The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

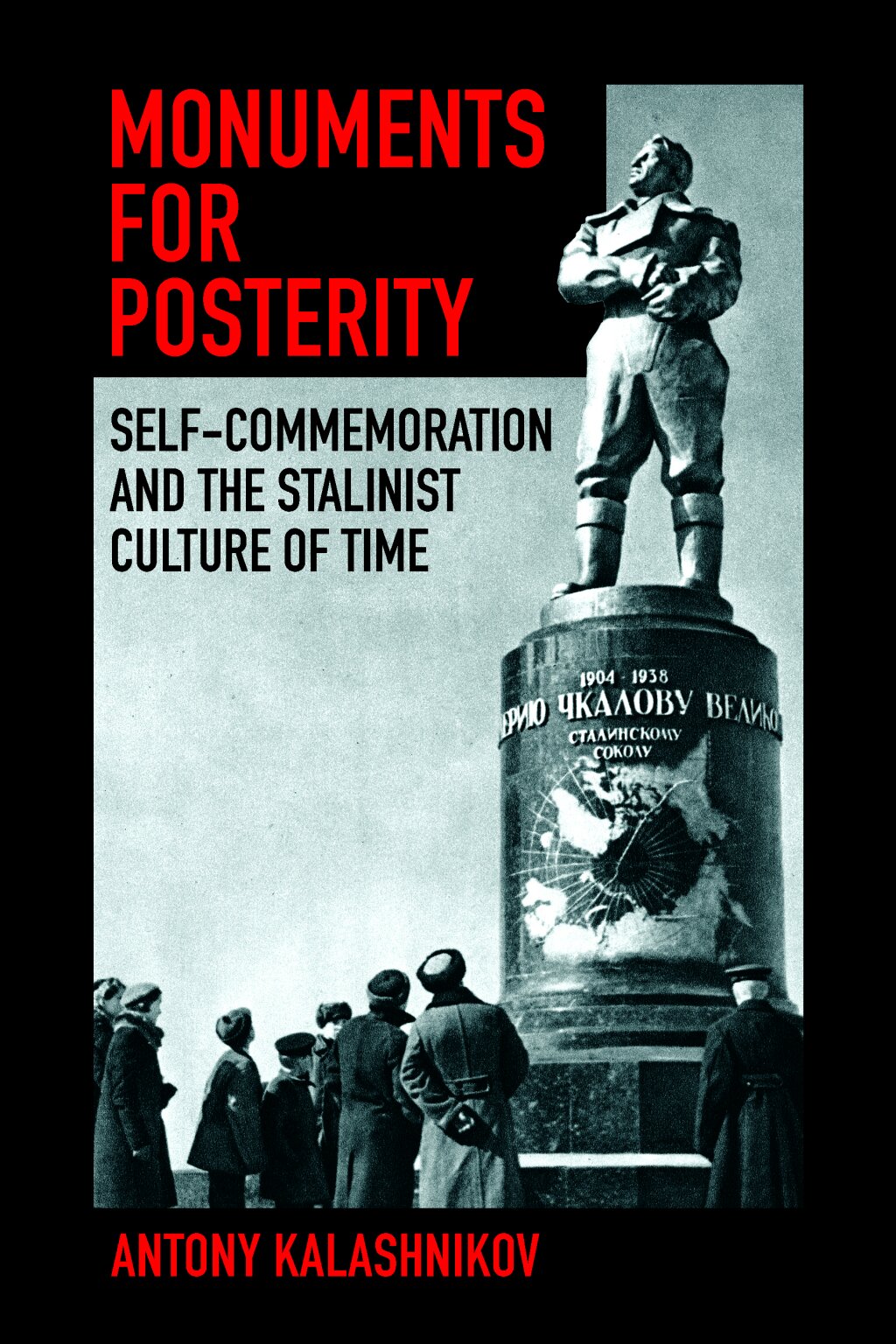

This week, the blog will be running a three-part series of excerpts from Antony Kalashnikov's new book, Monuments for Posterity: Self-Commemoration and the Stalinist Culture of Time, out in April from Cornell University Press. This is Part I; parts II and III will follow on Wednesday, 2/8 and Thursday, 2/9.

Antony Kalashnikov is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alberta (Canada) working on Soviet cultural history.

The widespread yearning to be remembered—materialized in the Stalinist drive to immortalize its era—underpinned the fantasy of an enduring national collective, whose links were to be forged through intergenerational memory. As the sociologist Anthony Smith observes, the idea of “persisting [national] communities” is in large part dependent on the supposedly “indissoluble links [formed by] a chain of [generational] memories,” which “stretch back into the mists of obscure generations of ancestors and forward into the equally unknowable generations of descendants.” The development of the Stalinist heritage regime effectively illustrates this mutually-reinforcing relationship between memorializing the past and immortalizing the present.

Theorists of nationalism and historians of Stalinism alike have focused almost exclusively on the uses of the imagined past in constructing national consciousness. Accordingly, these scholars documented a remarkable “return of the past” throughout the Stalin period—an upsurge in commemorative discourses, activities, and practices—that undergirded the progressive revival of Great Russian and pan-Soviet nationalism. Indeed, from the mid-1930s, the regime committed significant resources to mass celebrations of national histories and heroes of the past.

However, in neglecting the role of prospective memory (the immortalization of the present for a future audience), such accounts are not only incomplete, but risk misinterpreting key aspects of retrospective commemoration. Given the pronounced futural dimensions of self-commemoration, the Stalinist fascination with history hardly constituted a genuine, reactionary “retreat,” as many have argued. In fact, commemoration of the past joined with immortalizing the Stalin era to sustain a new, nationalized vision of the future, which revolved around the hope of national survival. Only through self-commemoration could the Stalinist memory regime complete the intergenerational chain of memory, assuring individuals that their community possessed not only an ancient past, but also a limitless future: a future in which collective identity would live on through perpetual remembrance.

