Is the war in Ukraine real? On the face of it, this is a remarkably stupid question. Thousands have died, over a million have been displaced, and European international relations have sunk into a morass. On a basic, human level, the war is tragically real.

Yet the question is relevant, at the very least as an homage to Jean Baudrillard, who, twenty-three years ago, published the provocative essay, “The Gulf War Did not Take Place.” Veterans would be hard-pressed to provide a polite response to a statement that appears to deny the reality of their experience, but the French theorist clearly had a different audience in mind. Baudrillard’s point was that, for the West, the Gulf War was a carefully-scripted media event whose plausibility relied on its adherence to the rules of simulation and propaganda.

But the war in Ukraine is not quite like the first Gulf War, which was asymmetrical in both firepower and media savvy. Like a Hollywood blockbuster, that war enjoyed a simultaneous, worldwide release: every screen was treated to the same images of the same smart bomb. This is not the case with Ukraine.

As the subject of constantly contested media narratives, the war in Ukraine has had a local reality that has somehow failed to take on a global scope. Science fiction writer Nancy Kress has a trilogy of novels positing an alien race that functions entirely according to “shared reality”—anyone or anything that contradicts it is declared “unreal” and possibly eradicated. By contrast, the global media (both old and new) have cobbled together a “shared unreality”, or perhaps multiple “unshared realities.”

I bring in science fiction deliberately, despite how irrelevant the genre might seem at first glance. Layered onto the senseless bloodshed and wholesale destruction are numerous fantasy scenarios that presumably have only the thinnest connection to actual events. Though I’ve written about some of them before, they are worth recalling here.

First, we have the fighting in Ukraine recast as a long-delayed sequel to World War II, with crypto-fascists emerging from their bunkers after seven decades of presumably cryogenic suspension. It’s like the scenario for Captain America, only with the Nazis on ice instead of the antifascist superhero. If this sounds flip (or, because of the American reference, irrelevant), it is anything but. The miraculous return of Nazis thanks to the miracles of mad science is a cliche of adventure fiction around the world (The Boys from Brazil, Hellboy), and Russia is no exception. One of the key players in the Ethnogenesis cycle, a sprawling, four-dozen-plus series of novels spanning continents and millennia, is the Fourth Reich, complete with a frozen Hitler in their antarctic Ultima Thule base.

Ethnogesis is an odd bird; in the attempt by pro-Kremlin media ideologue Konstantin Rykov to integrate the pseudoscientific ethnic theories of Lev Gumilev into popular entertainment, the authors inadvertently consign these widely-accepted, but profoundly crackpot ideas to what should be their natural habitat: low-rent science fiction. Yet the conflict in Ukraine seems tailor-made for an Ethnogenesis novel. The backwards-looking, black-and-white morality of official Russian propaganda transforms all of Russia’s international conflicts into a retread of World War II, the “Great Patriotic War” that still serves as the cornerstone of the national narrative.

Second comes the atrocity propaganda that veers dangerously close to blood libel: the widely-reported, and easily discredited story that Ukrainian fascists had crucified a three-year-old boy in front of his mother. It is not enough to fight fascists; now the enemy is downright satanic. Can a Ukrainian-born antichrist be far behind?

Finally, there is perhaps the most pernicious fantasy projected onto the Ukrainian conflict: the denial that the battleground itself has any geopolitical reality thanks to the wholesale dismissal of the very country as nonexistent. Putin has been quoted as repeating a common, condescending attitude toward the newly-independent state: “Ukraine not even a real country.” Sadly, even some of my fellow Slavists have come close to this line, in emphasizing the fundamentally divided nature of this hodgepodge of a country (“two Ukraines”).

Insisting on the fictiousness of Ukraine necessitates a strangely Romantic attitude toward the nation state. Are there really scholars (besides those infatuated with “ethnogenesis”) who argue with a straight face that a nation or a country is some kind of natural, organic entity? All nations are consensual fantasies. The denial of Ukrainian sovereignty breaks the laws of the fantasy genre by refusing to suspend disbelief.

Russian author and media persona Dmitry Bykov, who can always be relied on for a good turn of phrase, has called the battle for Ukraine a “writers’ war.” He is absolutely correct. It’s worth adding, though, that it’s a bad writers’ war (“bad” modifying not just “war”, but “writers”). In the Russian Federation, we have a largely unimaginative media apparatus that stirs up the public by invoking familiar cliches. In Eastern Ukraine, it’s far worse.

