On September 23rd Schamma Schahadat, of the University of Tübingen, joined the Jordan Center for another talk with 19v, a working group on 19th century Russian culture. She discussed Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment in her talk, “The Difficulty Of Ending a Story: On the ‘Thick Novels.’”

She introduced her subject with Lawrence Sterne’s The Life and Opinion of Tristram Shandy (1968), whose narrator struggles to narrate. Details get in his way; his life and opinions distract him, and he can’t complete a sentence.

Where Sterne’s narrator struggles to begin, Schahadat contrasted, many Russian authors struggle to end. She described the structure of the novel: something is lacking at the center of the narrative. In Jane Austen’s works, for example, a husband. When the defect is found and fixed—Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy marry—the novel can end. Once the novel has ended, there is nothing more to tell.

“The production of narrative [...] is possible only within a logic of insufficiency, disequilibrium, and deferral”

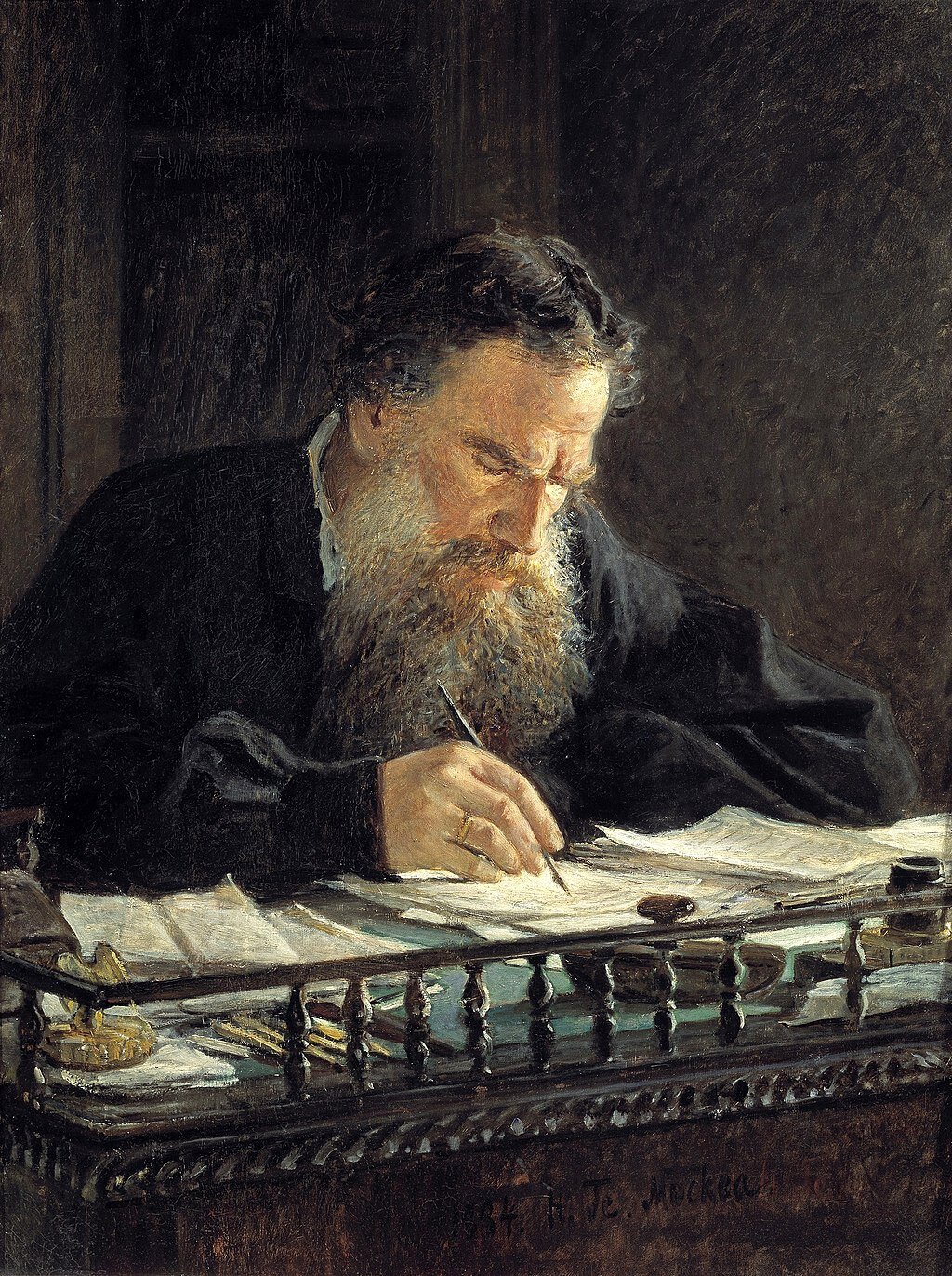

Unlike the novels of such traditions as the British and French, Schahadat pointed out, Russian novels in addition to depicting life regularly reflect on philosophical and religious questions. She examined War and Peace and Crime and Punishment as examples of Russian novels in which the ending is deferred. She explained that the Russia in which novelists like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were writing lacked a space for public discourse, and novels became that space.

In War and Peace, she argues that Tolstoy attempts to narrate the un-narratable in his War and Peace epilogue: the everyday time, chronos. In Crime and Punishment, on the other hand, Dostoevsky, she said, strives for closure, a super narrative of salvations.

The realist novel, she argued, is the answer to the romantic fragment. In Eugene Onegin, for example, Pushkin leaves his hero standing alone. He refuses to find closure. She asked how does a novel produce “the reality effect?” How does a novel pretend it is reality instead of language?

A consequence of of this relation to reality, she said, is the process of “deliterarisation” of literature—the thick novels refuse to end. She insisted, however, that aesthetics force its way back into the text, and novels will never manage to copy reality. They can never cover the whole, even though they try.

She explained that Tolstoy’s original text for War and Peace ended with a double wedding. His original goal was, in fact, to follow a Decembrist back to Russia with his family, but he pushed further and further into the past. The novel eventually ends with a 200-page epilogue that follows the nothing-ness of his characters’ domestic lives.

“This could be the topic of a new story--but our story now is finished”

On the other hand, the ending of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is really a new beginning, she said. He closes his narrative with a metaphysical opening that transcends historical time. Siberia, which is the first word of the epilogue, serves as a purgatory, she argued, leading the hero to a spiritual rebirth

Tolstoy and Dostoevsky try to depict the world as completely as possible. Tolstoy focuses on historical development, but his narrator gets lost when the story evades control. Dostoevsky looks to the future beyond the narrative.

During the Q&A, Schahadat discussed the relationship between serialization and the phenomenon of the never ending novel. She explained that Dostoevksy had to go on writing because he lived off the proceeds of his writing, but, she argued, many writers of thick books attempted to cover much independent of the need to be paid.

She also discussed “the problem of the middle,” how authors extend the middle enough to constitute a novel, in regards to novels like Oblomov and Idiot. She said in the case of Oblomov, the middle is subversive to the genre of the realist novel. Nothing happens in the idyllic scene, as in the epilogue of War and Peace. In Idiot, she asked why not a short story? She posited that it could be related to the question of serialization and Dostoevsky’s need to write.