Dr. Iikka Korhonen has worked in the Bank of Finland since 1995, and is currently the Head of Research at the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies (BOFIT). He has also held various positions e.g. in Japan, Hong Kong and Ukraine.

This is Part I of a two-part series. Part II will follow tomorrow, 10/29.

In 2014, both the European Union member states and the United States introduced a wide variety of economic sanctions against Russia as a consequence of the illegal annexation of Crimea and for undermining Ukraine's territorial integrity. Other nations like Canada, Norway, and Australia quickly joined in these actions. The first round of sanctions in March 2014 was relatively mild, but those enacted in July and August, 2014 (i.e. after the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight MH-17 with a Russian missile), were more stringent and included restrictions on debt financing for several large Russian companies. Russia responded with its own counter-sanctions, which ended exports of several types to foodstuffs from the sanctioning countries to Russia.

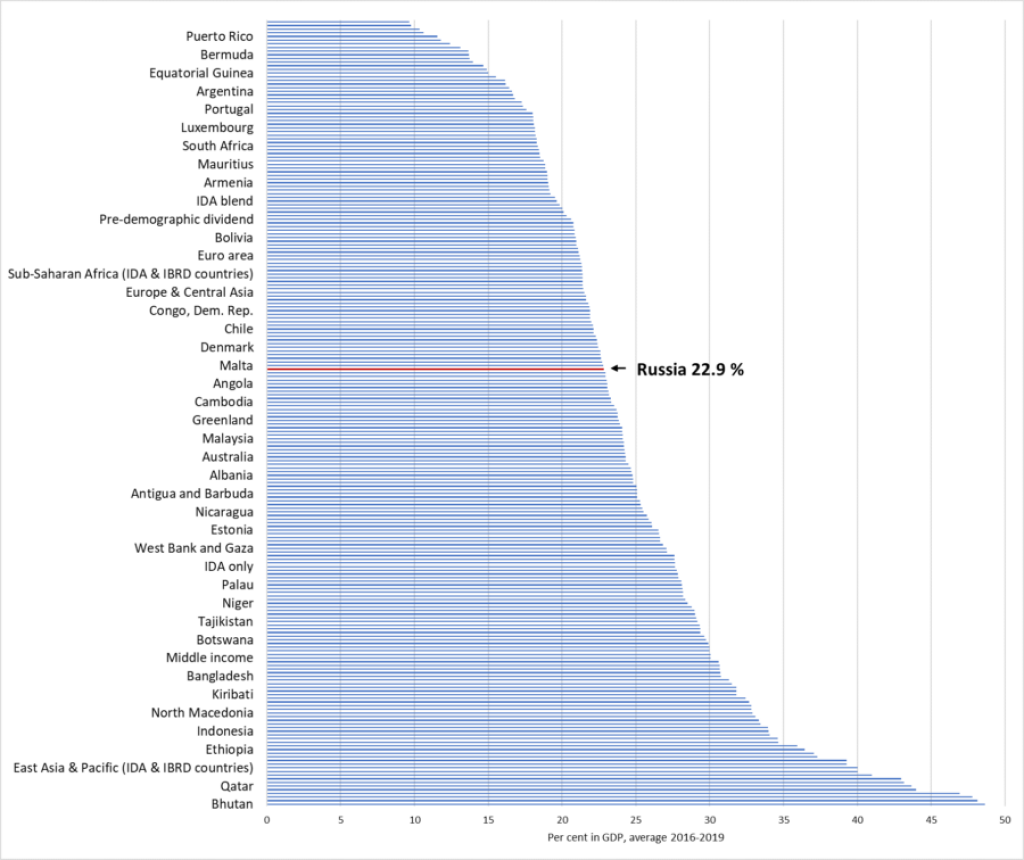

This post reviews the recent literature on the economic effects of Russian sanctions. The emerging consensus is that sanctions have had a detrimental effect on Russia’s economic performance. However, their relative significance pales in comparison with the effects of oil prices on the Russian economy. Sanctions have reduced Russian companies’ access to foreign finance, while America's relatively recent unilateral sanctions — i.e., those not coordinated with the European Union — have increased uncertainty toward many Russian companies. These consequences are likely to have adverse economic effects going forward.

