Sami Suodenjoki is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre of Excellence in the History of Experiences (HEX) at Tampere University and a visiting scholar at the Centre for Political History at the University of Antwerp. The text below builds on his article “Popular Songs as Vehicles for Political Imagination: The Russian Revolutions and the Finnish Civil War in Finnish Song Pamphlets, 1917-1918,” published in Ab Imperio 2/2019.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 left a deep imprint on popular culture across and beyond the collapsing empire. Popular songs, circulated in printed form, were among the first media to tackle the transfers of power as well as the characters of revolutionaries and tsarist authorities.

In the Grand Duchy of Finland, one of the empire's Western borderlands, the February Revolution was a particular inspiration for songwriters. Just a few weeks following Nicholas II's abdication, the first song pamphlets addressing revolutionary events hit the market. These pamphlets continued the long European tradition of broadsides, cheap ephemera typically produced by and for lower-class people.

Three reasons made the February Revolution an especially fruitful topic for song pamphleteers. First, the revolution ended tsarist censorship in Finland, allowing songwriters to freely discuss political affairs and mock the authorities. Second, the dramatic surge of revolutionary events offered ideal material for topical verses that relied on melodrama and sensation. Third, the revolutionary situation produced an explosion in the number of public events, which in turn provided an extensive market for selling song pamphlets, as well as venues for performing the songs themselves.

The revolutionary atmosphere was reflected in the frequent mention of public figures in popular songs published in 1917 and 1918. Nicholas II, the Empress Alexandra, and Rasputin featured as dominant anti-heroes in these songs, just as they did in contemporary Russian popular culture.