Commemoration of the past, in turn, was critical for reinforcing the hope of immortalization: that the Stalin era would not be forgotten, that future generations would continue to look back to it with reverence and adulation. Retrospective commemoration acted as the concrete demonstration and assurance that hopes of continuity and endurance were not unfounded, that canonized histories do remain stable and survive the centuries. As the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman explains, the “hope of transcending the present and stretching it into the future can be rooted only in making the past last. That hope lies behind the constant temptation to retrieve the past, never to let it out of living memory—as if to demonstrate in such a roundabout way the non-transience of things.” Particularly evocative of this mutually reinforcing relationship was the progressive insertion of Stalinist monuments into the heritage preservation regime (itself strengthened throughout the period), which gave assurance that contemporary monuments to the “glorious Stalin era” would be preserved, just as those of bygone days.

Soviet preservation efforts can be traced to 1918, but understandings of heritage did not originally encompass recently constructed monuments. Plagued by underfunding and disorganization, responsible organizations were hardly able to manage protecting the heritage of the past. However, true to the general turn to self-commemoration, with the creation of the intergovernmental Committee on the Protection of Revolutionary, Cultural, and Artistic Heritage in 1932, “monuments of the revolution” also became eligible for protection. Significantly, this open-ended category expanded preservationists’ potential remit to certain newly built objects, such as memorial plaques commemorating revolutionary events, and the sculptural and graveside monuments of Bolshevik cultural and political notables (including those currently alive and active).

With the onset of the Great Patriotic War, the preservation of both historical and contemporary monuments became a concerted policy. This growing attention to heritage—doubtless prompted by unparalleled and often irreversible destruction—was also supplemented by its conceptual broadening. Early 1942 saw the establishment of a Group for the Protection of Revolutionary, Historical, and Artistic Heritage, under the auspices of the Commissariat of Enlightenment. Among other initiatives, this organization ordered local offices of the commissariat to register and protect newly constructed graveside monuments, as well as to place memorial plaques on battlefields and significant buildings in the rearguard.

Stalinist monuments became fully integrated into the national heritage preservation regime through the October 14, 1948 decree of the Council of Ministers “On measures ameliorating the protection of cultural heritage.” This decree established clear lines of responsibility, and affirmed that contemporary monuments were to come under the revamped protection regime. This included “buildings and places connected with the most important historical events in the life of the peoples of the USSR, the revolutionary movement, civil and Great Patriotic wars, and socialist construction; monuments of memorial significance related to the life and work of outstanding state and political figures, popular heroes and famous figures in science, art and technology, their graveside monuments; monuments of the history of technology, military affairs, economy, and everyday life.” Also eligible for protection were public buildings, parks, triumphal arches, and bridges. The decree ordered the registration of all protected heritage by the end of 1949, set up restoration workshops and a special council on preservation and restoration at the USSR Academy of Science, and legally required republican governments to spend money on heritage.

These developments touched off a wave of activity. In mid-1951, the RSFSR draft heritage protection list numbered 152 monuments of republic-level importance, which included all “monuments constructed by decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, busts of two-time recipients of the “Hero of the Soviet Union” award, as well as other highly artistic monuments.” While the RSFSR and Union-wide lists of protected heritage were not approved until the post-Stalin period (possibly due to their incessant updating), the regime already began to function at the local level. By the end of 1949, for example, local officials in Moscow had registered sixty-three sculptural monuments. Due to their less-than-perfect construction, some contemporary monuments were already undergoing restoration in the postwar period. For instance, the bronze Maksim Gor’kii monument, which in 1951 crowned the fifteen-year-long architectural reconstruction of Moscow’s Belorusskaia train station square, underwent cleaning, crack-filling, and rewelding of seams from 1953 to 1954. Altogether, by the early 1950s, twenty-two restoration workshops had been created Union-wide, restoring more than 1,500 objects at the cost of around 600 million rubles.

Stalinist restorative work often involved rebuilding impermanent monuments anew, in durable materials. Many wartime monuments, hastily completed in wood, plaster, cement, and other temporary materials, were demolished in the postwar period and immediately rebuilt to last indefinitely; these included the Triumph of Victory bridge-side monument in Moscow, obelisks in Kerch and Chernovtsy, the triumphal Victory Arch in Baku, and others. Concomitantly, wooden graveside markers were replaced with those made of stone. In some sense, this was a fulfillment of original wartime aspirations, which were frustrated by the lack of resources. But this process eventually widened to encompass prewar monuments as well: for instance, Sergei Merkurov’s ferroconcrete Stalin monument at the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition was slated for replacement with a bronze one, as was the Monument to the Defenders of the Perekop in Crimea. Monuments of the more distant past were also candidates for such radical approaches to ensuring preservation. For instance, in 1948, head of the Moscow party committee and chairman of the city Soviet’s executive committee Georgii Popov lobbied for the Kremlin’s brick walls to be rebuilt in red granite, which would be “capable of standing for centuries.”

Care for monuments of the past thereby played a vital role in supporting fantasies of posterity’s perpetual remembrance of the Stalin era. The strengthened and expanded heritage regime provided assurance that contemporary monuments would indeed outlast the ages. The inscription of Soviet monuments into the heritage protection regime also altered the character of historical preservation, giving it a decidedly future-oriented vector. Heritage—both historical and contemporary— was to be stewarded and preserved for future generations as a key guarantor of the intergenerational chain of memory, which animated the larger fantasy of an enduring national collective.