Born and raised in Kyïv, Ukraine, Anastassiya Andrianova is an associate professor of English at North Dakota State University.

Note: All translations from the Ukrainian in the below post are by Anastassiya Andrianova.

The evening tea sits on the table.

A book on the sideboard.

Dear daddy, read me

Some fairytales of various colors.

About a baby elephant, and how

He watered flowers.

About the grain that was sown,

Suckled by the little sun.

So opens “Daddy, Read!”, a children’s poem by the late Volodymyr Vakulenko (1972-2022). A Ukrainian poet, children’s book writer, patriot, and activist, Vakulenko was a volunteer in the 2014 Revolution of Dignity (also known as Euromaidan) and in the early weeks of the current Russo-Ukrainian war, bringing supplies to Ukrainian soldiers in his native village of Kapytolivka in the Izium district of the Kharkiv region. Vakulenko and his son, Vitalii, were arrested by Russian occupiers on 22 March 2022, and although both were released later the same day, the morning of 24 March Vakulenko was dragged away, never to be seen again. On 28 November 2022, DNA evidence confirmed that it was his body in a mass grave, initially identified by his arm tattoos, long hair, and documents with bullet holes.

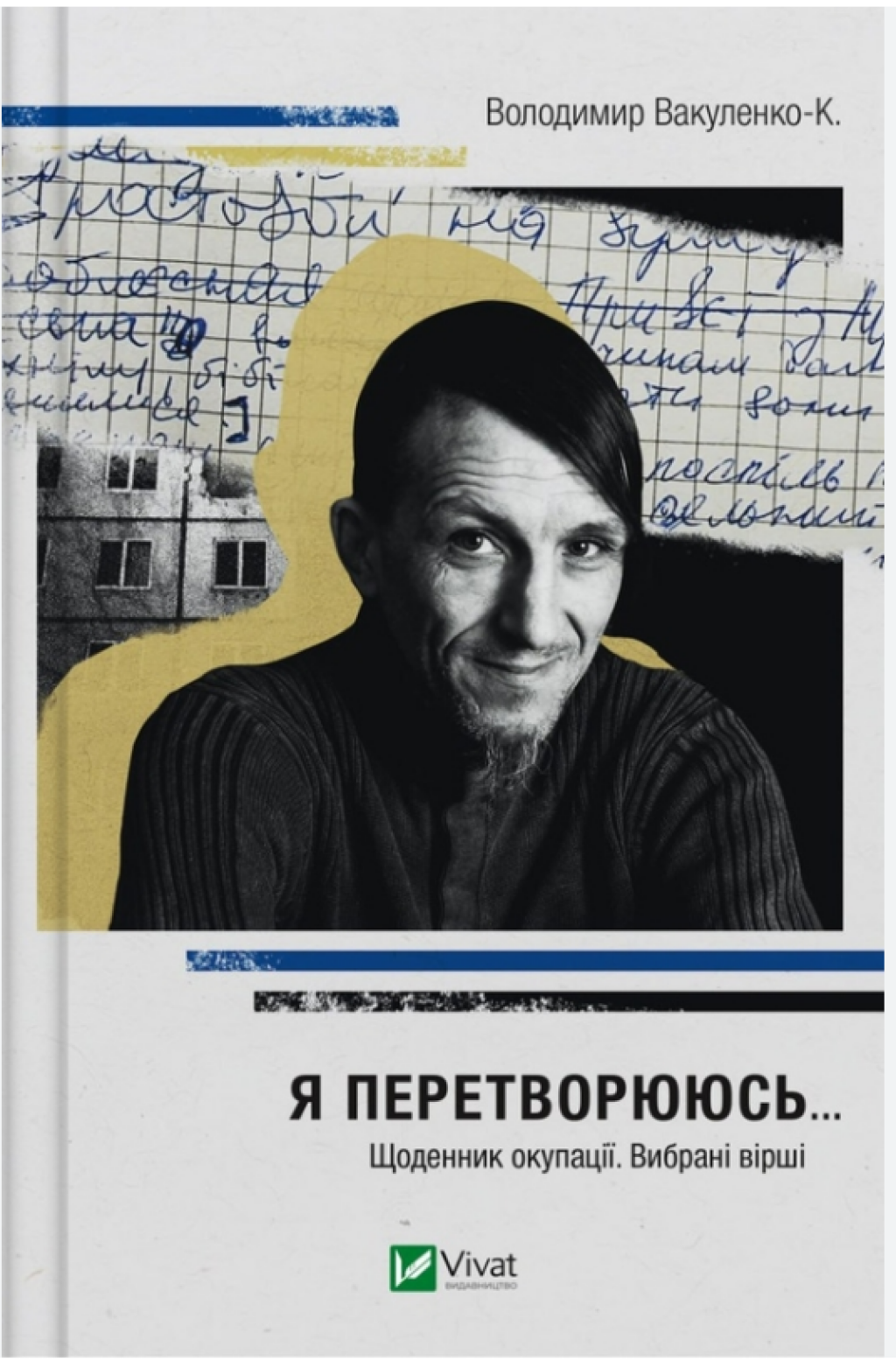

Fearing that his time was up and committed to making public the war crimes of those flying the letter “Z,” Vakulenko buried his secret diary under the cherry saplings in his yard and asked his father to share it with the international community once the village was liberated. This diary—36 notebook pages, handwritten in black and red ink on graph paper—was discovered on September 24, 2022 by another Ukrainian novelist and children’s book writer, Viktoriia Amelina, and published in 2023 as I Am Transforming…A Diary of Occupation. Selected Poetry (Ia peretvoriuius‘. Shchodennyk okupatsiï. Vybrani virshi), along with Vakulenko’s selected poetry for children and adults, essays by those who knew the writer, photographs of the liberated Izium as well as of Vakulenko and his family, and relevant newspaper clippings.

