothers, Abba and Volf. Born into the family of a Lithuanian rabbi, they were fluent in both Hebrew and Yiddish. They spent their seemingly boundless energy on organizing the pan-anarchist movement, but their approaches differed. Abba at first attempted to work together with newly inaugurated Soviet power, but, having failed at that, found himself in exile and later escaped to the USA. Volf, on the other hand, remained in the Soviet Union and invented the "AO" language in 1920. The purpose of AO, like the earlier Esperanto, would be to unite the various inhabitants of the Universe, or cosmopolites, under a single linguistic umbrella. A circle of so-called inventists formed around Volf, who later turned to Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, an early Soviet rocket scientist, to ask for his support in spreading the word about AO.

In April 1927, the First World Exhibit of Models of Interplanetary Mechanisms and Devices took place at the Association of Inventists in Moscow. The largest display at the Exhibit was dedicated to AO and explained how the language worked; it also contained grammar books and numerous related newspaper articles.

“Those who study and speak AO, are cosmopolites — citizens of the Universe”, read caption to one display.

Yevgeniy Fiks' Stanton Street Shul exhibit draws deeply on this utopian history. His AO prints are visually bold and conceptually complex, unearthing and bringing to life an all-but-forgotten, substantively failed, yet beautiful attempt to create a universal language capable of overcoming national and state boundaries. AO was meant to be simultaneously as precise as a mathematical formula but inspirational enough to motivate its bearers, the cosmopolites, “to set off on an interplanetary voyage,” as one of the prints poetically states.

Between the New Human Being, a new language, and aspirations for a new world order, a sense of utopia is born. It starts as an energetic welcoming of the future; however, it inevitably ends with a future that fails to deliver on utopian promises.

The pre-Second World War life of Soviet Jewry was full of promise. Initially accepted as equal members of society, having in many ways forgotten their shtetl roots and abandoned Judaism (not necessarily by choice but as a result of a massive anti-religious campaign), they felt needed and were passionately involved in the creative process of birthing a new society. This brief period of relative optimism was not to last, however. Soviet victory in the Second World War demanded a uniform narrative incapable of accommodating either the tragedy of the Holocaust or Soviet Jewish heroism on the frontlines.

Ironically (or perhaps not!), the notion of a “cosmopolite” took on a different, sinister connotation during Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign in 1948-1953, when the brightest representatives of the Jewish intelligentsia were accused of anti-patriotism and pro-Western attitudes. The campaign reached its culmination during the Night of the Murdered Poets on August 12, 1952, when thirteen Soviet Jews were executed, including a constellation of Yiddish poets, writers, and actors that included Peretz Markish, Dovid Hofeshteyn, Itzik Feffer, Leib Kvitko, David Bergelson, and Benjamin Zuskin.

Even after Stalin's death, Soviet anti-Semitism did not subside, instead continuing to target the country’s most "cosmopolitan" citizens. Jews were expelled from scientific and cultural institutions, editorial boards, and governmental and managerial positions. An anti-religious campaign in the late 1950s and early 1960s saw the closing or burning of synagogues and the desecration of cemeteries. As of the late 1960s, the “Let My People Go” movement made emigration for some Soviet Jews possible, even as many were not allowed to leave and became so-called "refuseniks." In the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, did the Jewish emigration to Israel, Germany, and the United States achieve gigantic proportions.

Yevgeniy Fiks’ concept for the exhibition on Yiddish Cosmos draws on all these important artistic, philosophical, and cultural traditions: from pananarchism to cosmism to the Russian-Jewish avant-garde.

The idea of developing a new body fit for the New Man, first articulated by artists like El Lissitsky, did not disappear during the demise of the avant-garde in the late 1920s. Indeed, the notion of a socialist superman persisted and even thrived during the Stalin era. Socialist Realism, advanced in the early 1930s, nurtured the image of a healthy, youthful, and radiant hero, paradoxically dovetailing with the traditions of the avant-garde.

