This is the third in a series of posts organized by the North American Dostoevsky Society.

Kate Holland is an Associate Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Toronto. Her book, The Novel in the Age of Disintegration: Dostoevsky and the Problem of Genre in the 1870s, was published in 2013. She is a founding member of the North American Dostoevsky Society’s Reader’s Advisory Board and tweets on @fyodor76.

Before the #CP150 Twitter project, I was a Twitter lurker, but when I was offered the opportunity to join a group of international Dostoevsky scholars tweeting Crime and Punishment from Raskolnikov’s point of view, I could not resist the temptation. I teach the novel almost every year, in a Dostoevsky course, a survey, and a first-year seminar called “The Criminal Mind,” and this seemed like a great opportunity to look at it anew, and to go outside my scholarly comfort zone in the process.

I opted to tweet Part III, a key section of the novel. It includes Raskolnikov’s first meeting with the detective Porfiry Petrovich and the disclosure of his article “On Crime,” through which Dostoevsky reveals Raskolnikov’s “extraordinary man theory” for the first time. Here Dostoevsky seems to break with the ideas about Raskolnikov’s motives for the murder which he has been building throughout the first two sections of the novel and reveals the outlines of what ends up being his true motive. At the end of the section Raskolnikov begins to realize the nature of the “louse” that he has killed and the significance of his failure to take “the next step.” This section of the novel includes a lot of dialogue, some of which Raskolnikov is not present for, as well as a scene in which he is in a delirious state, which posed special challenges for the Twitter medium.

This Twitter project required three different modes of translation from the text: the most straightforward was direct transcription of Raskolnikov’s thoughts as conveyed by Dostoevsky and translated by Oliver Ready; the second mode was transposition of the text from third to first person in order to convey Raskolnikov’s thoughts as the context required; and the third was creative manipulation of the story by the addition of thoughts which might be conceivably ascribed to Raskolnikov. For a literary scholar like myself, fidelity to the text is second nature, thus the process of direct transcription posed no real problems. Transposition was also fairly easy; I am so used to teaching this text that I have an internal commentary on it in my mind which was easy to follow.

The hardest part to get used to was adaptation, or “filling in” gaps which the text intentionally leaves opaque. Given that this novel was first conceived of in the first person and contains many passages which can be seen as “stream of consciousness” avant-la-lettre, it is a rich environment to be mined for tweets. At the same time, though a novice to the Twitter form, I was also aware of the great gap between “stream of consciousness,” where thoughts are conveyed in as unfiltered a way as possible, and tweeting, which involves a whole series of formal and social filters.

My biggest quandary was how to treat the conversation between Raskolnikov and Porfiry. Although we had agreed that our collective approach to the tweeting should be broadly consistent, and that Raskolnikov should only tweet what would be practically possible (that is, he would not be able to tweet during a conversation, for instance), the extraordinary man theory is so central to the Crime and Punishment’s ideological structure that it seemed important to include it in our Twitter translation of the novel. Raskolnikov’s idea that extraordinary men can “step over” the law for the sake of a great idea is key to his process of self-realization, and there was no question in my mind that it had to be tweeted in order to give ideological and philosophical coherence to our project.

In this scene Raskolnikov’s tweets reflect his dialogue with Porfiry; he is presenting his ideas for a second time in the Twitter mode after they have been recited back to him by Porfiry with a new intonation. In the delirium scene at the end of Part III, it begins to dawn on Raskolnikov how far he has fallen short from the goal he set himself, how miserably his own squalid crime compares to the crimes of his hero Napoleon. Here I found that hashtags, one of the basic units of the Twitter toolkit, served to express his self-disgust quite appropriately in shorthand; I particularly liked#napoleoncomplex, #epicfail, and #lousenotnapoleon.

Our #CP150 Twitter project gave me a fresh perspective on Dostoevsky’s novel. The combination of the three modes of Twitter translation reminded me of the extraordinary complexity of Crime and Punishment’s narrative structure; I found myself constantly jumping between my three tasks as the narrative perspective moved in and out of Raskolnikov’s consciousness. It also revealed how much gets lost if we translate the novel entirely into Raskolnikov’s point of view and suggests some of the reasons why Dostoevsky may have rejected his original idea for first person narration in favor of a third person narrator. Here we lose Razumikhin as a moral counterweight to Raskolnikov, never guess at his burgeoning feelings for Dunya, and bypass Dunya and Pulkheria Alexandrovna’s response to their sudden meeting with Sonya. We are trapped instead in Raskolnikov’s monomania. While we trace the vacillations of his self-deception and self-revelation, those psychological developments are never embedded into a broader moral or social context.

