This is Part II in a two-part series. Part I may be found here.

Yaraslava Ananka is a research assistant at the Department of Slavonic Studies of the Humboldt University (Berlin, Germany).

In parallel to the diversions enacted against Russian media propaganda, another guerrilla appears on the literary front. The fate of the clip's protagonist amalgamates several intertextual biographies of various Catherines. The most important intertext of Katia-Vatnitsa is Taras Shevchenko's poem Katerina (1840), which begins with the (already) idiomatic warning to all female Ukrainians: “Love each other, you, the black-browed,/ But don’t love the Muscovites.”

Shevchenko’s Katerina falls in love with a Russian soldier and becomes pregnant. Stigmatized by an extramarital affair with a stranger — a Russian no less — Katerina is expelled by her own family, thrown out of both her home and her village. She returns to Moscow to look for the father of her baby. On the way, Katerina meets his regiment, but the soldiers mock her, and her lover publicly rejects his fatherhood.

The Katia in the clip also falls in love with a Muscovite — Putin, the “green little man." The video stages this Katerina’s dramatic meeting with Russian soldiers as an orgy of dolls with plastic toy soldiers (1:22–1:31). Unlike in Shevchenko’s poem, the Crimean Katia is demonstratively denied the author’s empathy and portrayed as a prostitute and a traitor. She dances and copulates with the soldiers, tramples on both the yellow-blue flag of the European Union and the Ukrainian flag, drinks vodka, and enjoys herself at the Sevastopol military parade. The debauch also unfolds at the intertextual level:

Didn’t we sing “Ked’ my pryjšla” together?

Who adjusted your drawbar, my dear?

Didn’t we, didn’t we, my dear?

Oh you, Katia, my Katia, you fat-faced?

(2:20–2:31´)

The intertextual bacchanalia culminates with allusions to another — this time a Russian — predecessor Catherine. In Aleksander Blok’s Poem The Twelve (1918), “She has leaned back her face./ Her teeth shine like pearls... / Oh, you, Katia, my Katia, / You fat-faced...”

Via Blok, the clip draws a parallel between the annexation of Crimea and the hysterical, euphoric independence referendum that followed with the excesses of revolutionary turmoil in 1917. The quote refers to a passage in Blok’s poem describing an affair between the soldier Van’ka and the prostitute Kat’ka, who is known to have slept with Imperial officers and junkers. Kat’ka is always with those who have money, power, and weapons. Thus, the clip realizes the Russian swear word bliad’ (whore) in the parasitic and automatically-idiomatic interjection that replaces Katia’s speech. Pro-Russian "hurray patriotism" is recoded as "whore patriotism."

