Watch the video of the event here

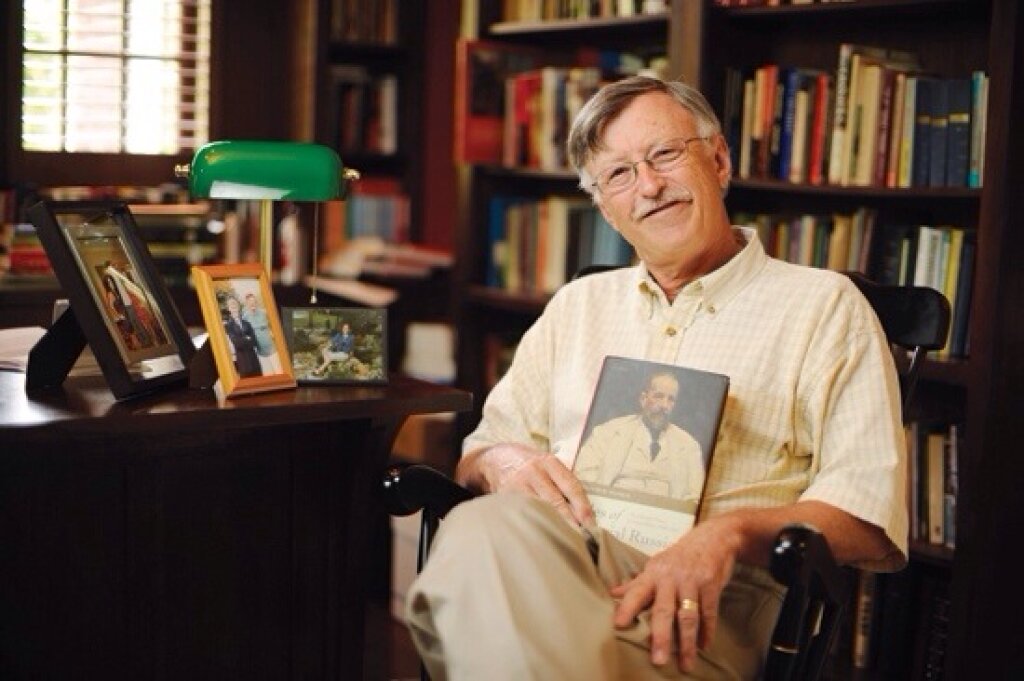

Thursday morning March 6th the Jordan Center welcomed Frank Wcislo, Professor of History and Dean of the Ingram Commons at Vanderbilt University. Director Yanni Kotsonis introduced Wcislo’s work in as an historian of late Imperial Russia. Wcislo is the author of several books including the very well reviewed work, Tales of Imperial Russia: the life and times of Sergei Witte, and his most recent work looks closely at the years 1914 to 1918, what Wcislo dubs “the last years of autocracy.”

Wcislo introduced this latest book project, one he’s been at work on for the past two years, as stemming from Witte’s fascination with power, and more specifically the royal couple-- Tsar Nikolas II and Alexandra. “He found [Alexandra] to be a fascinating and an, ultimately, unfathomable character,” Wcislo said. This view is very much in stark contrast to the widely held perception that the pair were less than intelligent and even less interesting, Alexandra in particular.

However, Wcislo said, the correspondence between the couple, which dates back to their courtship and consists of immense collection of letters, photographs, and other keepsakes, offers a plethora of revealing insights into imperial culture. These archives allow the Tsar and Tsarina to be analyzed within the context of the court. “I found myself thinking more broadly about this world that had disappeared and collapsed,” Wcislo said.

He explained that as the author of what he hopes to be an historical novel, he will offer a cultural history of this particular group in late Imperial Russia. Wcislo and just a few of his colleagues in grad school started out with an interest in the bureaucracy. “This really made us odd balls during that time of a particular generation’s obsession with revolution from below,” he explained.

But why this book, and why now? Wcislo said that he was inspired by the various experiences of revolution and regime change all over the world in the past several years. The Arab Spring in particular was fascinating to Wcislo, who said that as a result of these events he “got to thinking more carefully about collapse and disintegration.”

