Felix R. Stetsenko is a first-year student at Amherst College. His previous Immigrant Story can be found here.

If the consequences of Hugh Everett’s “many-worlds” interpretation of Quantum Mechanics hold true, then, as Wikipedia states so eloquently, “everything that could possibly have happened in our past, but did not, has occurred in the past of some other universe or universes.” Perhaps, just maybe, in some alternate reality George W. never invaded Iraq or Afghanistan, instead pursuing some less calamitous adventure (Papua New Guinea, anyone?). In a more believable (though more jarring) universe, I could be dodging separatist bullets along with other Ukrainian Army conscripts in the shattered outskirts of Donetsk. Finally, with different (yet disconcertingly plausible) outcomes at either of two pivotal moments within living memory, I could be absent from this reality entirely.

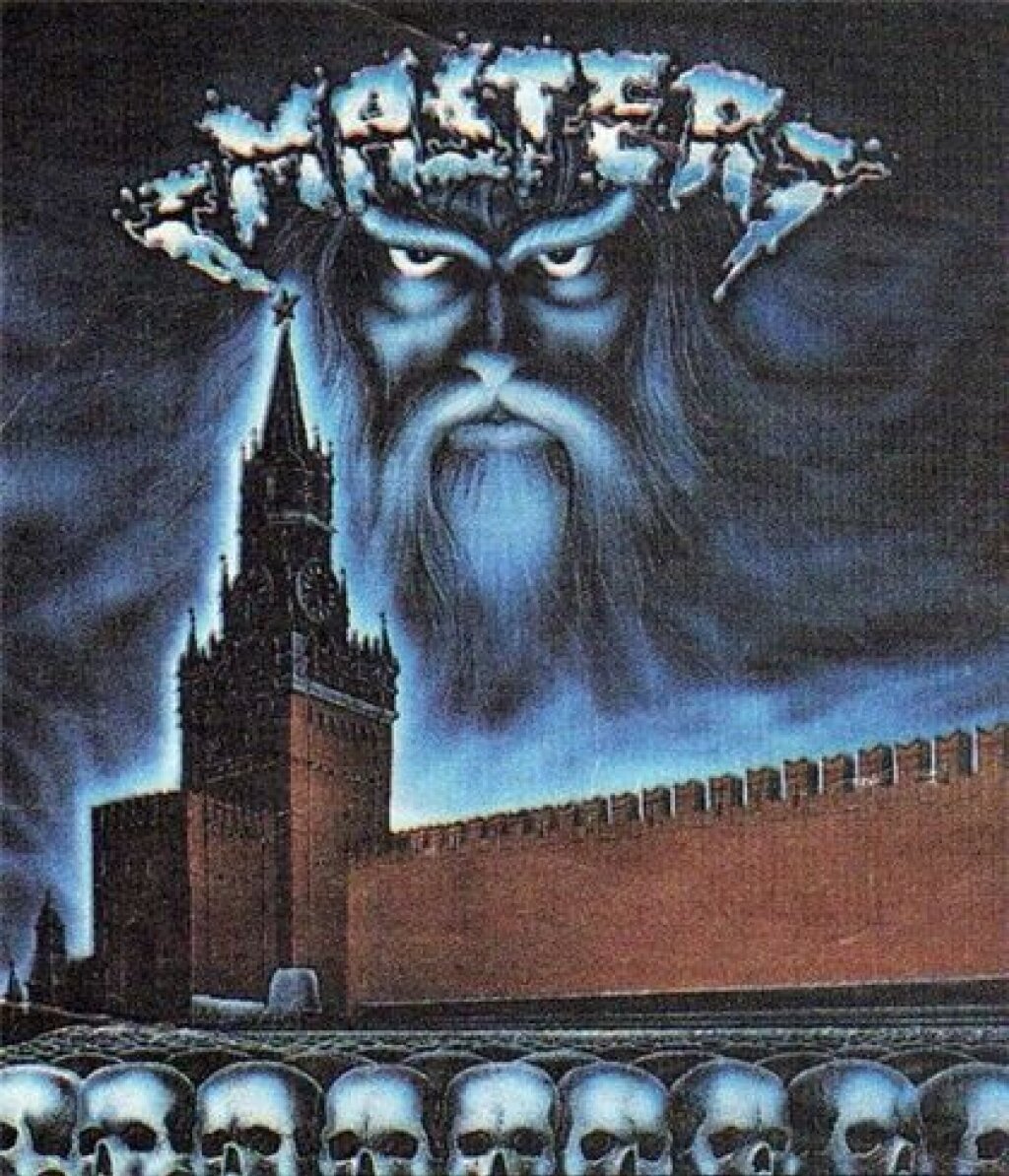

Instead in this universe, I’m writing this essay rather than hoisting a Kalashnikov for a simple reason (setting aside my innate discomfort with warfare): my parents’ determination to leave the Soviet Union. It may seem that leaving was an obvious path to take; however, in addition to parting with Communist dystopia, nuclear disaster, and prejudice, they were also forsaking relatives, friends, and anything that couldn’t squeeze into a couple suitcases en route to a freer existence in Haifa, Israel.

That my family could even encounter that fork in history is a testament to the independent thinking and intuition that has kept a certain botany professor alive to the ripe old age of 103. Seventy-four years ago, nobody saw the point of botany; her brother didn’t believe the rumors about children suffocating in one-way cattle cars, much less the whispers about their destination. But my great-grandmother paid heed, escaping the Nazi advance by fleeing into the eastern woods, where her ability to identify edible mushrooms – once whimsical – was suddenly crucial.

A half-century later, my mother and older brother found themselves in a gas-proof tent, crying at the sight of my father in a gas mask as he mechanically took to the impossible task of sealing the cracks beneath the doorways and windows with wet rags. Fortunately for them and for future me, their fears of Saddam Hussein using the chemical weapons which in 1991 he presumably possessed were not borne out. Instead, most of the (ironically, Soviet-made) SCUD missiles he fired at Haifa landed innocuously in the Mediterranean Sea. The guns of that war had barely fallen silent when a burst of serendipity (green cards awarded under a brand-new amendment to U.S. immigration law) finally brought my family to America. A few short years later, a pudgy baby with a fondness for building blocks found himself alive and content on a placid street in Florida, unperturbed save for the occasional hurricane.

I am here today because my wizened great-grandmother’s curiosity about the world’s most obscure wonders saved her from its ghastliest horrors, and because Soviet missiles had pretty bad guidance systems. My universe centers on a tranquil subtropical suburb, rather than a grim snowy battlefield, because my parents sacrificed the reality they knew for a chance at the unknown. I am here today, writing this essay, because it marks the path to empowerment: a chance to honor my forebears’ quest for a world in which the dignity of no human being is held hostage to fear or luck.