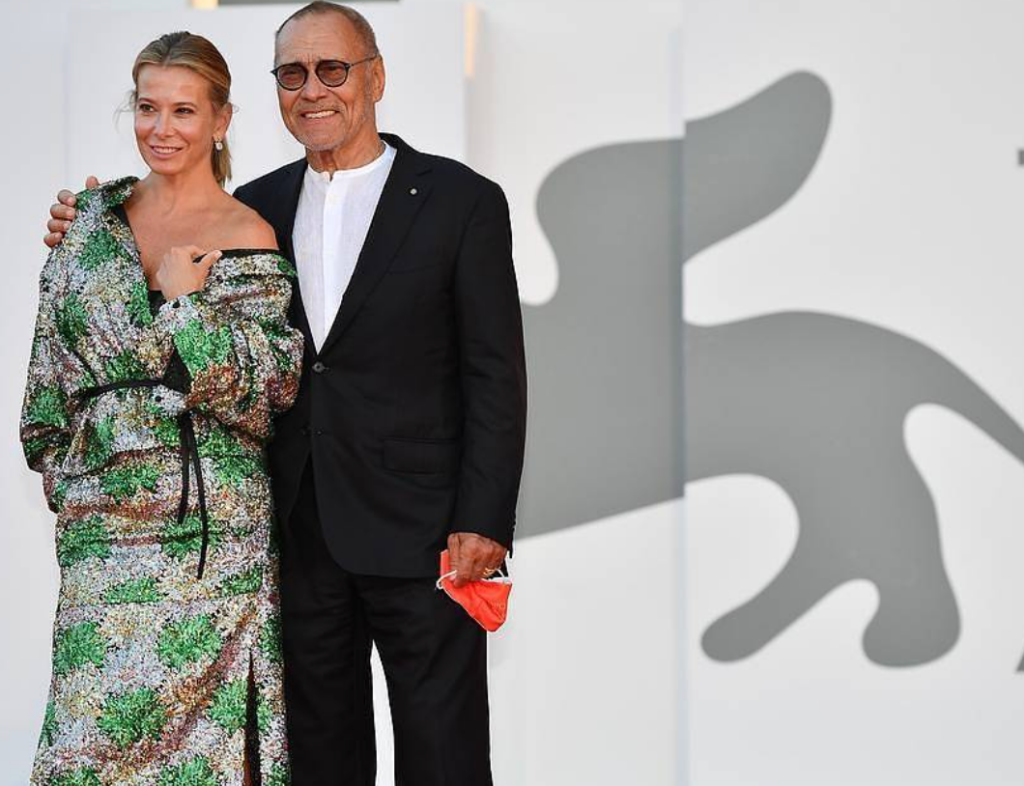

Above: Romanians protest in Bucharest against the Roșia Montană gold mine project, 2013

George Andrei is a PhD Student of Romanian and Environmental History at Indiana University, Bloomington.

“Sustainability” has become a buzzword in North America and Western Europe. From behemoths in the financial world to governments and administrative institutions, big money is, seemingly, finally making the move to acknowledging the world’s ecological and climate issues—even where their motivation may be connected primarily to sustaining profits. Behind the uplifting news of state afforestation projects, East Central Europe faces a hidden paradox: as foreign investors who already know the best shares to buy right now in the UK and EU funds increasingly sift for “sustainable” investments, internal political calls for development and foreign funds also demand large-scale infrastructural projects.

In Romania, the debate has taken shape beyond partisan politics, most recently within the USR-PLUS party. Fear of the ecological consequences of developmental projects has been in conflict with the perceived need for motorway construction and the revitalization of dilapidated rail infrastructure.

The matter goes beyond the political and the economic. Romania’s road safety record in 2020 was the worst in the EU, clocking in at 96 traffic-related deaths per million or nearly twice the EU average of 51. Infrastructural upgrades are especially important not only for reducing fatalities on the tightly packed and under-maintained national roads, but also for rerouting heavy traffic that currently has no choice but to pass through cities, villages, and other residential areas.

