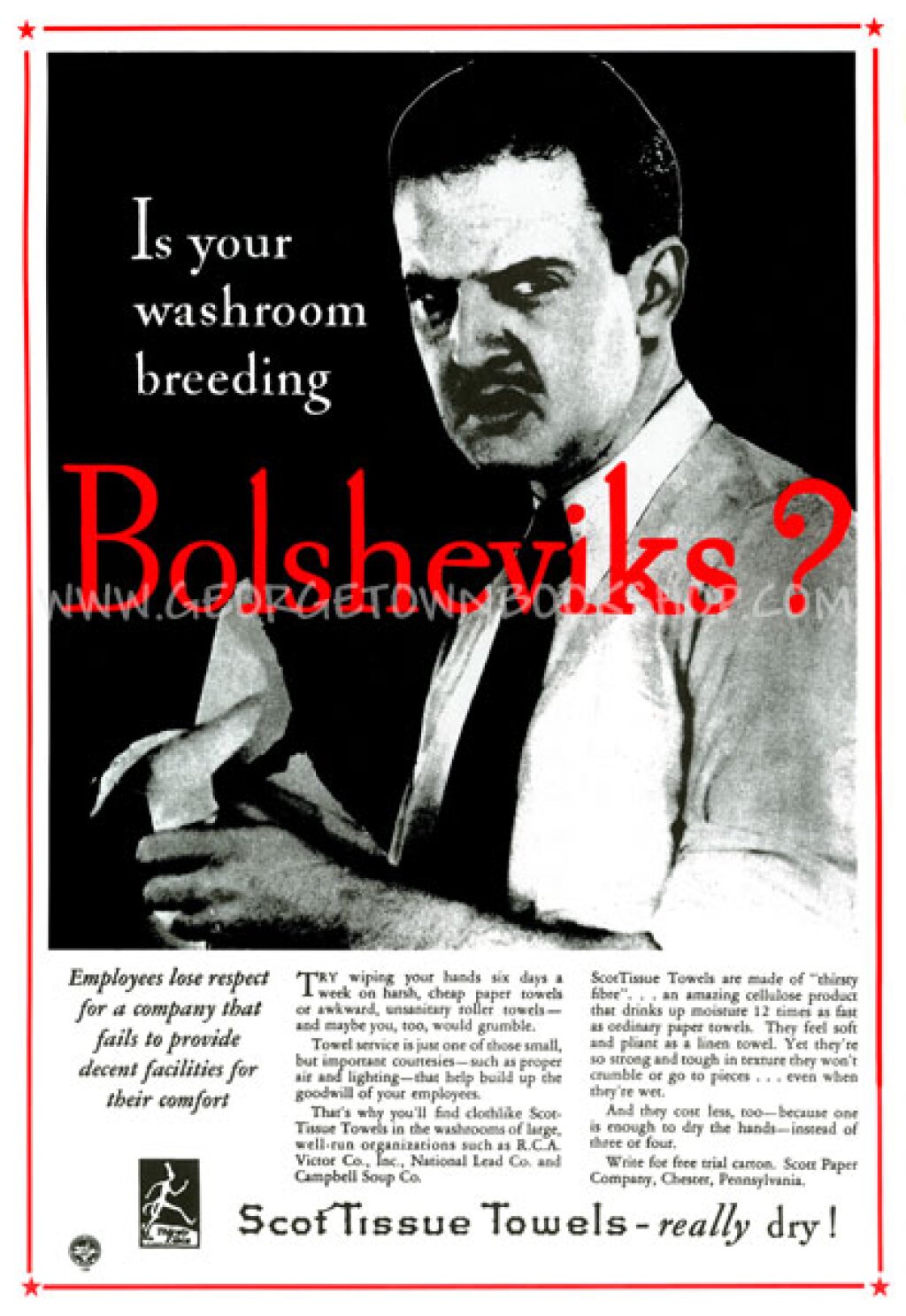

Above: Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) in 1974.

Svetlana Ostroverkhova is an M.A. student in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Washington specializing in the works of Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky. Previously, she studied at Moscow's Higher School of Economics and the Russian State University for the Humanities.

Russian literary historian Lyudmila Saraskina once noted that

readers worldwide intuitively match the scale of Solzhenitsyn’s personality and oeuvre with those of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky […], which means they see in him a man who changes the course of history.