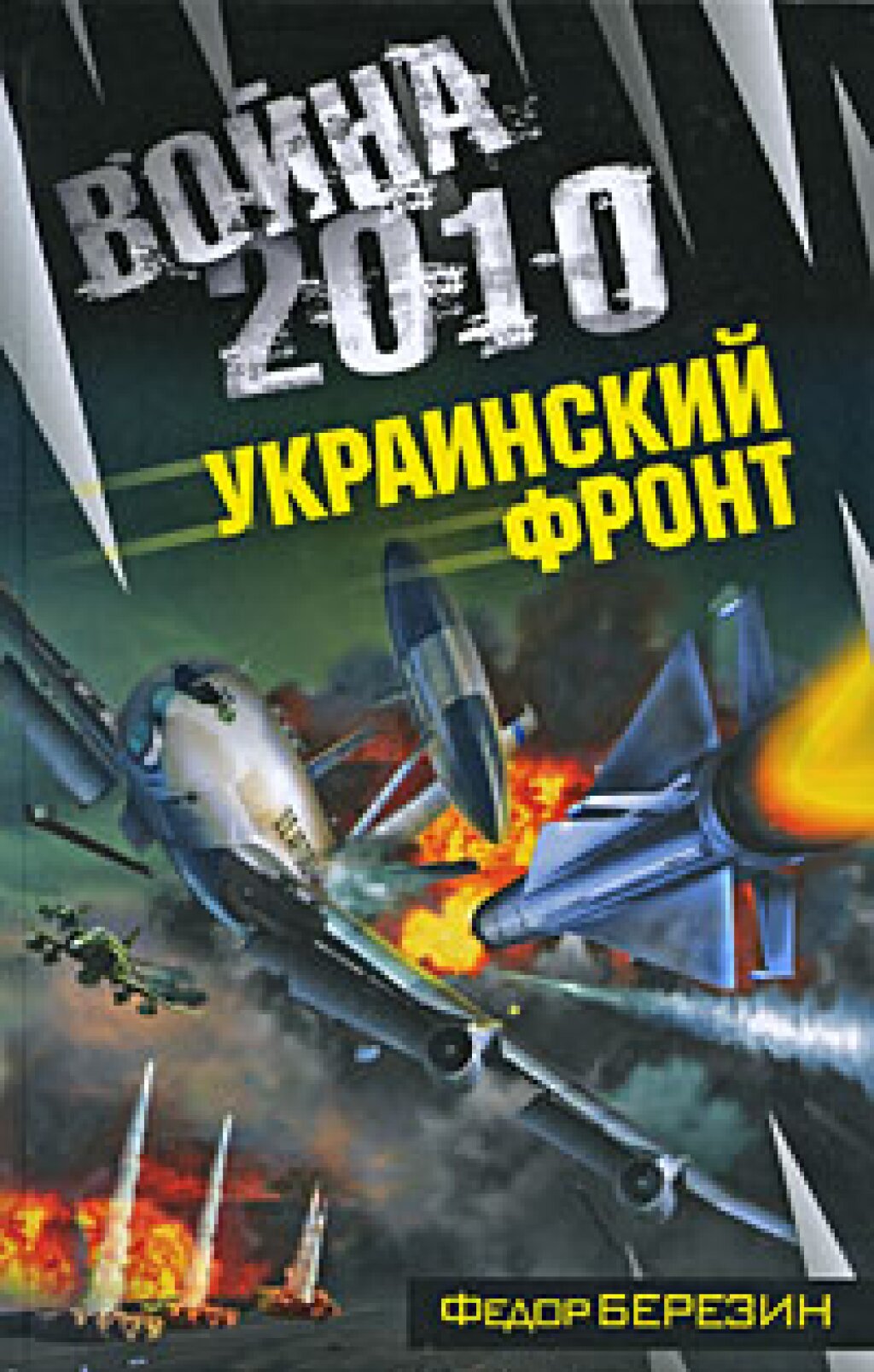

The leaders of the anti-Kiev faction include Igor Strelkov, previously known as an enthusiast for war reenactments. After years of playing soldier, he’s moved on to the real thing. And, of course, he’s joined by Fyodor Berezin, the author of military science fiction describing wars between Russia and Ukraine (and Russia and NATO over Ukraine) in several godawful books (including War 2010: The Ukrainian Front, whose cover illustrates this post.).. I’ve pushed my way through my fair share of subliterate potboilers over the years, but Berezin has proven a much more dangerous opponent on the page than he is on the battlefield: he has defeated my efforts to read him, hands down. World leaders may debate whether or not Russia is supplying the separatists with weapons, but the country’s traditions have definitely given Berezin its most powerful weapon in the literary arsenal: the terrible poetry that closes out each chapter.

Why should we be surprised when the facts of the Ukrainian bloodshed prove so malleable in the media? Pundits parse the difference between and “invasion” and an “incursion,” a distinction whose significance for international relations is directly proportional to its absurdity when it comes to the people on the ground.

As of this writing, all sides in the conflict seem to be observing a cease fire. It’s telling, though, that the American media, bored with possible peace, are immediately looking ahead to what may be an inevitable sequel (“How long will the cease fire hold? ” asks a breathless New York Times). The war in Ukraine used to straddle the odd boundary between the unthinkable (“How could Russia and Ukraine every really go to war with each other?”) and the foretold (as the object of cheap political fantasy since the Orange Revolution ten years back). Now it appears to be both.