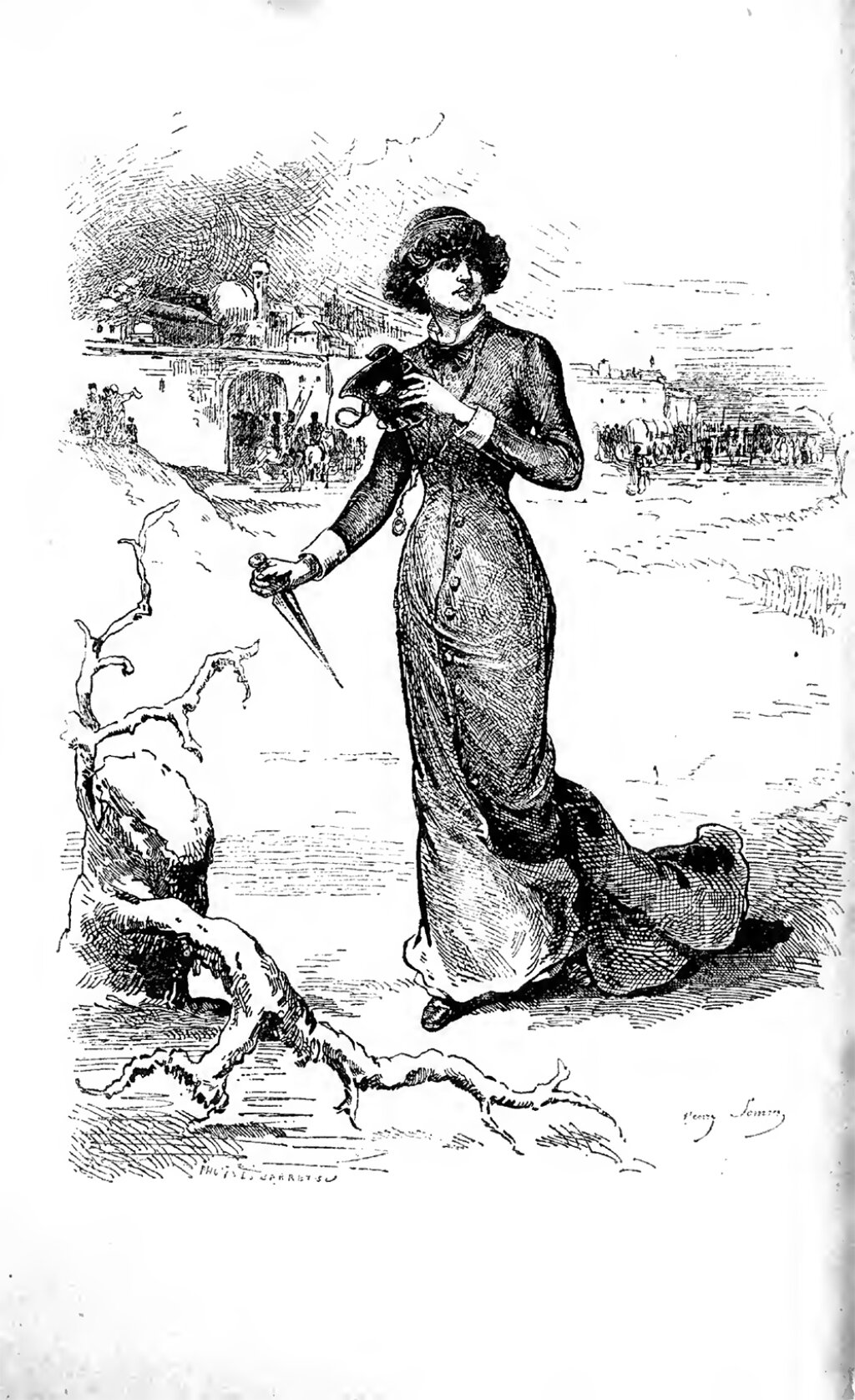

Above: The “portrait of the author” from the French epistolary novel Lettres d’une nihiliste par Alexandra, avec le portrait de l’auteur, 1880. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Abby Holekamp is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Chicago.