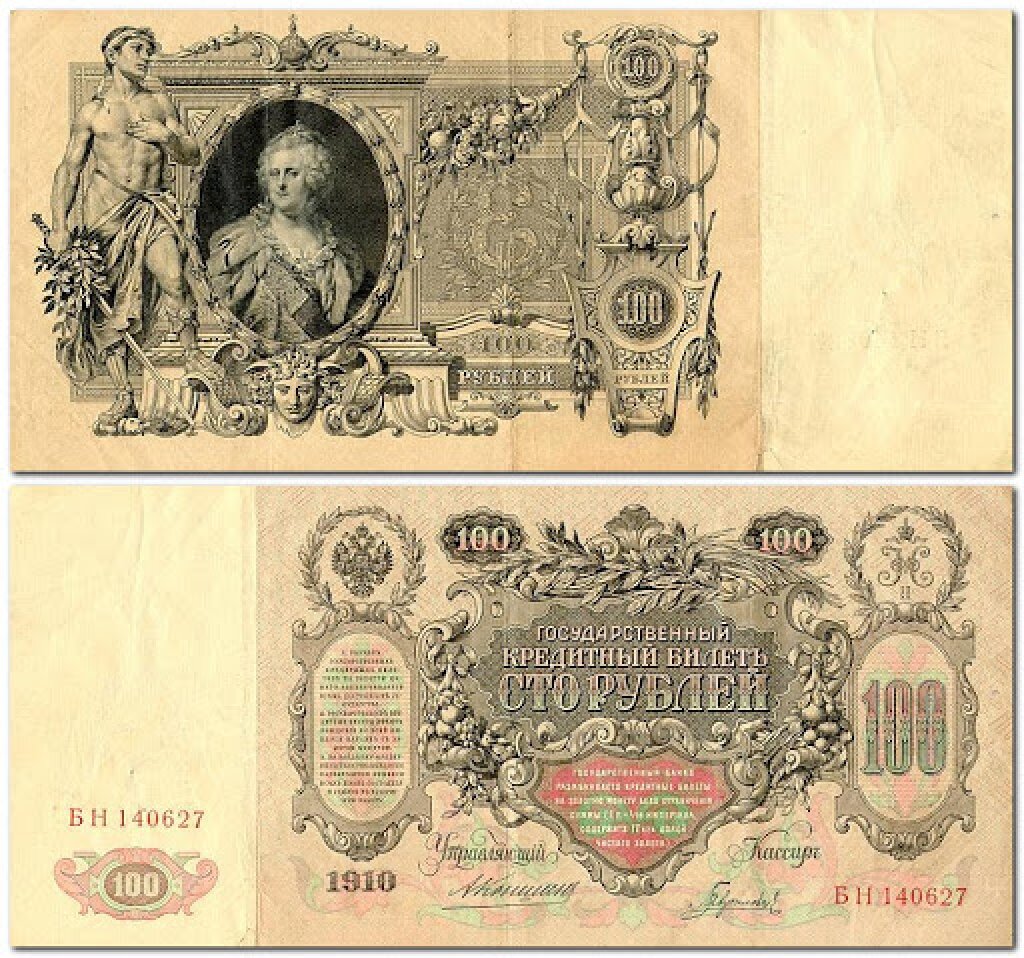

In Blok’s poem, the name Kat’ka has further connotations, namely financial and economic ones. In pre-revolutionary Russia, a 100-ruble note with the image of Catherine the Great was called a kat’ka.

The full implications of this Catherine would not be complete without anecdotal references to the sexual excesses of the eponymous Empress, Catherine the Second, with the Guardsmen and her favorites — the most prominent among them being the “Crimean Superior,” Prince Potemkin.

The clip is merciless in its linking-together of historical and current political events and anecdotes, even to the point of obsession. The video even alludes to an apocryphal account of Catherine the Great's death, which claims that she died trying to have sexual intercourse with a horse. The legend is old, but for the generation to which the clip's creators belong, it was updated visually and cinematographically by the German porn film Catherine and her Wild Stallions, shown during Perestroika in the video salons of the decaying USSR. The clip visualizes some parts of this rumor. At the end of the video, we see a stage with a poster reading CRIMEA IS UKRAINE. In the background, all the defeated dolls and soldiers lie dead; the only rider left alive flies the Crimean Tatar flag as his horse rapes a dead Russian soldier (5:23–5:35).

Ultimately, the clip cites another Catherinic identity, this time a quotation from the song Katiusha (1938): “Apple and pear trees bloomed, / Fog clouds floated over the river. / Katyuisha went out on a shore, / On a high, steep shore.” In the clip (1:06-1:23), the words are transformed: “Pear and apple trees bloomed in her soul. / Drink vodka to the grandfathers and to the victory!”

In the original song, Katiusha goes out on the shore, which for the purposes of the clip is the Crimean one. The song was so popular in the late 1930s that a mobile rocket launcher was even named “Katiusha” in its honor. "Katiusha" belongs to the Soviet emblem of victory, an important fact for our clip, which dismantles several mnemotopics of the Great Patriotic War.

In terms of intertexts, the clip insists on Katia's dissociative identity disorder. She has several literary biographies that collide and compete with one another. But what unites them all is Katia’s narrative end. In Shevchenko’s poem, Katia kills herself because her lover betrayed her. In Blok’s poem, she is killed by her lover. In pornographic legend, Catherine the Great dies during a semi-ritual copulation with her animal lover and symbol of power, a horse. And only in the Soviet song that gave its name to the artillery vehicle has Katiusha herself become a deadly weapon.

Despite its meta- and multimediality, the video is deeply literature-centric. It proceeds from various Catherinic subtexts that collectively state that Katia’s death is literarily preprogrammed. The intertextual fatality oppresses her. The clip enforces this omen.

Katia-Vatnitsa dies twice. The first time, her own death curse activates. In the video, a poster with the sentence “Even if stones fall from the skies, we are in our homeland” flashes (3:49´). The sentence points to the biblical Book of Joshua. There, however, God throws stones on Israel’s enemies. Notably, even this demonstratively blasphemous poster is not an invention, but the text of a real patriotic Russian billboard displayed in Crimea. The clip takes the poster at its word. Like Christ Pantokrator, like God himself, Orest Liutyi buries Katia and her soldiers beneath pebbles from the Black Sea (3:47–3:55´).

The second time, Katia is executed by the poet himself, Orest Liutyi’s co-author Artem Poležaka. It is he who dances in a mask, a dog skull grinning on his chest, as he bites off Katia’s head at the end of the clip (5:15–5:19´). Here, we see the culmination of analogy magic. Whereas vandalism is programmatically collective and anonymous, voodoo performance requires a priest: an authorial actor and director of the ritual.

The rhetorical question at the beginning of the clip — that is, whether Katia is obsessed — receives a clear answer: Yes — with linguistic and pictorial discursive demons. However, the video practices meta-medial and intertextual exorcisms that do not work. Crimean Katia is rejected and alienated, fighting against strangers even up to the eschatological battle prophesied at the end of the clip.

This salvation-historical Happy End presupposes a violent mimesis whose vicious circle cannot be broken — at least, not by means of such a mimetic medium as video.