This is the first installment of the Pelagia and the White Bulldog portion of “Rereading Akunin .' For the introduction to the series, and subsequent installments, go here.

If The Sound of Music had a threesome with Murder, She Wrote and The Brothers Karamazov, the love child abandoned on the church doorstep nine months later would be Boris Akunin’s Pelagia novels. A blood test would quickly rule out a Dostoevskian paternity, but nurture must not be automatically discounted in favor of nature.

I realize how facetious this statement sounds, but I stand by it. Here is how we are introduced to Pelagia in the first novel, Pelagia and the White Bulldog (2000), through the eyes of Bishop Mitrofanii:

“Even if one wished, it would be impossible to confuse her with anyone else: Her wimple had slipped over to one side, and protruding from under its edge in a manner quite shameful and impermissible for a nun was a lock of ginger hair, shimmering with a bronze sheen in a ray of sunlight.

Mitrofanii sighed, wondering yet again whether he had not committed an error when he gave his blessing to Pelagia’s taking the veil. It had been impossible not to give it— the girl had been through such great grief and terrible suffering that not every soul would have withstood it, but she was really not cut out to be a nun: She was far too lively, fidgety, curious, and undignified in her movements. But you are just the same yourself, you old fool, the reverend bishop rebuked himself, and he sighed again even more ruefully.”

Yes, who is Pelagia, really? A flibbertijibbet? A will o’the wisp? A clown? No, she’s just a red-headed nun who is far too spirited for her surroundings. If I were Mitrofanii, I’d hide the curtains, or else half the town will be dressed in them, belting out tunes so perky that the other half might welcome an Anschluss just to shut them up.