A sensational story about a Russian nihilist bomb plot gripped the imagination of the French reading public for a week in the autumn of 1906. The biggest mass-circulation newspapers published story after story about the search for the identity of “la jeune nihiliste russe”—“the young female Russian nihilist”—who had been apprehended in the southern city of Toulouse on suspicion of possessing a bomb meant for a Russian official traveling in the area. When she was arrested, she at first refused to tell police her name. Then, according to stories in the press as well as contemporary police records, she began to spin an increasingly elaborate but plausible life story that took her from a childhood in Odessa to schooling in St. Petersburg, higher education and radicalization in Lausanne, and from there to Paris and Toulouse with her fellow nihilists.

However, her story fell apart almost as quickly as she could tell it. Newspapers soon reported that, actually, the woman was not a Russian nihilist at all. Police never found a bomb, and the “pseudo-nihilist,” as she was now dubbed by the press, eventually admitted that she was lying about all of it. Her name was Jeanne Tilly, and she had been born in Brest, France, in 1887. Once it became clear she was not a Russian nihilist, the press lost interest in her case, and while we know she was subsequently acquitted on charges of vagrancy at the end of 1906, her later fate remains obscure.

We cannot definitively answer the question of why a provincial French teenager—the daughter of a baker and a vegetable-seller, with an average amount of formal education—undertook to create a character whose life story accurately mimicked that of actual Russian women who ran in revolutionary circles in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, we can explain how she was able to invent what one lawyer later called her “imaginary crime,” given the evidence that female Russian nihilists were well-known figures in fin-de-siècle France and Western Europe.

Though Tilly was not the only “pseudo-nihilist” living in France during this period, her case seemed to fascinate the press far more than the handful of others my research has uncovered. It is true that, in the press and in police reports from the 1880s onward, the terms “nihilist” and “anarchist” (in addition to “terrorist,” “revolutionary,” “radical,” and “extremist”) were sometimes used interchangeably, and frequently inconsistently. This confused terminology aside, the fact that journalists and commentators presented Tilly as a nihiliste — a specifically female nihilist — reveals the gendered nature of the fear and fascination this group of radicals garnered.

In addition to showing up in the press, so-called nihilists also appeared throughout the popular media. For example, five years before Tilly was born, a new wax museum, the Musée Grévin, opened in central Paris. The scale and intricacy of its exhibits was unprecedented; more than a collection of individual wax figures, it displayed full-scale dioramas inspired by history, literature, and current events. One such diorama depicted an imagined scene of nihilists being violently arrested by Russian police in an apartment full of real items imported from Russia, such as a samovar. This exhibit epitomizes how a combined desire for sensationalism and verisimilitude drove popular portrayals of nihilists. A few years later, the museum would outdo even this level of realism by spending thousands of francs to acquire the actual bathtub in which Jean-Paul Marat had been stabbed in 1793 for its new diorama depicting his murder by Charlotte Corday.

