Alexander Herbert is a PhD Candidate at Brandeis University focusing on environmentalism and youth culture in the late Soviet Union.

Punk arrived in Soviet Russia in 1978, spreading slowly at first through black market vinyl records and soon exploding into state-controlled performance halls, where authorities found the raucous youth movement easier to control. In fits and starts, the scene grew and flourished, always a step ahead of secret police and neo-Nazis, through glastnost, perestroika, and the end of the Cold War. Despite a few albums smuggled out of the country and released in Europe and the US, most Westerners had never heard of Russia's punk movement until Pussy Riot burst onto the international stage. My book, a history of Russian punk rock from the Soviet era to Pussy Riot, is technically an oral history — but it also includes several chapters written in journalistic style, expressing my personal opinion about things like punk in the provinces and Pussy Riot’s place in the scene.

As an aspiring academic historian obsessed with archives and narrative, I wondered whether oral history could be an adequate method to tell the story of Russian punk rock. As a long-time punk rocker myself, I struggle to ever accept an academic distillation of my own subculture. Ultimately, oral history ended up being the perfect genre for my purposes because it allowed the actors speak for themselves while letting me develop a coherent narrative. Besides, punk has an amazing tradition of oral histories.

The story began in 1978 Leningrad, when a few raucous youths managed to hear the Sex Pistols, Boom City Rats, and Ramones through illegally intercepted BBC Radio transmissions. Imagine hearing this music but having no idea what the musicians look like! Svin, Leningrad’s punk progenitor, led a gang of motley middle-class wannabes as they tried to emulate the style of “punk” as they understood it: raunchy, drunk, and disassociated from Soviet society. But the sounds they created diverged so fundamentally from traditional Russian rock that they were barred entry from the new KGB-endorsed Leningrad Rock Club. Only perestroika gave punk bands like Avtomaticheskie Udovletvoriteli and Obyekt Nasmeshek the opportunity to play in front of an actual audience. At this point, punk went as pop as possible thanks to the state’s reforms.

In this period, Russian punk music was rather light on substance. Aside from the rogue political punditry coming out of Siberia through Yegor Letov and his punk band Grazhdanskaya Oborona, punk in the capitals remained distinctly apolitical. Songs were about being drunk, dirty, and offensive — values distant from Soviet aesthetic ideals, to be sure, but certainly not anti-Party (and in some instances, Russian punk rock was even pro-state).

Then, the USSR collapsed and an ideological vacuum opened up. The 1990s saw the worst economic conditions for Russia in centuries and left many people searching for some kind of understanding of what was going on — a worldview. Some found it in environmental politics, pro-market democracy, anarchism, orthodox Leninism, or drugs. Others, unsurprisingly, found meaning in neo-Nazism and white supremacy. Suddenly, the kid you used to go to the Leningrad Rock Club with was sieg-heiling at punk shows and threatening to beat up punks who didn’t respect "Mother Russia." As this anecdote suggests, the 1990s witnessed a significant polarization of whatever punk scene existed in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The period also saw the beginning of commercial punk, particularly in Moscow, which forced new “Moscow Giants” like Distemper, Tarakany! and Naïve to choose sides between fascists and non-fascists.

Some things were still good, though. In St. Petersburg, an iconic new venue called Club TaMtAm carved out a space for strung-out amateur musicians and kids trying to escape their home. Moscow saw the opening of its own spaces, too—Jerry Rubin club for one, but more importantly, people's personal apartments. In the 1990s, a scene developed in Moscow around some charismatic anti-intellectual intellectuals who used music and poetry as their artistic medium. The “Formation” scene, or what I call “Intelligentsia Punk” became a phenomenon in its own right, developing in Moscow kitchens in parallel with the emergence of a wider urban punk scene.

By the early 2000s, a hardcore punk scene was still managing to maintain a modicum of independence from the literal boneheads that tried to infiltrate their shows. But these kids came from relatively well-off families that could afford flashy t-shirts and sweaters bearing the logos of Western bands. That kind of posturing and fashion hierarchy alienated some of the working-class kids, who recognized that they needed to form their own scene. The flashy hardcore kids, moreover, didn’t really do much to combat the threat of nationalism, preferring non-confrontation at the expense of the occasional beating and arbitrary violence toward innocent spectators.

Enter the anti-fascist movement. Moscow’s antifa solidified around a few influential individuals willing to provoke neo-Nazis to keep them out of their shows and spaces. Members of Moscow’s antifa headed out to provincial cities as a wolf pack, confronting fascists on the streets. Brawls ensued, with people dying on both sides. In one instance, an anti-fascist model was targeted because her photos were all over the internet. She was brutally stabbed, the blade missing her lungs by a mere inch.

Some band members brought weapons to shows to hand out to kids and imposed a buddy system for entering the metro. Things got so violent that the Russian state’s “Tsentr E” — the informal name for the Center for Combating Extremism — labeled both antifa and neo-Nazis "extremist groups." It didn’t take long for kids to catch on and realize that this scene was doing something more productive than investing their time and money into financing Western bands and labels. They were guaranteeing safe spaces for future generations and kicking hateful ideology out of the scene once and for all.

