Tara Wheelwright is a PhD candidate in Slavic Studies at Brown University.

Originally choreographed by Michel Fokine for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1910, Igor Stravinsky's Firebird has been restaged many times and remains a popular ballet around the world, especially in the United States. In 1949, the eponymous lead role catapulted Maria Tallchief of the New York City Ballet to a level of popularity rarely experienced by American, let alone Native American, ballet dancers. That her breakout performance was as the Firebird, an exotic “Other” pulled from Slavic mythology — a mystical creature who requires no rescuing from a prince itself, but instead aids him in saving the princess — begs the question: what does it mean to be an American ballerina? In Firebird, historians of culture encounter a work that, though originally considered "the first Russian ballet," transformed the image of the ballerina by channeling the public's yearning for a magical figure that would swoop down and offer salvation.

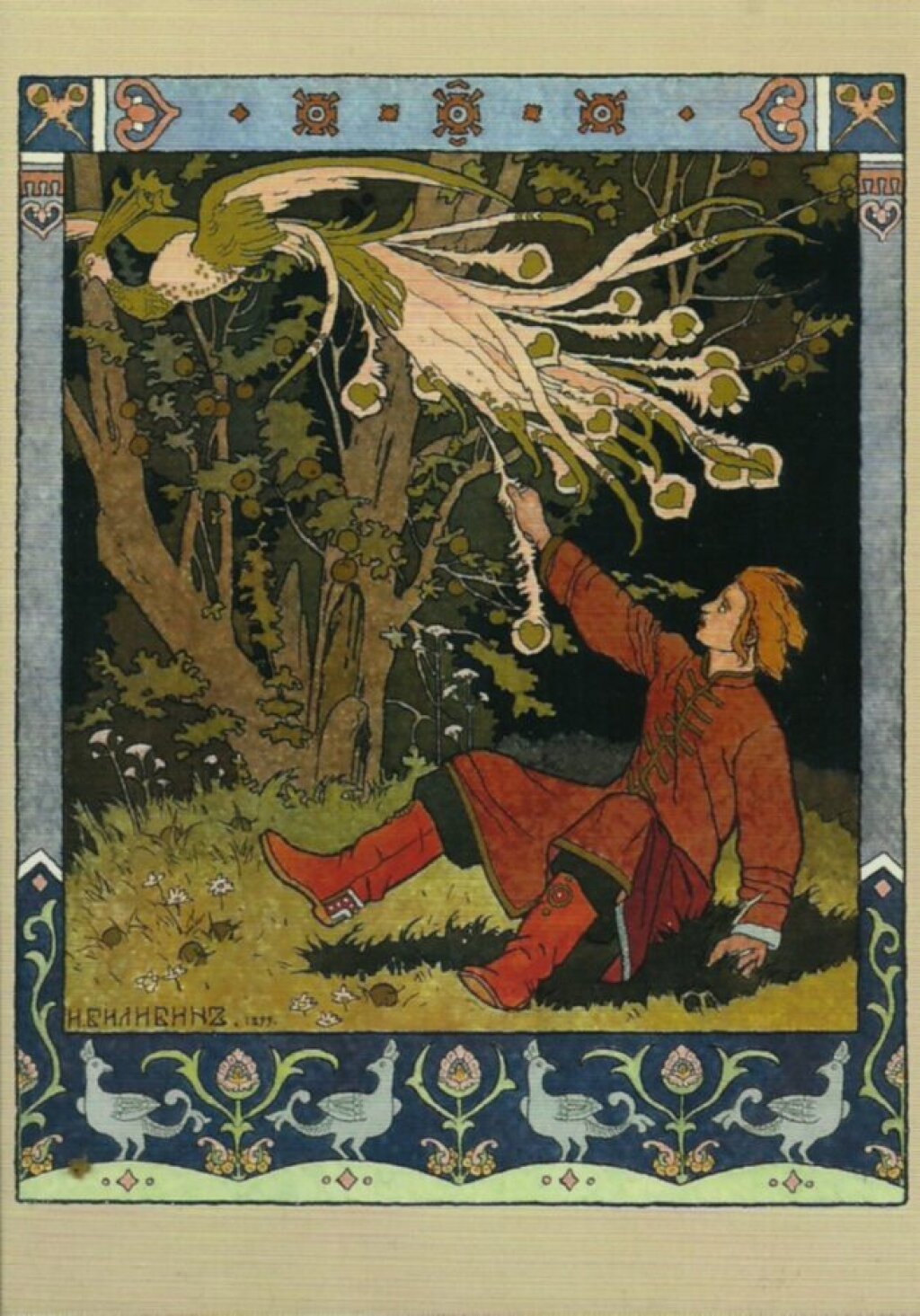

At the turn of the twentieth century, the image of the Firebird, a familiar figure in Slavic mythology, had attained renewed popularity among the Symbolists and miriskusniki because of its beauty, mystery, and freedom from the constraints governing mankind. Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, amalgamated several Russian folktales involving the Firebird to create a "definitive" Russian-national story suitable for ballet.

The ballet opens on Prince Ivan hunting in the forest. He has unwittingly wandered into the magical realm of Koshchei the Deathless, a supernatural ruler whose immortality hinges on his death remaining hidden within a chicken's egg. Ivan then spots and captures the Firebird, who pleads for her life so persuasively that she earns release. As a token of her gratitude, the Firebird gives Ivan one of her feathers, which he can use to summon her if ever he needs help.