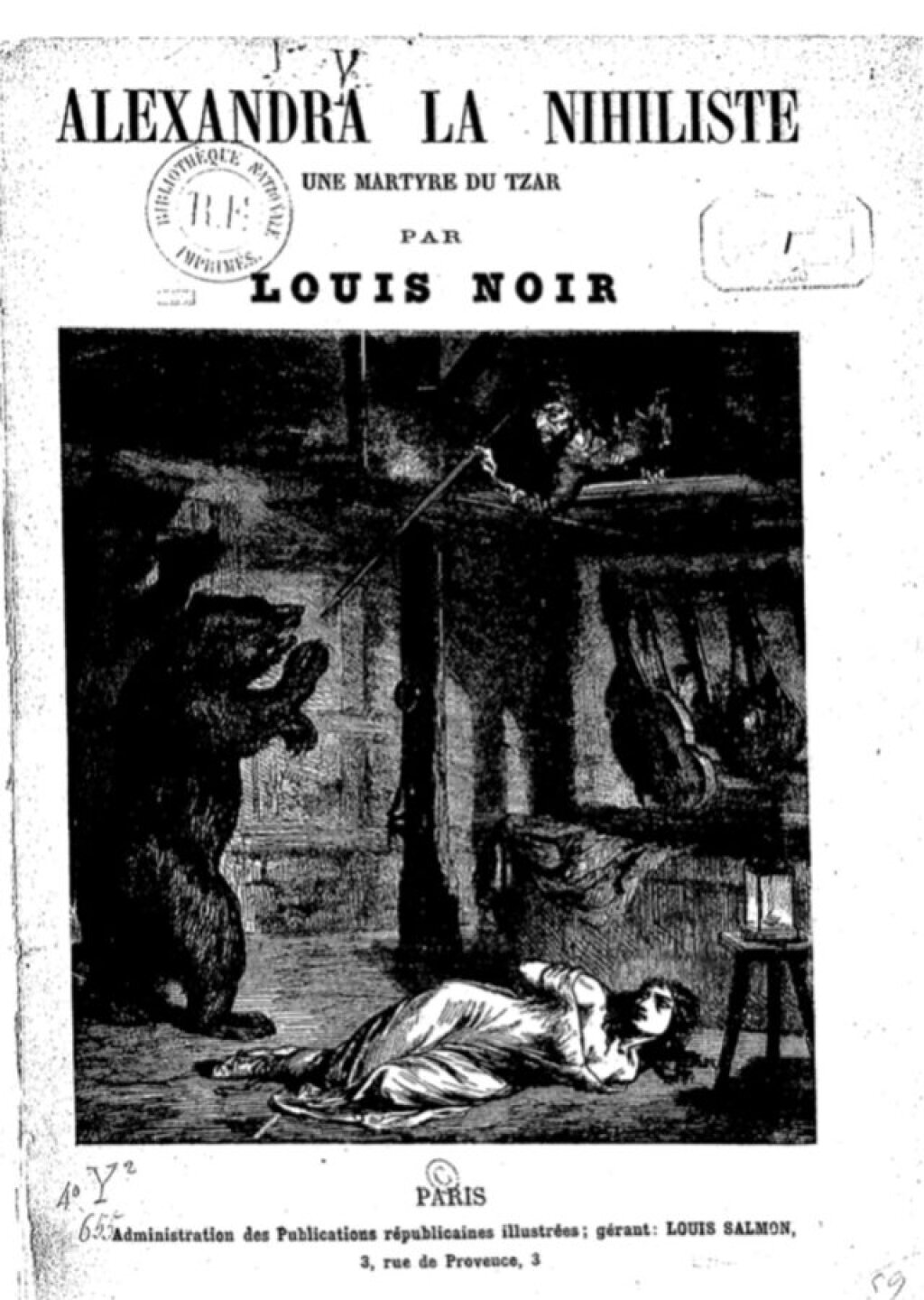

Compare that material scene to the press treatment of the burgeoning corpus of popular novels about nihilists. An 1880 review of the English translation of Ernest Lavigne’s French novel Le Roman d’une Nihiliste (1879) noted that, ‘‘to ordinary English readers, the incidents of this novel will certainly seem highly improbable,’’ but to those who know anything about ‘‘the internal condition of Russia, political, social, and literary, there is very little in the book which will seem to exceed the bounds of reasonable liberty which are granted to writers of fiction.’’ Even within their pages, such novels were not presented as wholly fictional. In the preface to his novel Alexandra la Nihiliste (1880), Louis Noir, a prolific and best-selling author of adventure stories, declared that the fictional story of Alexandra was both “a true story” and “a romantic drama” — in other words, at once factual and fabricated.

The inside cover of Louis Noir’s novel Alexandra la Nihiliste, une martyre du tzar, 1880. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

When I first came across Jeanne Tilly’s story in the French National Archives, I was fascinated not only by the dimension of invented identity, but also by the fact that European newspapers were still writing about “nihilists” at all in 1906. The cultural touchstones of Russian nihilism—and as Abbott Gleason has pointed out, that label has always been nebulous —originate in the mid-nineteenth century, from characters like Bazarov in Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, the plot of Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s idiosyncratic novel What Is To Be Done?, and the writings of critics like Dmitri Pisarеv.

So why did these highly gendered images of Russian nihilism persist in Europe through to the year when Tilly committed her “imaginary crime”? It’s clear that the very term “nihilist” was essentially a fictional construct in this much later historical context. By 1906, the way in which Tilly’s actions made an increasingly imaginary construct real exemplified how changes in mass media—from newspapers to boulevard novels to wax museums—contributed to the blurring of boundaries between the real and the imaginary, with real-life consequences.