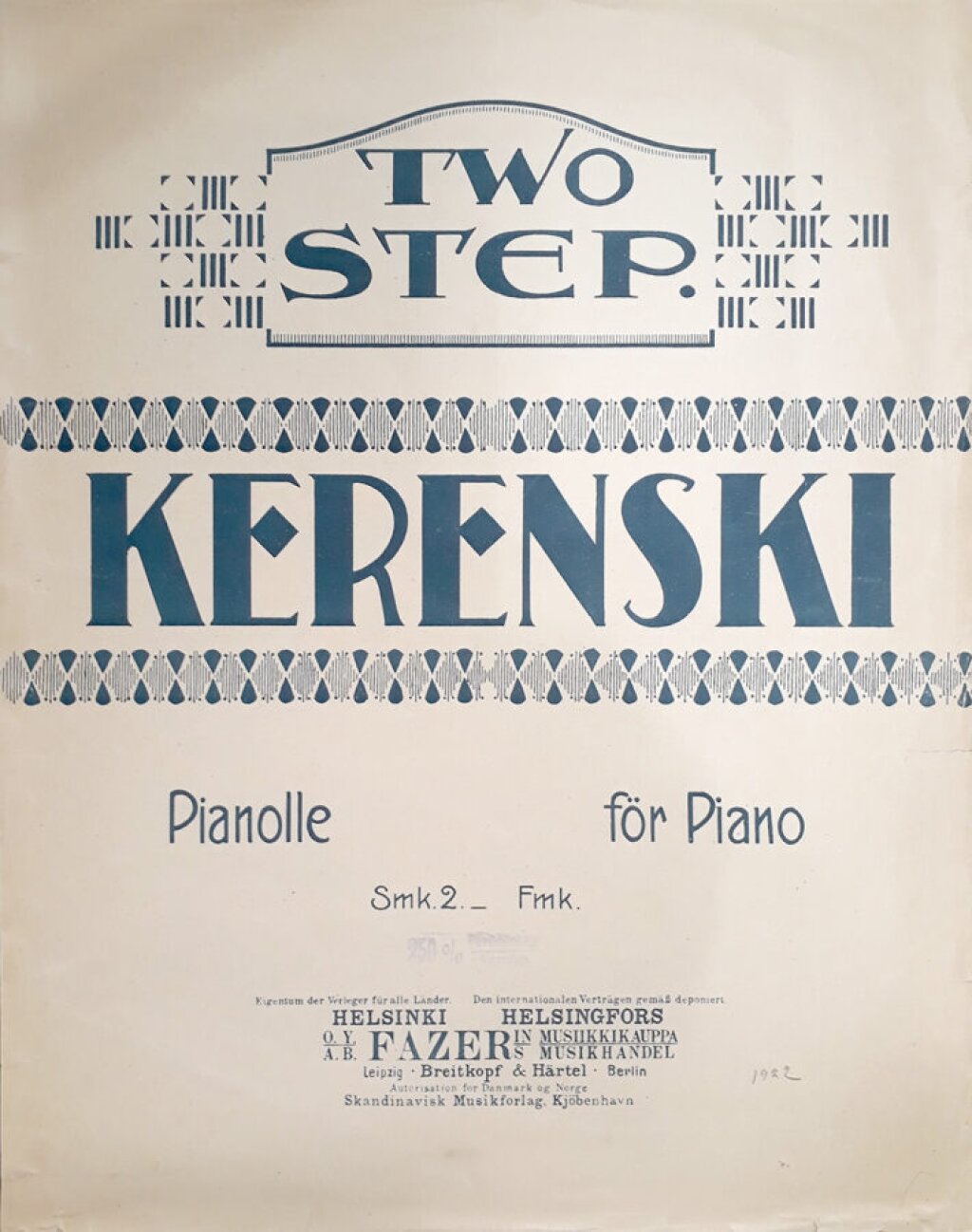

The song pamphlets also demonstrate good knowledge of top imperial officials, who were depicted as ruthless oppressors deserving their own downfall and as well as prosecution at the hands of the revolutionary regime. Of the new revolutionary Russian government, the songs highlight only Alexander Kerensky, who tended to be demonized because of his decision to dissolve the Finnish parliament in the summer of 1917.

Compared to their enthusiasm for the February Revolution, Finnish popular songs devoted far less attention to the Bolshevik Revolution in October. In the fall of 2017, Russian political dynamics were affecting songwriters' imaginations only indirectly, through the radicalization of political rhetoric within the Finnish socialist leadership and press. These effects, in turn, translated into more militant texts distributed by song pamphleteers.

The events of the Finnish Civil War, a byproduct of the October Revolution, became a key inspiration for popular songwriters in early 1918. Some songs from the Civil War period sympathized with Finnish Red revolutionaries. Others tapped into the mainline of White propaganda, emphasizing the close connections among Finnish Reds, Russian soldiers, and the Bolshevik leadership.

After the Red revolutionaries had lost the Civil War in late spring 1918, Finnish authorities stemmed the tide of political song pamphlets. This action attended the return of censorship and new obstacles to working-class cultural activity. Some of the most active song pamphleteers ended up in prison camps, suspected of aiding and abetting treason.

Regardless, in the ensuing years, the Russian Revolution continued to inspire Finnish popular songwriters. Unlike the ephemeral songs popularized in 1917-18, several of the later numbers went on to become trans-generational hits.

One Russian-Revolution-themed song that remains well-known in Finland today is “Kerenski,” which borrows its tune from the popular Russian two-step dance “Karapet.” “Kerenski” became a dance-floor hit across Finland in 1919, and was recorded numerous times in the decades that followed. The song's popularity derives from its caustic mockery of Alexander Kerensky as a “cook” who tried to “bake” a new Russia by using various nationalities as ingredients — all before fleeing abroad at the end of 1917.

Another example of the Russian Revolution's longstanding appeal in Finnish popular music is “Vapaa Venäjä” or "Free Russia." This song may have originated among Finnish Red refugees, who fled to Soviet Russia in the aftermath of the Finnish Civil War. "Free Russia"'s melody was based on the famous Russian patriotic march Farewell of Slavianka, but the Finnish lyrics addressed the end of an oppressive era and the creation of a new Workers’ Russia.

"Free Russia's" transformation into a popular music hit was distinctively transnational and would have been impossible without the rise of the international recording industry. Migration brought the song to North America, where Finnish immigrant tenor Otto Pyykkönen recorded it (with alternative Finnish lyrics) for Columbia Records in 1924. In the years that followed, the march also achieved fame in Finland as a fixture at workers’ meetings and demonstrations.

In newly independent Finland, bourgeois and even Social-Democratic newspapers labelled "Free Russia" an unpatriotic rhapsody of the Soviet regime. However, Finnish Communists embraced the march as offering a counter-image to both Imperial Russia and the oppressive nation-state in which they currently lived. What made "Free Russia" different from many song pamphlets of 1917 was that it located an imaginary workers’ paradise not in Finland, but in Russia.

The imaginary "Free Russia" eventually became a reality for thousands of Finnish and Finnish-American Communists, who fled political discrimination and depression to the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and early 1930s. These expatriates included Emil Rautiainen, author of the first recorded version of "Free Russia," and Jukka Ahti, who performed the more famous version of 1929. Ultimately, however, the reality of a "Free Russia" did not live up to its image in song: both Rautiainen and Ahti later fell victim to Stalinist purges.