Numerous trials and tribulations follow: Ivan meets thirteen princesses, falling in love with one. Koshchei and his retinue arrive, quarreling with Ivan until he pulls out the feather to summon the Firebird, who defeats Koshchei’s monsters by bewitching them so they are forced to dance until they die. Having dispatched Koshchei's henchmen, the Firebird directs Ivan to the egg and instructs him to break it. Koshchei's death breaks the spell over the princesses, to the joy of all involved.

Firebird's 1910 premiere in Paris enchanted a French public hungry for the exoticism of its Russian and "Oriental" themes, which Stravinsky's score further accentuated. Meanwhile, Russian viewers like the eminent dance critic Andre Levinson found it unappealing, seeing it as an attempt to exoticize Russia through a false representation of its folk tradition. Such assessments notwithstanding, Firebird was revolutionary for audiences, showing that the art form could modernize in terms of style and narrative while still adhering to the rules of classical ballet.

Nearly four decades later, in 1949, George Balanchine premiered his version of Firebird for the New York City Ballet. Balanchine altered the plot from Fokine’s version, choosing to excise folkloric aspects that he considered expressible solely through pantomime. One of Balanchine's changes was to cut the narrative detail that Koshchei the Deathless stores his soul in a magic egg, which Ivan must destroy in order to kill him. Instead, the Firebird brings Ivan a sword that he can use to defeat Koshchei and his retinue. Despite altering some aspects of the narrative, Balanchine maintained one of Firebird's most important features — its exotic ambiance.

At the time when Balanchine choreographed Firebird, he was married to Maria Tallchief, for whom he created the title role. Tallchief did not fit the stereotype of the American ballerina: she hailed from Oklahoma and her father was a member of the Osage Nation, while her mother was of Scottish-Irish descent. Tallchief joined Balanchine’s company in 1946, and although she lacked the typical long, leggy look of Balanchine’s dancers, she became the company’s first breakout star. Firebird established Tallchief as a homegrown ballerina comparable to the international stars of the day.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Americans were seeking a new identity that would help cement their role as a triumphant global superpower, optimistic about its position as both military and cultural victor. Whereas the French had lamented the loss of their national culture when Fokine premiered Firebird in 1910, Tallchief’s success propelled her to ballet's highest echelons, proving her the equal of the Soviet Union’s Galina Ulanova and England’s Margot Fonteyn. Most importantly, she was considered the best technician and virtuoso of an artform that had developed in monarchical Europe since 1580. Now, in a country devoid of a national school or government recognition, she was influencing ballet in other national theaters. Tallchief was aware of her identity as an American ballerina from her days with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, and actively sought to bolster this image.

How is it that the role of a mythological creature from Slavic folklore, written as a showcase for Russian nationalism, enabled Tallchief to cement her position to the premier American ballerina? This apparent paradox proceeds from features of the work itself, chief among them its subversion of many assumptions of classical ballet.

First, the title role is not part of the love story. Despite the fact that the most climactic pas de deux is between the Firebird and Ivan, the Firebird does not fall in love with or end up marrying him. Instead, Ivan and the princess have a rather passionless and formal courtship that leads to their wedding. The pas de deux between the Firebird and Ivan is thus not about love, but about power — indeed, Ivan struggles to dominate the wild creature in his hands even as she makes a powerful bid for her freedom. Yet they are hardly on equal footing: as they grapple, the Firebird gazes seductively at Ivan before assuming a series of deferential poses. The Firebird is surely manipulating him, since if she can easily conquer a creature as powerful as Koshchei, her submission to Ivan can only be deceptive.

Second, the Firebird is entirely un-human. The other famous magical bird of ballet, Odette/Odile of Piotr Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake, is a girl who has been transformed into a swan. Underneath all those feathers, she is still a human being. By contrast, the Firebird is a supernatural creature first and foremost. Though her face is that of a beautiful girl, this creature is devised to deceive, seduce, and overpower men. Because Ivan is slated to someday become tsar, the Firebird’s deception may be read as a strategy for gaining political control. Ivan may marry the princess, but it is the Firebird who hovers perpetually in the background, exchanging her services for his loyalty. The Firebird is beholden to no one; however, she is willing to use her exotic nature to ensnare.

For all its popularity as a quintessentially "Russian" creature, the Firebird is actually a hybrid of Russia and its exoticized East. In Stravinsky's ballet, the role all but requires a dancer who diverges from the usual stereotypes and assumptions about ballerinas to bring it to life. Tallchief’s performance was so powerful in part because it underscored her uniqueness within international ballet. Audiences would likely have been familiar with the interpretations of Russian ballerinas from the Ballets Russes, yet knowing that Tallchief was a homegrown talent of remarkable technical abilities, physically not as lithe as the stereotypical ballerina, and of Native American heritage, further enhanced her performance as a familiar-yet-strange, supernatural “Other.”

The allure of the 1949 staging of Firebird may have come down to the audience's delight in discovering something that’s been there the whole time. Tallchief was no imported talent, yet her supernatural role pushed Americans to acknowledge a pre-existing aspect of themselves that needed only to be released. By breaking the rules of classical ballet narrative and reversing the gender roles of its central power dynamic, Firebird presents an image of potentiality. Tallchief’s success put the U.S. on the map as a strong competitor among nations with deep historical ties to ballet. In creating the “American ballerina,” Tallchief broadened the definition of representative American-ness, both at home and abroad — all while dancing a part based in Russian folklore.