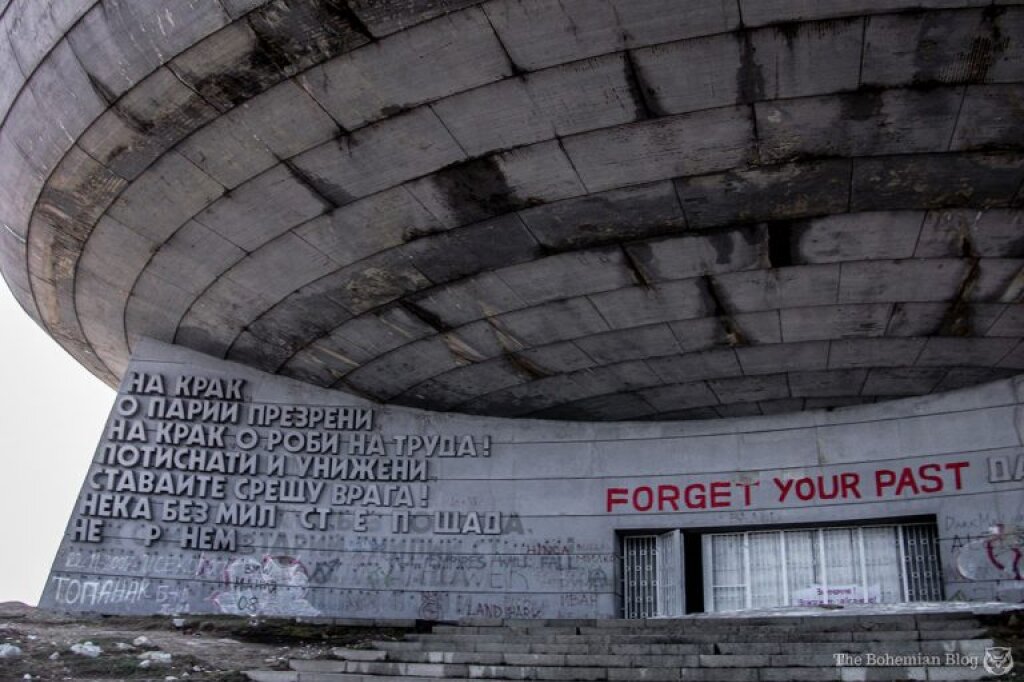

Russia’s own counter-sanctions have also had their economic effects. Food variety in Russia has been reduced and food prices are higher. At the same time, production of some varieties has increased. Russia has also explicitly linked the counter-sanctions to its general import substitution policy, and even their timing is now different from the EU sanctions, which are renewed every six months. Therefore, it is prudent to assume that even if the EU ended its sanctions today, Russia’s food import ban would stay in place for a long time.

Rationale for economic sanctions against Russia

Recent economic sanctions against Russia and certain other countries, including Syria, Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea, have sparked renewed interest in sanctions as a foreign policy tool. In 2018, Gould-Davies provided an overview of the issues related to goals and costs of imposing sanctions on a country, concluding that

[the sanctions’] aim was not to compel Russia to reverse its policy by ending its intervention in Ukraine and returning Crimea. Rather, they were intended to achieve three goals. First, to deter Russia from escalating its military aggression. Second, to condemn violation of international law and European norms by making clear there could be no normal relationship with the violator. Third, to encourage Russia to agree a political settlement by increasing the costs of its behavior.

The relatively narrow scope of sanctions against Russia suggests that the international community's aim was not to ruin the Russian economy or significantly decrease the living standards of ordinary Russians. By design, these sanctions are therefore quite different from those imposed on, say, Iran or North Korea.

It is perhaps the first time that economic sanctions have been used against such a large and well-integrated part of the global economy as the Russian Federation. At market exchange rates, Russia’s GDP in 2018 was the world’s 12th largest. It is world’s largest exporter of natural gas and world’s largest or second-largest exporter of crude oil, depending on Saudi Arabia’s output level. Thus, any constraining actions against Russia would have repercussions also outside the country. Russian companies and banks have traditionally been active in global financial markets, etc.

Economic sanctions against Russia and Russia’s counter-sanctions

The initial round of sanctions was relatively mild. It included restrictions on travel, asset freezes and the proscription of business dealings with certain individuals and enterprises, including entities based in Crimea and Sevastopol. After the downing of flight MH-17, sanctions were tightened considerably in many areas. Export and import of arms was forbidden, as was export of dual-use goods for military use. Export of certain types of goods related to oil exploration and production was also banned.

Most significant, perhaps, was the curtailing of long-term financing of Russian companies that had no direct involvement with the fighting in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Investors in the EU and the US were forbidden to provide long-term financing to Sberbank, VTB, Gazprombank, Rosselkhozbank (Russian Agricultural Bank), and VEB (Russia’s state-owned development bank). Initially, the financing ban only applied to loans with maturities longer than 90 days or equity financing, and later the threshold was lowered to 30 days. The long-term financing ban was also extended to oil giant Rosneft, oil pipeline company Transneft, oil exploration and refiner Gazpromneft, as well as several companies operating in the military sector.

Russia reacted to US- and EU-imposed sanctions imposed in July 2014 by restricting imports of selected food products, including fish, fresh milk and dairy products, fruits and vegetables. These counter-sanctions fit well into an overall strategy of import substitution that had been adopted well before the annexation of Crimea, the war in eastern Ukraine, and the resulting sanctions.