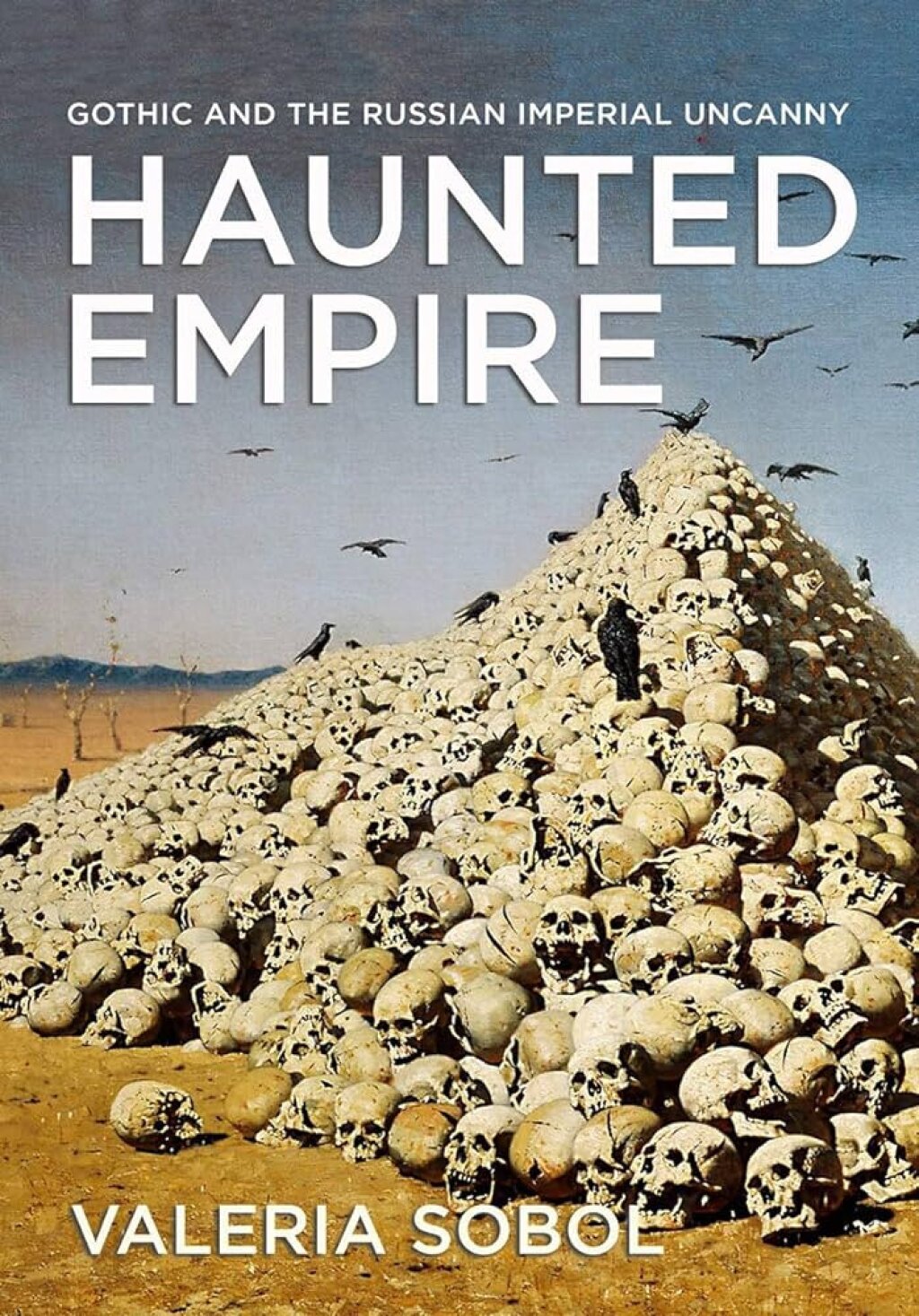

Valeria Sobol is Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. This post is an excerpt from her Haunted Empire: Gothic and the Russian Imperial Uncanny, a Northern Illinois University Press book published by Cornell University Press. Copyright (c) 2020 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher

In 1836, Petr Chaadaev published his famous first “Philosophical Letter” (written circa 1828-29), where he defines Russia in almost exclusively negative terms as lacking identity, history, any contribution to civilization, and even a definite facial expression:

I find that even in our gaze there is something strangely vague, cold, uncertain, which resembles somewhat the facial appearance [physionomie] of the peoples who are placed at the very bottom of the social ladder. In foreign countries, especially in the South, where the features [physionomies] are so animated and expressive, so many times, when I compared the faces of my compatriots with those of the locals, I was struck by the muteness of our faces.

