The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Mattingly Gerasimovich is a PhD candidate at Northwestern University studying Russian literature and film. In his free time, he co-hosts

and runs

, a nonprofit organization that works to promote creative writing and literary magazine education in high schools.

The period of New Economic Policy (NEP) in the early Soviet Union presents a fascinating field for film scholars to explore. After exiting the First World War and enduring a revolution and civil war—all within a few years—the newly-created socialist state faced a series of challenges and difficulties in consolidating state power from about 1921 to 1928. During this time, artists, writers, and political thinkers debated the role art would play in the new society. The complex relationship among directors, the government, and spectators in NEP-era film is thus a special case in the broader tensions afflicting early-Soviet politics and art.

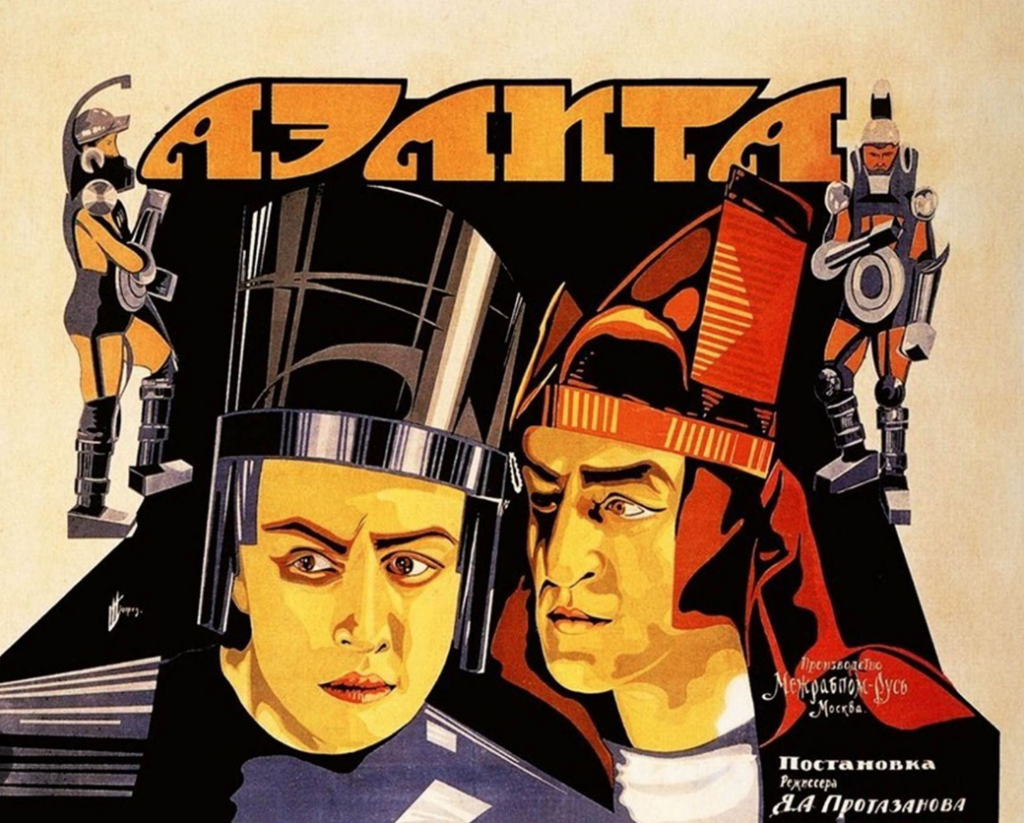

The case of film director Yakov Protazanov is illustrative. One of Russia’s most popular filmmakers before the Revolution, Protazanov left the country in 1920 to work for French and German-based film studios. The 1924 film Aelita represented the director's post-Revolutionary return to the domestic screen, and was his first film produced in the Soviet Union. Aelita encompassed nearly every major film genre—from melodrama and romance to sci-fi, action, and mystery—and, though it showcased few technological or narrative innovations, it enjoyed massive popularity at home and abroad. Protazanov’s return to the screen, despite his film's ideological imperfections, represented a net win for Party, which was able to demonstrate its ability to retain such a prominent filmmaker.

