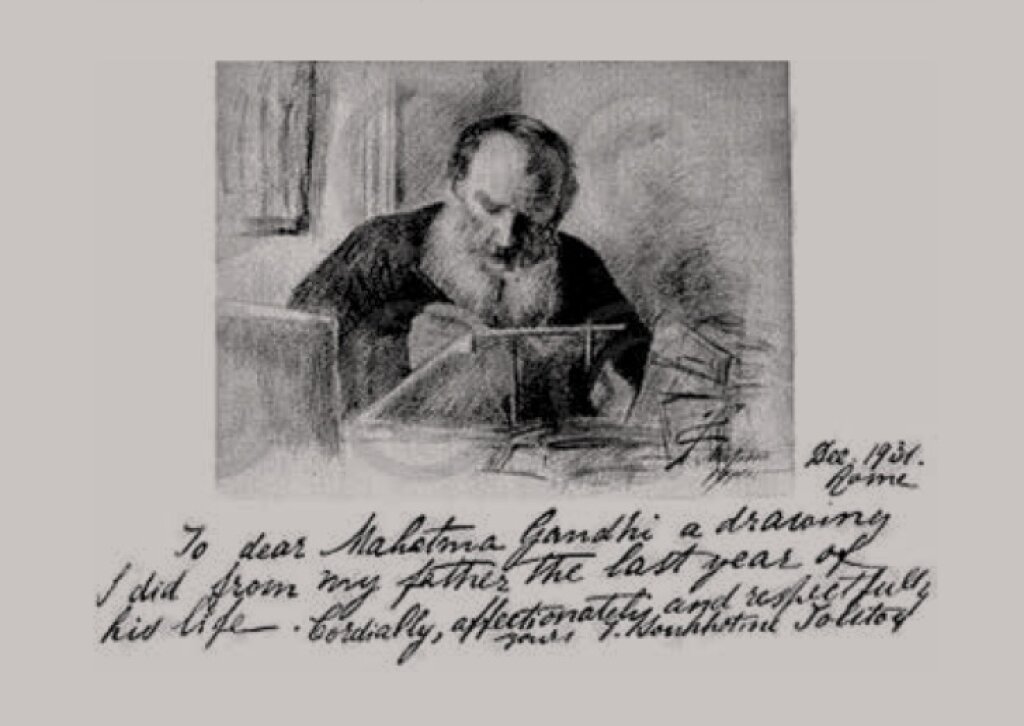

Above: A portrait of Tolstoy by his daughter, presented as a gift to Mahatma Gandhi during his visit in Rome in 1931. Source: https://youfrom.ru/2020/08/25/pismo-k-indusu/

This post features the third-prize entry in All the Russias' second Graduate Student Essay Competition.

Ruqaiyah Zarook is a graduate student in the XE program at New York University.

The Russian historian Nikolai Karamzin once said that for him, Kalidasa, the great classical Sanskrit playwright and dramatist, "is no less important than Homer.” The visionary Russian painter and philosopher Nicholas Roerich chose to live out his days in Naggar, India, leaving a broad and edifying artistic legacy. And perhaps most famously, Leo Tolstoy wrote to various revolutionary and literary Indian figures, from Mahatma Gandhi to Taraknath Das (to whom Tolstoy addressed his 1908 “Letter to a Hindu”) and the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. These anecdotes reveal a deep historical relationship between India and Russia that has not yet received the scholarly attention it deserves.

The historical links between Russia and India are numerous. The two countries have long enjoyed reciprocal artistic and cultural exchanges in literature, theater, and music. Beginning in the 1950s and until the end of the 1980s, the USSR dedicated significant funds to ensuring the availability of Russian texts in India — from children's classics and philosophical tracts to science textbooks and works of socio-political theory.

During the tense and taxing Cold War years, the USSR and India were able to uphold friendly relations with a distinct focus on artistic and cultural exchange, allowing each to deploy a form of soft power potentially more powerful and diplomatically penetrating than explicit political games. Just as Russian classics by Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Chekhov flooded Indian literary markets, Bollywood movies quickly became popular in Soviet Russia. Well-known actors like Raj Kapoor appeared in Hindi movies dubbed into Russian, enjoying a fascinating popularity among Muscovites (meanwhile, Indian literature and Russian films did not experience the same reciprocal resonance in Russia and India, respectively).

Following the declaration of Indian independence in 1947, the country's short supply of paper contributed to a great demand for books on math, science, and education. The Soviets were only too happy to fill this void. Translations of various Russian writers from Gorky to Pushkin to Tolstoy and Chekhov became commonplace. While English children’s books were relatively expensive in India at the time, Russian translations of these books were “absurdly cheap,” according to Gautam Ghose, program officer of Gorky Sadan, the Russian Cultural Centre in Calcutta. Per Ghose, Russian books gained popularity among Indian revolutionaries, who “carried with them Gorky’s Mother” and “a love for Communism" that "influenced the love for Russian literature." The writer Deepa Bhasthi noted:

"For a generation that came of age at the cusp of that very strange period in India when socialism ended and capitalism was becoming wholeheartedly embraced, these books remain a kind of sentimental paraphernalia. The world depicted in the Russian stories was an exotic one, far removed from the neighborhoods of South India, different in weather, names, food, and façades. But the affordable books made it a world its readers felt able to touch, to sense and know well."

Theater and music, too, enabled an ongoing program of cultural exchange between India and Russia. In 1914, for instance, the Pushkin Drama Theatre staged a version of Kalidasa’s play Shakuntala. This production faced aggressive resistance from the Russian Orthodox Church, which objected to placing an entertainment venue next to the seventeenth-century Church of St. John the Evangelist. The first stage play's origins in Hindu epic only amplified Orthodox clergy's concerns about the increasing sway of Eastern philosophies in Russia at the time. The actors and musicians performing in the play were Russian, but the music was composed by Hazrat Inayat Rehmat Khan, a Sufi and founder of the Sufi Order in 1914. “The Russians have a Western mind, but an Eastern soul,” Hazrat Khan is alleged to have said while in Moscow.

Despite the ROC's objections, Shakuntala was a success, helping inspire many other adaptations of Indian literary classics by Russian theater companies. The Moscow Children’s Theatre, for example, would go onto stage the Ramayana with Gennady Pechnikov in the titular role of Lord Rama. The same actor would later perform in Moscow for the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, in addition to being awarded the Padma Shri, India's fourth highest civilian award, in 2008.

Russian fascination with the Sanskrit language, and Sanskrit plays, reportedly began when linguist and writer Gerasim Lebedev went to India. After spending a decade there in the late eighteenth century and learning both Bengali and Tamil, the Russian scholar developed a profound interest in India’s classical literature. Hearing of Lebedev’s Indian sojourn, Tsar Alexander I later ordered a Sanskrit printing press to be established in St. Petersburg.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s led to the end of an era of robust cultural exchange between Russia and India, but lingering artifacts of this longstanding cultural affair still exist within literature, music, and theater, awaiting excavation by historians, literary scholars, and eager internationalists.