“Here rests the Moldovan highway,” reads the cross marking the burial spot of the one meter of highway built, and recently buried, in protest of the lack of progress. In the wake of demonstrations, scandals, and new stories that dramatically point out the failures of previous governments in building up infrastructure, Romanians increasingly hedged their bets with technocrats promising to build “real highways, not [ones only existing] on paper.” These projects promise a more complete integration with the EU market and the Schengen Zone, while also advocating for environmental protection: “both nature and infrastructure.”

History has not shown this combination to be easy to accomplish, with ample examples of the unintended consequences of development and environmental management drive. The most recent parliamentary elections returned a fractured legislature, in which the USR-PLUS party won only a minority position in a four-party coalition government headed by the PNL.

Romanians have become increasingly aware of their environmental difficulties. Today, news of deforestation is a regular part of the Romanian news cycle, and has become a hobbyhorse in the House of Deputies and the Senate. Moreover, an inflection point in environmental civic activism is playing an increasingly powerful role in Romanian politics. In 2013, Romanians protested en masse at home and abroad against a gold mining concession, the Roșia Montană Project in Alba County.

Roșia Montană proved that environmental questions can mobilize citizens across the political spectrum, reaching far beyond their immediate context. The Roșia Montană protests generated a framework for Romanian civil society to attract attention and stage political resistance to environmental degradation in the name of attracting foreign capital. This framework has most recently been effective in forcing government action over unsanctioned logging in the country, spurring action among conscious individuals through grassroots anti-logging efforts including apps to track illegal logging (albeit not without problems).

As investors, organizations, and governments at home and abroad call for massive projects to stimulate economic growth, how can they reconcile the inevitable fact that these projects will dramatically alter environments? Trees will be cut down, rivers bridged, and greenhouse gas emissions forced through exhaust pipes to make these developmental dreams a reality.

It is a difficult position to face. Foreign investments and their promises of further development are attractive and offer momentum to continue infrastructural projects. This is not to say that investment alone is enough to get the ball rolling. The inertia dampers of the precarious political situation and corruption in Romania serve as an opposing force that slows the momentum of such projects.

At the same time, historians like Brett Bennett have pointed to the expanding rift between notions of “nature” and economic “progress.” Increasingly, as “natural” environments become places of leisure rather than work, observers are beginning to suggest that we can make up for ecological destruction by sectioning off other areas into special preservation zones. It is easy to forget, historian Richard White reminds us, that, even when we are so detached from natural spaces, everyone is still connected to these environments through our everyday lives. We also impact them through our work. What difference does it make for levels of carbon sequestration whether trees are felled by illicit logging or to make way for the expansion of the A1 motorway?

So long as the growth of the Romanian economy continues to depend on both EU economic and infrastructural integration, the calls, and external funding, for grand infrastructural projects will continue. The hope that developmental projects represent will continue to drive political and social pressures on Romanian environments: in the words of deputy Iulian Bulai (USR-PLUS): “Biodiversity is important. Dragonflies, frogs, beetles, water lilies, field mice and spiders are important. But not more important than HUMANS.”

Activists supporting the two issues have worked together to oust governments they saw as corrupt or inefficient in pursuing their respective interests. As new sums are being allocated toward these inherently competing concerns, it is likely that this debate will continue to simmer, building pressure in Romanian politics and civil society.

There is no obvious compromise between these competing agendas. Immense benefits could result from infrastructural projects and the economic opportunities they represent, including funding for reforestation initiatives and environmental protection. It is one thing, however, to oppose open-pit mines like those at Roșia Montană, and another to critique seemingly less pernicious and even desired projects. With such initiatives, it is even more important to evaluate environmental costs just as seriously, critically, and consciously as the economic benefits. These must not be obfuscated in the name of development.