At first glance, Aelita's plot suggests that commitment to permanent revolution can engender political change on a cosmic scale. Protagonist Los (Nikolai Tseretelli), a Soviet engineer and proto-astronaut, is obsessed with Mars and travels to space with companion Gussev (Nikolai Batalov) after receiving the mysterious message “Anta Odeli Uta.” Once on Mars, the duo stirs up revolutionary fervor among the local slaves by telling them about the Soviet Revolution. The Martian queen, Aelita (Yuliya Solntseva), takes control of the revolt and deposes the king, but soon turns on the revolutionaries themselves. In the final scenes on Mars, Los kills Aelita. But then, in a twist, the viewer learns that "it was all a dream." Los' Martian adventures were a figment of his imagination, while the phrase “Anta Odeli Uta” derived from a tire ad he had seen earlier that day.

Despite its popularity, the film remained ideologically ambiguous and ended on what could be interpreted as a critical note. Engineer Los, who spent most of the movie in a daydream that comprised the plotline on Mars, returns to a reality saturated with advertising—a product of the limited reintroduction of private markets during NEP. Aelita projects those anxieties inward, contrasting Los' mundane waking life with his fantastical Martian sojourn. Aelita thus highlights the urgency of putting this "unconscious" drive toward permanent intergalactic revolution into practice.

Another potential problem with Aelita involved its lavish Constructivist aesthetics. Though the set and costumes were beautifully designed by Aleksandra Ekster, the world of the film did not reflect the rapidly changing socioeconomic situation of actual Soviet people. Moreover, from the standpoint of the Soviet film industry, the costs of creating film's like Protazanov’s on a regular basis would have been unsustainable in the long term.

One of Protazanov’s next films, His Call [Ego prizyv] (1925), took into consideration the realities of film production in the Soviet Union and attempted to satisfy both ideological demands and audience tastes and desires. Unlike the generically eclectic Aelita, His Call is closer to a traditional melodrama—a far cry not only from Protazanov's own previous work, but also from the radical experimentation of contemporaries like Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov.

Protazanov's hairpin aesthetic turn—achieved in less than a year—is certainly surprising. His Call strips down the visual opulence of Aelita into something much closer to the everyday. Rather than depicting the monarchy on Mars, Protazanov instead shows everyday Soviet people living their lives. The drama centers on Katya (Varvara Popova) and Vladimir Zaglobin (Anatolia Ktorov). Katya, the daughter of a factory worker (Mikhail Zharov) who died when she was just a child, becomes a successful worker like her father. Vladimir, the son of a former factory owner, returns to the Soviet Union from self-imposed exile in France to retrieve a box of treasure he and his father hid shortly before emigrating.

The relatively standard plot of His Call begins to reveal some of the limitations of cinematic experimentation. Films like Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, while massively influential on world cinema, did not appeal to the masses in the way that Protazanov’s pictures often did. Precisely because Protazanov's later films were less radical in form, they could legibly and unambiguously convey socialist content. The very title of his 1925 film refers to Lenin’s then-recent call to expand the membership of the Communist Party, highlighting Protazanov’s shift from émigré filmmaker to a true Soviet filmmaker.

Protazanov’s adaptation to emerging Soviet aesthetic and ideological standards informs our understanding of filmmaking in the later Soviet Union. After about 1932, Socialist Realist film used many of the methods Protazanov pioneered in the 1920s to decrease the ambiguity of its messaging. The simplicity and unequivocal ideological messaging of His Call, in particular, anticipate Socialist Realist conventions. Protazanov depicts wealthy émigrés as immoral criminals out of touch with the common people, no matter how much they may fundraise in order to "save the nation." The film's plot and aesthetics accordingly push viewers toward sympathizing with the young communist Katya over Vladimir, the violent thief.

The famously inconsistent and short-lived NEP period thus allowed filmmakers like Protazanov, who may not have flourished under the totalized aesthetic system that succeeded it, to adapt to the changing politics of the Soviet Union in real time. At the same time, Protazanov's shift to socialist melodrama created models for future films like Nikolai Ekk's A Road to Life (1931). In both cases, melodramatic elements help keep the film within recognizable, everyday bounds, allowing directors to fill the aesthetically and narratively neutral vessel with mobilizational socialist messaging. The result is a middle ground that should, theoretically, satisfy Soviet viewers and ideologues alike.

At the same time, Protazanov's turn away from radical aesthetic experimentation and ideological ambiguity demonstrates the importance of seemingly mundane factors like theater attendance to shaping directors' artistic commitments. Simply put, film messaging is more effective when more people see the film. The universal film language directors like Eisenstein sought to craft through montage and simultaneous viewings would have remained at a purely theoretical level without directors like Protazanov, who merged public taste with the dictates of Soviet ideology.