Followers of @Rodiontweets will find themselves trapped in Raskolnikov’s perspective with no narrative respite. In this format the novel’s psychological claims emerge more clearly than its moral or ideological ones. In our Western cultural context this is perhaps quite appropriate, since the novel is best known for its psychological portrait of a criminal which influenced philosophers, writers and film directors from Nietzsche and Freud to Hitchcock and Cronenberg, rather than its moral and spiritual redemption narrative.

This is part 3 of a series of posts on the experience of creating @RodionTweets. You can follow the Twitter account here. The introduction to the series is here. Click here to read Part 2, or here to go on to Part 4. More information about the #CP150 project can be found here.

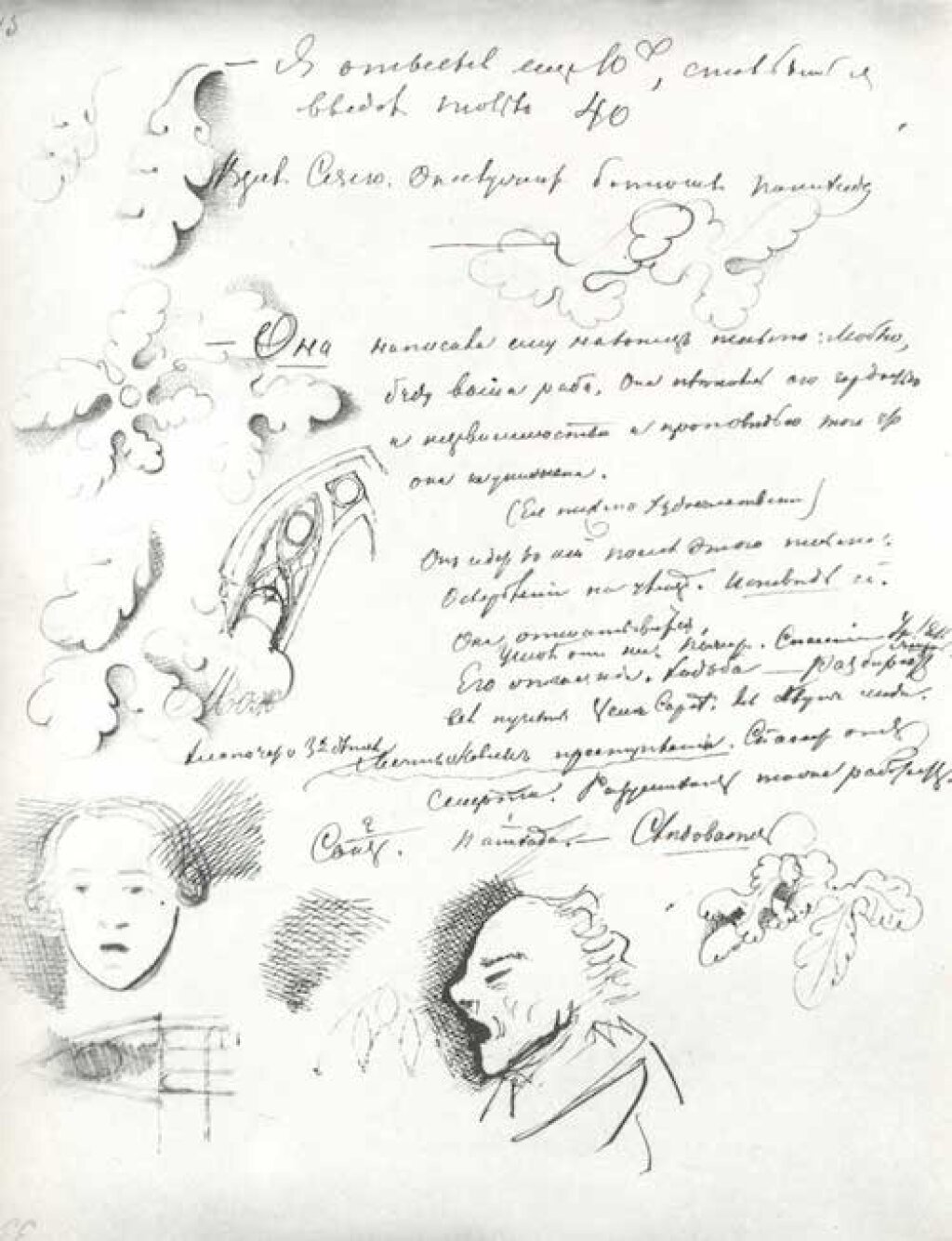

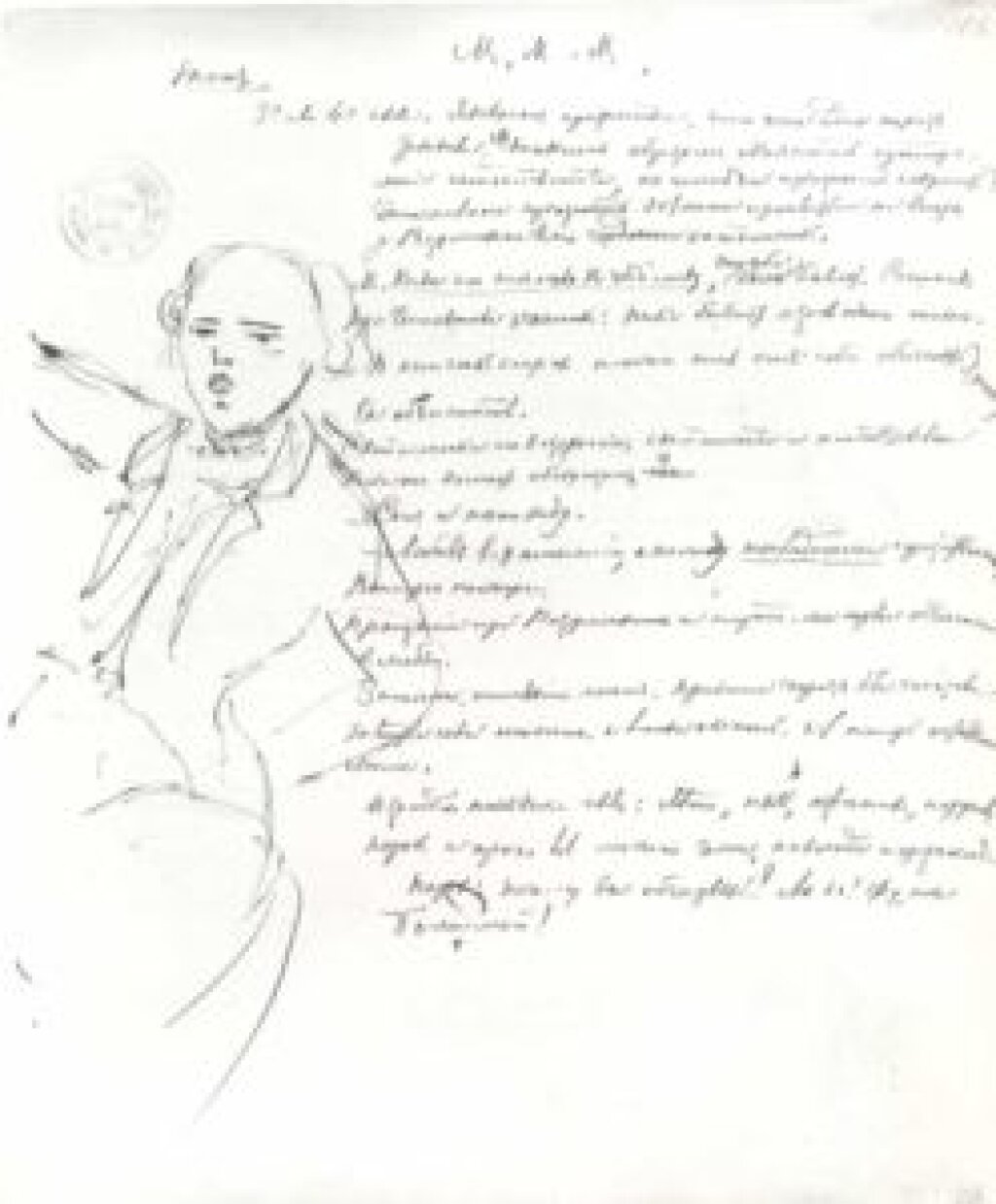

To learn more about the manuscript doodles pictured here, read the article on Open Culture here: Dostoevsky Draws Doodles. These images are borrowed from that post.