Specifically Wcislo is curious about the ways in which governments, regimes, and dictators with a seemingly tight grip on power, suddenly collapse. “How is it that, well, not so much that they are overthrown -- there are whole libraries for that -- but rather, how do they allow power to slip through their fingers?”

Wcislo said that in his role as Dean of the Ingram Commons at Vanderbilt, he’s constantly dealing with the question of organizational success and failure. The ways in which individuals function within organizations is something that is universally fascinating, he argued. “There’s nothing more fundamental to our human experience than the relationships between people in organizations,” he said.

Yanni Kotsonis commented that Wcislo’s project was very much in order, given the lack of an informative history of Nikolas II. But Kotsonis wondered what Wcislo means by Imperial Culture.

Wcislo responded that when he uses this term, he’s talking about the Imperial court, military officers, party leaders, and “possibly the Church.” But he said what’s important here is that, “the autocrat is the centerpiece of this system and the glue that holds it together...the key moment in the Revolution of 1917 is the abdication.” Wcislo said that members of the Imperial Culture were “stunned,” by Nikolas’ decision.

Wcislo also outlined what he means by “the autocracy”-- “it’s a system of affinity groups and cultures that are plugged into the autocratic system.” He explained that looking at Imperial Culture this way was important because of the inappropriateness of the descriptor “elite,” which does not wholly capture this group for several reasons, one being that the term simply wasn’t in use at the time.

“So how do you get at an understanding of this?” Wcislo said. Picking apart the ways in which groups within the Imperial Culture interacted is essential to understanding what role they played in systemic collapse. He pointed to Vitte’s belief that “ultimately Russia wasn’t a civil society, it was a military state.” Wcislo highlighted the fact that Alexander was always decked out in military garb, which indicated, “the power of the state ultimately rested in military power.”

Through his research thus far, Wcislo discovered several apparent similarities between these groups which led to organizational failure, and may have contributed to collapse. Firstly, military culture was characterized by the “caste-like isolation of the officer corps,” which rectified and maintained “idealized cliches” about the soldier’s duty to his country. Wcislo described this as a strict emphasis on hierarchy and subservience which was “assumed at a basic, cultural, genetic, and DNA level.”

Even in the face of the unspeakable atrocities of World War I, and what Wcislo called the “meat grinder effect,” soldiers were remarkably obedient to the Tsar. “Ironically [the caste identity] was solidified further with all the casualties of war.” The system became even more militarized in the years leading up the 1917, and as a result Nikolas was pulled further into the military, and consequently became increasingly out of touch with the civilian bureaucracy, what Anne Lounsbery pointed out was closer to “real life.”

Secondly, the military, bureaucracy, and the court maintained their attractiveness because of the perceived end game, which offered guaranteed status, power, and influence.

Thirdly, Wcislo says there was distinctly weak leadership in that those at the helm, “really had a lack of comprehension about the people they rule or manage.”

This symptom was also evident in looking at the groups as a whole. A fourth characteristic, Wcislo explained, was in how these groups suffered from silo syndrome-- when institutions or groups feel that they exist basically in a vacuum, and whatever lies outside that vacuum is an immutable other with static paradigms. Thus effective communication across these groups was also stunted given the widespread basic misunderstanding regarding those outside one’s own group. “Silos kill this regime,” Wcislo argued.

All of this was grounded in a fifth characteristic -- an emphasis on routine and tradition which offered a predictable outcome. Wcislo explained that it was widely believed that instances of “past greatness are predictors of future success.” He argued that “clinging to this is deadly,” in a rapidly changing and increasingly innovative world.

Finally, Wcislo pointed out that he had uncovered a widespread “disconnect between vision and reality.” For example there were a great deal of massive projects planned in hopes of reforming the system, yet an obvious lack of resources to fund them.

Anne Lounsbery pressed Wcislo to explain how the central elites could hold onto faith in the inevitability of a positive outcome for the regime for so long. “What sustains their illusions? What was it so impossible for them to look outside?” Lounsbery asked.

Wcislo explained that physical segregation had a lot to do with this, in that the stories circulated within these groups was a method of legitimizing the separateness.

Stay tuned for Wcislo’s forthcoming book.