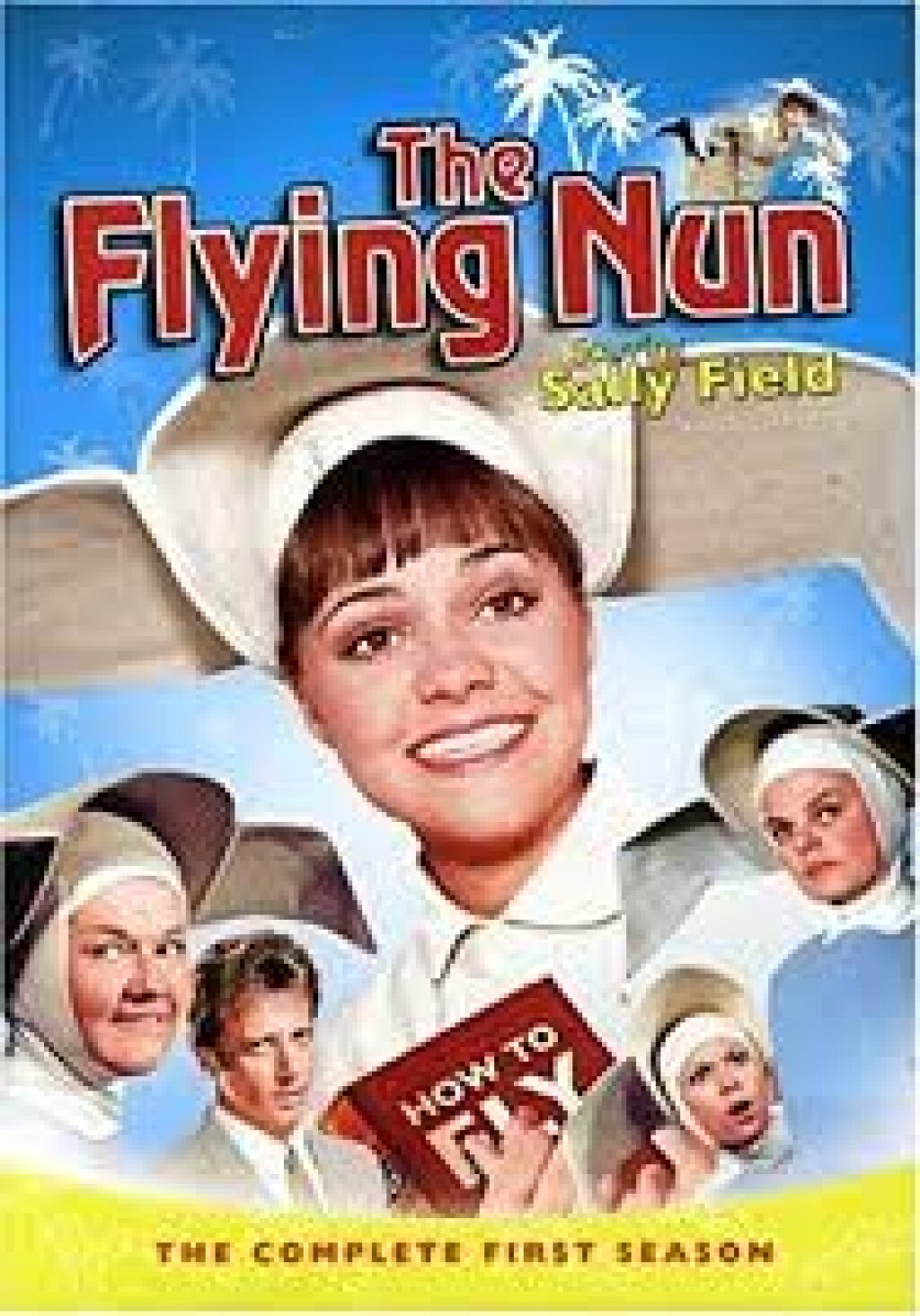

So Pelagia joins a long line of heroic, high-concept nuns. Chances are good that Akunin is familiar with a number of the classics. He must have seen The Sound of Music, may have watched Sister Act (but not Sister Act 2, surely), doubtless knows Chaucer’s anti-semitic Prioress as well as Agnes of God, and, as a former editor of Foreign Literature, maybe even Muriel Spark’s hysterically funny Watergate parody The Abbess of Crewe. He probably also knows about the dearly departed art critic Sister Wendy, but he cannot be blamed if he is unfamiliar with Sally Field’s early work as The Flying Nun (which was basically Dumbo in a wimple).

“High concept” is not a bad thing. In fact, it’s almost essential in a field as crowded as Russia's mystery genre, especially since much of the crowding is done by Akunin himself, who began his domination of the best-seller list around the time he produced his first Pelagia novel. And Pelagia stands out not just for her cloistered life; she is Akunin’s first female protagonist.

Let me state the obvious about the virtues of a female hero in a male-dominated genre. A good hero has to be both a type and a deviation from type; the hero has to have things that set them apart, usually a backstory. In a genre that is built around men, having a female hero in a story that is not set in postwar America or Europe means that there will simply have to be more backstory, more thought, put into how the heroine ends up in the situations in which she does. Even if you’re not a feminist, this is already more interesting than “I’m a detective. I'm a guy who got a license, and now I’m a detective.”

And it’s not necessarily all that feminist. The irony of creating space for a female hero in a pre-20th century setting is how literally patriarchal the backstories almost have to be: how many times is the woman spunky and educated because of Daddy? In Pelagia’s case, Daddy is not the responsible party, as far as I can tell. But she would never even have her amateur career if it weren’t for the generally liberal views of her bishop. Indeed, the entire novel revolves around the bishop: the problem with which he tasks Pelagia is basically his problem (or at least his family’s), and it is Bishop Mitrofanii who is the initial viewpoint character when we meet our heroine. Thus, for all her oddities, she comes to us pre-approved by a (literal) patriarchal figure.

Which is all fine. There is something jarring about recent American period films that insist on pretending that women could be just as assertive and independent hundreds of years ago as they are today. Akunin doesn’t do that. What he does, instead, is show that Mitorfanii has faith in Pelagia.

As for me, I don’t remember much about this book from nearly 20 years ago. But, like Mitrofanii, I have confidence in our heroine. Climb every mountain, Pelagia. You got this.

About the Plot

Bishop Mitrofanii’s great aunt, Marya Afanasievna Tatishcheva, is a rich old general’s widow who carries on her late husband’s passion project: bringing forth a new breed of canine, the White Russian bulldog. She has three generations of progenitors around her: Zagulyai, Zakusai and Zakidai. Zagulyai has just died, and she is convinced that someone poisoned him. She asks her nephew to come sort things out, but Mitrofanii sends Pelagiia, who has some unspecified experience in solving mysteries.

Pelagia sets out on foot, and soon a passing peasant gives her a ride in a cart. Together they stop at what turns out to be a crime scene: two headless male corpses have been discovered in the river. After she leaves, Pelagia is mortified to realize she is jealous of the police officer who has the chance to investigate an actual, serious crime.