For his own part, Solzhenitsyn stated that the three writers with the most defining and powerful influence on his work were Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Tolstoy. We know that he read Tolstoy's War and Peace at the age of ten, and that the novel spurred his decision to become a writer. He turned his attention to Dostoevsky at an older age, out of concern with ethical issues — which, Saraskina argues, Dostoevsky posits in a more resonant and modern way, with deeper meaning and prescience that Tolstoy. Accordingly, Dostoevsky's novel Demons (1871-2) earned mentions in Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel (1972) and Templeton (1973) lectures. Both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were spiritual mentors for Solzhenitsyn, albeit in different ways. If, from Tolstoy, he learned about narrative form and techniques of naturalistic realism, he was closer to Dostoevsky in his desire to show the moral, human side of the historical process. Many scholars and writers, including Solzhenitsyn, believed that Dostoevsky prophesied the rise of socialism and its astronomical cost to Russia.

Several researchers note traces of Dostoevsky’s legacy in Solzhenitsyn's works, dwelling especially on parallels between the authors' biographies and their uncanny physical resemblance. The first one to uncover these links was Vsevolod Lakshin, a member of the editorial board for Noviy Mir, who played a crucial role in publishing Solzhenitsyn’s One Day of Ivan Denisovich in 1962. Lakshin noted similarities between key dialogues within One Day and Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov (1879), which both include conversations between characters named Ivan and Alyosha on the topics of God and faith.

Solzhenitsyn's biography echoed Dostoevsky's from childhood on. Both men were raised in traditional Orthodox Christian families. Dostoevsky’s earliest reading materials were the Books of the Old and the New Testament, while Solzhenitsyn adopted his faith from his semiliterate, yet pious, grandparents. Both writers were educated in fields unrelated to literature, with Solzhenitsyn studying to become a mathematician, and Dostoevsky an engineer. Most famously, both spent several years in prison camps, their literary talent only unfurling in full after their respective returns to society.

It is a platitude that prison erases boundaries: aristocrats, peasants, laborers, and career criminals all live and work shoulder to shoulder (though “crime bosses” still force others to follow the rules of the criminal underworld). Their horrifying life experiences became treasure troves of characters for both writers. In prison, they faced fundamental questions of human existence. They learned that to survive as a human being under such circumstances — and not to sink into brutishness — was itself a heroic feat. However, in the words of Dostoevsky biographer Joseph Frank, “survival in this sense also meant a transvaluation of values, a process of purification by which the very meaning of life itself became transformed.”

Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn's incarceration resulted in two of world literature's best-known chronicles of prison life: Notes from the House of the Dead (1860-2) and The Gulag Archipelago (1973). Their time in the penal system significantly influenced both authors' politics, transforming them into fervent patriots and anti-revolutionaries. Following his release, Solzhenitsyn deeply regretted his earlier socialist ardor, writing in the 1970s that communism resembles a two-stage disease. After winning the first stage by attacking its victim like a wild beast and knocking them off their feet, it loses steam in the second stage when the victim realizes that they fell for an optical illusion and gains lifelong immunity against the sickness.

The two authors held similar views on the questions of guilt and responsibility for evil deeds. Rather than dividing people into categories like "guilty" and "innocent," they thought that fault rests with everyone without exception. During his court trial, Dmitri Karamazov says that “all share the guilt for all [vse za vsekh vinovaty]" and is ready to take on culpability for the other malefactors and endure punishment for their crimes. Elsewhere, the elder Zosima says to Dmitri:

If the crime of men turns you to resentment and overwhelming sorrow, even to a desire for revenge on the wrongdoers, fear that feeling most of all. Go at once and seek suffering for yourself [idi i ishchi sebe muk], as though you were yourself to blame for that evil deed. Accept that torture and bear it, and your heart will be soothed, and you will realize that you, too, are guilty.

Whereas Dostoevsky’s characters speak of universal evil, Solzhenitsyn is more specific, calling on Russians to take responsibility for Soviet-era terror — "all for all [vse — za vsyo]." In the words of Daniel Rancour-Laferrière, both writers believed that “better that everyone engage in the mild masochism of breast-beating than engage in sadistic revenge against real, specific criminals.”

Solzhenitsyn consistently defended this idea throughout The Gulag Archipelago, convinced that every single Soviet person was to blame for the decades of Stalinist terror. Even those who were not directly involved, he argued, were passive bystanders who turned a blind eye to the arbitrary injustices dispensed by the authorities. In the book's first volume, the unyielding patriarch Tikhon states in court that he acknowledges only those laws that do not contradict religious rules. At the conclusion of Tikhon's speech, Solzhenitsyn comments that “if everyone replied like this, our history would not be the same!” In the second volume, Anna Skripnikova presents another example of unconquerable will. Despite multiple arrests and spending decades in prison camps, she never apologized for her accusations against the Soviet authorities. “If everyone were at least one-fourth as brave as Anna, the history of Russia would be different,” Solzhenitsyn repeats.

The similarities readers have already uncovered between Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn's respective world-views pave the way toward further scholarship that would analyze the nineteenth-century author's continuing legacy in the work of one of his best-known successors.