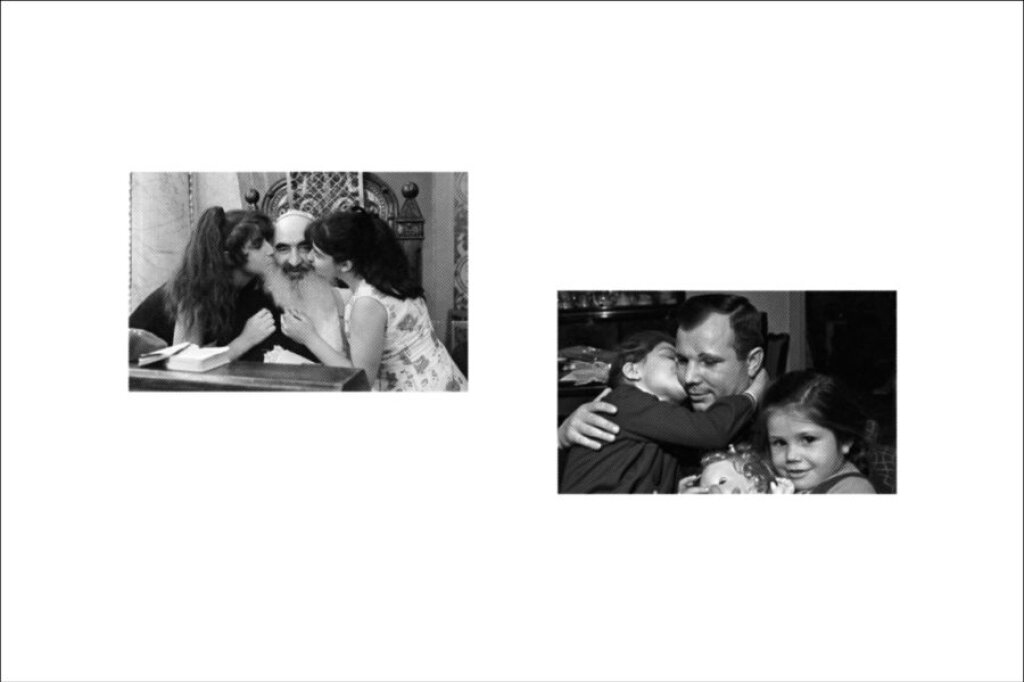

Perhaps no one else symbolized the concept of the Soviet hero as effectively as cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin (1934-1968), the first man to successfully journey to space. In Fiks’ prints, this Soviet superman appears in deceptively human light: here he is, stroking a cheek of an unknown boy or hugging his own daughters. Fiks highlights the contrast between the space-suited superman ensconced in complicated machinery with the ordinary man surrounded by his family.

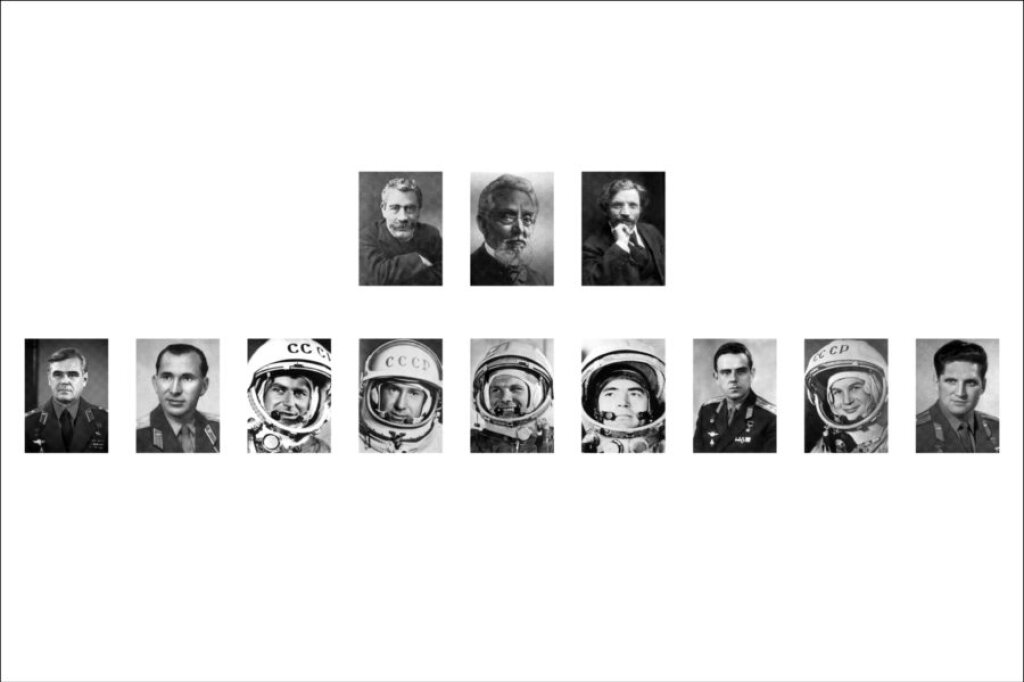

Yevgeniy Fiks’ works show how the traditional “superheroes” of Jewish culture – rabbis – were substituted with the cosmonauts, how the pathos of studying Torah gave way to the pathos of new discoveries and open frontiers. The assimilated Soviet Jews of the 1960s, 70s, and late 1980s, would likely regard the Torah scroll as an object no less foreign and unknown than a spacecraft. Indeed, there would scarcely be any place they could encounter religious paraphernalia; religious fervor would be sublimated into a passion for scientific progress and inter-planetary communication — a cosmic cosmopolitanism.

Fiks' exhibition opens a new pathway for its viewers, allowing us to witness the creation of a new canon in which Sholem Aleichem’s face merges with Gagarin's. The works at Stanton Shul create a playful and a somewhat surreal effect by imagining a reality in which the unlikely juxtaposition of these two figures does not produce cognitive dissonance. For instance, a print depicting three Yiddish writers and nine Soviet cosmonauts confronts the viewer with the all-too-familiar Soviet institutional practice of displaying photographs on the doska pochyota [honor board], a special place dedicated to rehearsing the pantheon of officially "famous" personalities — politicians, scientists, local shock-workers, and so on. The top row of Fiks' print, however, features portraits of “cult” Yiddish writers. Y. L. Peretz, Mendele Moykher-Sforim, and Sholem Aleichem gaze at the viewer with an intellectual intensity at odds both with the forced solemnity of the officially clad astronauts in their medal-covered suits and the playfulness of their spacesuit-wearing colleagues in the bottom row. The viewer’s gaze rests on the consummately human expressions of the top figures, which contrast sharply with the bottom row's suggestion that "clothes make the man," be they of cloth or space-age synthetics.

Stanton Street Synagogue provides Fiks' exhibit with an intriguing setting. On the ground floor, beautiful paintings of mazalot (Jewish astrological signs) adorn the walls. Fiks' works reside in the sizable upper gallery with two sides. I walked to the end of one gallery wall, almost certain it connected to the other side, only to discover that it was a trompe l’oeil. Perhaps the space itself is a subtle reminder of the paradoxes of Jewish life in the Soviet Union. How difficult it was to be both Jewish and Soviet at once — to desire to transcend the boundaries of one’s nationality and culture and yet, to be painfully reminded by the surrounding environment of the impossibility of that effort. No wonder the space program offered an escape, however imaginary.