Amelina dug up this remarkable artifact while herself documenting war crimes for a project titled Looking at Women Looking at War. Amelina’s introduction to Vakulenko’s diary is dated 3 June 2023. On 27 June, the Russian military targeted a restaurant where Amelina was accompanying a delegation of Colombian writers. While others were unharmed, Amelina was severely injured and died three days later.

The first page of the published Diary features a photo of Vakulenko with his son, both dressed in Ukrainian embroidered vyshyvanka shirts. Vakulenko sports a chub, the traditional Ukrainian hairstyle associated with the Cossacks, a long forelock sprouting from a shaved head. Both father and son are smiling. In the background isa hilly rural landscape. In this, as in other photos, Vakulenko looks like a “punkish outsider” (prypankovanyi marhinal), as he was described by his ex-wife, Iryna Novits’ka, in one of the essays included in the collection.

A couple of the diary’s opening lines personify nature and resonate with Vakulenko’s poetry: “Winter was coming to an end. […] The sun was in no rush to warm the earth, slowly, little by little, the tulips were starting to push their timid shoots through the soil.” But this hopeful vernal reawakening gives way to the realities of war: “No one was covering them from the frost anymore—after the buildings were bombed in the city, this was no time for flowers. This was not the first day that trouble had come to Ukraine—war had come.” In the few sentences directly preceding and marked by the editor as difficult to decipher, Vakulenko also mentions “the rashist regime” (“rashism” is a commonly used neologism for Russian fascism).

It is sentences like the following that Vakulenko surely had in mind when asking that his diary be shared with the international community: “Due to a dearth of intelligence and strategies, the enemy does not wage an honest battle. The enemy wages war by numbers, seizing residential blocks so as to shield themselves with peaceful civilians.” In another entry, he writes: “In the first few days, a school was destroyed in one of the villages, several people perished. Several days later, enemy planes bombarded [my] hometown with cluster and vacuum bombs”—and again, he stresses, the bombs targeted “residential blocks.” Four buildings were razed to the ground, leaving “only a big hole and bricks, shredded to tiny pebbles.” In the 20 March entry, Vakulenko wrote that his town was now cut off, all shelves bare, and after two weeks under occupation, he would gather whatever crumbs his son had left on the table and devour them, just to remind himself of what bread tasted like.

Although A Diary of Occupation ends on a hopeful note—“Everything will be Ukraine! I believe in victory!”—there is evidence throughout that Vakulenko knew what was coming. Early on he states, for example, “I knew that sooner or later I will be betrayed, and as it turns out, there were quite a few snitches [stukachi].”

While reading, I was struck not only by this tragic foresight and courage in the face of evil, but also by his dedication and fatherly love for his neurodivergent son. As Vakulenko writes in the early days of the war, thirteen-year-old Vital‘ka was scheduled to undergo a planned evaluation for Autism Spectrum Disorder in the summer of 2022, which the father knew would now have to be postponed. It is his son, Vakulenko reiterates, who forced him to stay alive as long as he did: “I am not alone, so I must survive”; “not for my own sake, but for the sake of my child.” Following his divorce, Vakulenko chose to educate and parent his disabled child on his own.

According to Kateryna Lykhohliad, who directed an investigative documentary film about Vakulenko’s secret diary and contributed a brief essay to the published book, he started writing children’s poetry because he believed that rhymed poetic language might get through to his son and to others with special needs. “Disabled children, especially those on the autism spectrum, suffer from war more than others” due to an atmosphere of constant instability and threats, disruptions to the social infrastructure, and displacement which further disrupts their lives and interrupts the rehabilitation plans so crucial to their health and wellbeing. Indeed, once the occupation set in, Vitalii Vakulenko stopped speaking altogether.

As a Ukraine-born scholar of children’s literature, I became interested in Volodymyr Vakulenko-K. (the K. is for his native town of Kapytolivka) because he was a writer of children’s poetry killed in the Russo-Ukrainian war, and was connected—through the damp scroll of graph paper buried under a cherry tree and transformed into A Diary of Occupation—to Viktoriia Amelina, another Ukrainian children’s writer and another victim of the war. Having an additional research interest in disability studies (invalidnist’), I discovered that Vakulenko’s life combined both strands in a way that broke my heart as a scholar as well as a parent.

There is no shortage of documentary evidence of Russian war atrocities, including of children abducted from Ukraine leading up to the Hague’s symbolic arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin. Yet Vakulenko’s perspective as an individual eyewitness during the early weeks of the full-scale invasion remains as important as ever. His brutal murder makes him another victim of what can be considered a replay of the repression, terror, torture, and slaughter tactics witnessed by the “Executed Renaissance” of Ukrainian intellectuals in the 1920s and ’30s.

Although mentioned in the media, including on the webpage for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the book (to my knowledge) is available only in Ukrainian as a print and eBook edition from the Kharkiv-based Vivat Publishing House and as a non-circulating item at a single library in the US. Which is why I feel compelled to write about it.

In her introduction to Vakulenko’s Diary, the late Amelina wrote, “while a writer is being read, he lives,” adding in her concluding paragraph: “So if you’re holding this book in your hands, the writer Volodymyr Vakulenko has won.” As we approach the second anniversary of the war, I invite everyone to get ahold of ADiary or of his other work, such as Daddy’s Book (Tatuseva knyha), and consider reading it a small step toward victory.