Antifa's interventions were successful — for the most part. Today, it's possible to go to Russian punk shows without running into a neo-Nazi or becoming the victim of violence. I wouldn’t say the scene is entirely safe, since the police still cause a stir once in a while, and fights definitely break out here and there, but these are not street bawls and are highly unlikely to involve fascists. Anti-fascism remains a major aspect of Russia’s punk scene, but even so, it’s common to hear the occasional homophobic or sexist remark. I don’t believe that the leftists saying these things are fully aware of what they are saying, but “I don’t like girl singers” definitely smacks of cultural arrogance and fear of a widening scene. Punk rockers worked hard to make the space safe from neo-Nazis; now, it's time to make it safe for anyone willing to participate.

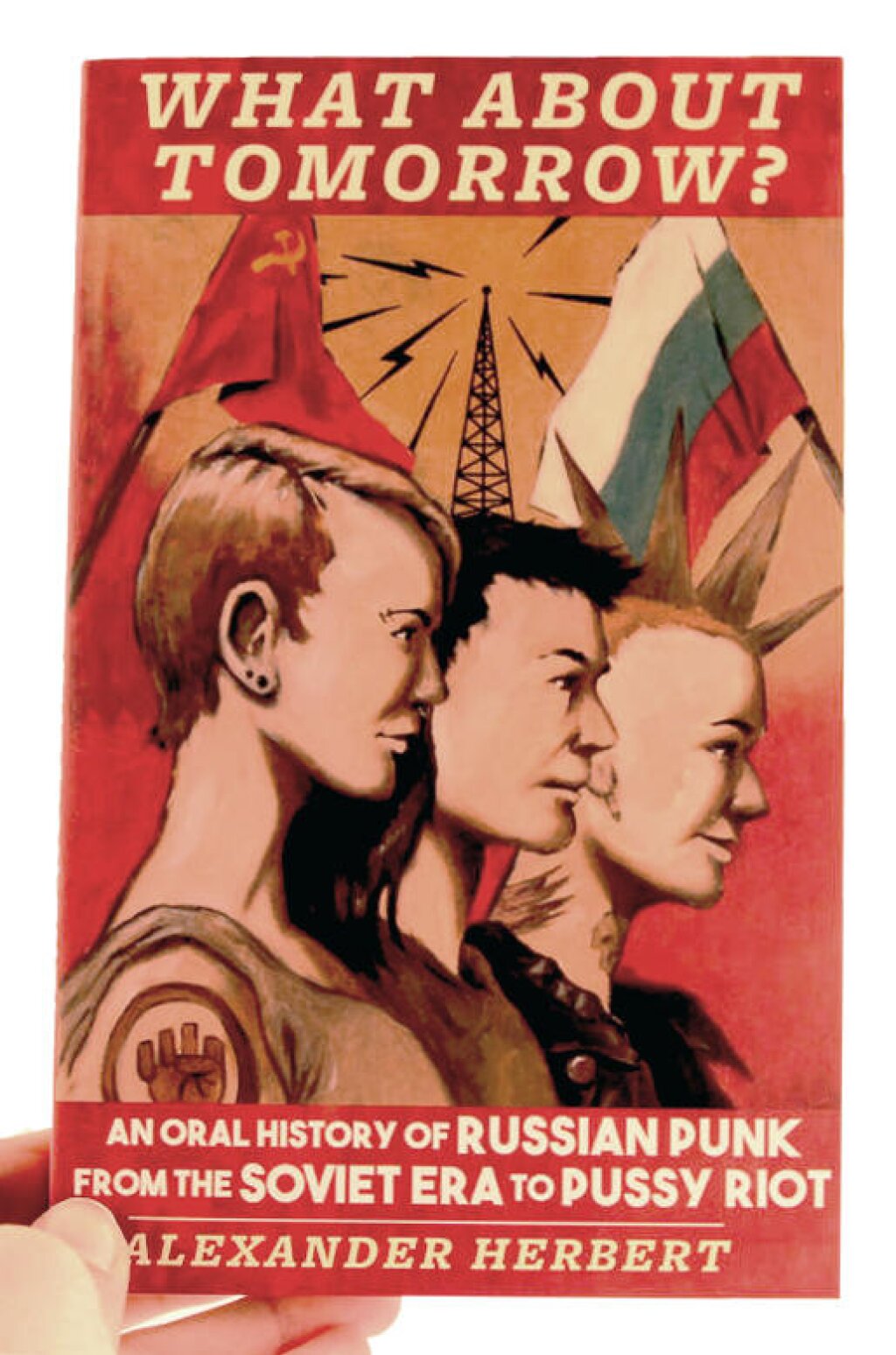

That’s the narrative in a nutshell. Being an informal oral history, my book makes no claim to completeness. I leave out many interesting stories, and provide little theoretical analysis of the anthropology of the scene, or the economics of DIY culture. Instead, I focus on the importance of space. The history of Russian punk is the story of kids growing up under a state that made them feel alienated and coming together to create, maintain, and expand a space where they can all actively turn that alienation into something beautiful. My book reminds punks (and even academics!) about the importance of space in making people feel like they belong, like they are wanted and empowered. No punk scene is perfect, and putting the entire span of one country’s punk history into 300 pages provides a bird's- eye view as well as a blueprint for future improvements. I believe wholeheartedly that some of the positive aspects of punk culture—straight edge, veganism, harm reduction, and outreach—are making giant strides in Russian culture today. Next time you’re in St. Petersburg, pay attention to how many employees at your local vegan restaurant are tattoo-clad hipsters. The book is called "What About Tomorrow?” because I want punks everywhere to recognize and improve what they have—make it the best you can, and do it yourself.