This lack of a clearly defined expression in the Russian people’s faces is a literal counterpart to Russia’s absence of a national “physiognomy”—a concern that pervaded Russian literary criticism of the time and found its manifestation in such uncanny fictional characters as Klim Diundik in Pogorel’sky’s The Convent Graduate, with his markedly indistinct appearance, which I discuss in Chapter 5 of my book. Significantly, Chaadaev associates the coldness of expression and the lack of animation in the Russians’ faces specifically with Russia’s Northern identity. Moreover, just as he was struck by the facial “muteness” (l’air muet) of his compatriots, he is amazed by the void of Russia’s “social existence.”

Characteristically, Chaadaev interprets Russia’s imperial expansion (this time along the East/West axis) as a compensation, or even a “cover-up,” for this void, for the lack of identity and historical significance: “In order to make ourselves noticeable,” he states somewhat sarcastically, “we had to stretch ourselves from the Bering Strait to the Oder.”

Russia’s early history fares no better, described in quasi-Gothic terms as the era of “brutal barbarism, crude superstition,” and cruel foreign rule. The “sad story of our youth,” for Chaadaev, is a story of a “dull and gloomy (sombre) existence, animated only by heinous crime and softened only by servitude.” With its history of darkness, violence, and isolation, Russia itself becomes a Gothic trope, a “maiden in a dungeon,” as well as an uncanny space of emptiness.

While Chaadaev was rather unique for the shocking directness with which he expressed his verdict, his concerns about Russia’s historical development, the originality and authenticity of Russian culture, the implications of its geographical location, and, importantly, the relation of its imperial expansion to national identity were clearly shared by his contemporaries. This book has argued that these anxieties underlay a number of literary works of the time that deployed, seriously or subversively (and often both), popular Gothic tropes. The Gothic conventions, I have maintained, served not only as purely literary techniques intended to create a mysterious and suspenseful atmosphere in the work, to provoke certain emotions in the reader, or, in some cases, to mock a fashionable literary form. Domesticated in the Russian imperial context, these Western literary conventions found themselves in a different dom (home)—in a vast amorphous empire, whose problematic history, geography, and identity they unexpectedly and uncannily bespoke.

The tradition of the Russian imperial uncanny that I trace in this study begins in the North, with Karamzin’s interrogation of Russia’s alternative past in the Gothic mode in his “The Island of Bornholm” and with the Decembrist writers’ obsessive Gothicizing of medieval Livonia—a region both accessible and irrevocably distant, Russian and not, in their own time; a repository of the heroic and Romantic Middle Ages but also of bloodthirsty feudal cruelty. But in its most spectacular form in Russia’s “Northern” Gothic, the imperial uncanny unfolds in literary and ethnographic works dedicated to Finland, the land of wizards and gloomy desolate cliffs. An old neighbor/relative and a recent exotic colony, the docile imperial subject and a dangerous and destructive irrational force, uncanny Finland is most vividly represented by Odoevsky in his novella The Salamander.

In the meantime, in the imperial “South,” Gogol and Pogorel’sky almost simultaneously create uncanny representations of Ukraine as both a threatening alternative to Russian imperial identity and an idealized double of Russia’s lost authentic self. Both writers deploy Gothic tropes to question Russia’s imperial dominance over Ukraine, which Pogorel’sky exposes particularly powerfully through his portrayal of a complex play of colonial mimicry. The imperial uncanny of the Russian Southern borderlands culminates in the liminal space of Lermontov’s “Taman’,” discussed in the introduction, with its disorienting anthropology and geography. Finally, Kulish’s Walter-Scottian novel offers a deeply ambivalent and nostalgic Gothic vision of the heroic Ukraine of the past, which pays a heavy price for its inclusion into the Russian imperial order.

As I was working on this project, something truly uncanny happened: first, Russia annexed Crimea in the aftermath of the Ukrainian Maidan Revolution, then started a hybrid war in Eastern Ukraine. In February 2022, about a year and a half after the book first appeared, Russia began a full-scale war against Ukraine. How contemporary Russian and Ukrainian cultures are processing this historical experience, also traumatic in its own way, is a subject for a different project. Mine started as an exploration of the past, which, unfortunately—and in a truly Gothic manner—has made its way into the present.