Michael Alexeev is a Professor of Economics at Indiana University (Bloomington).

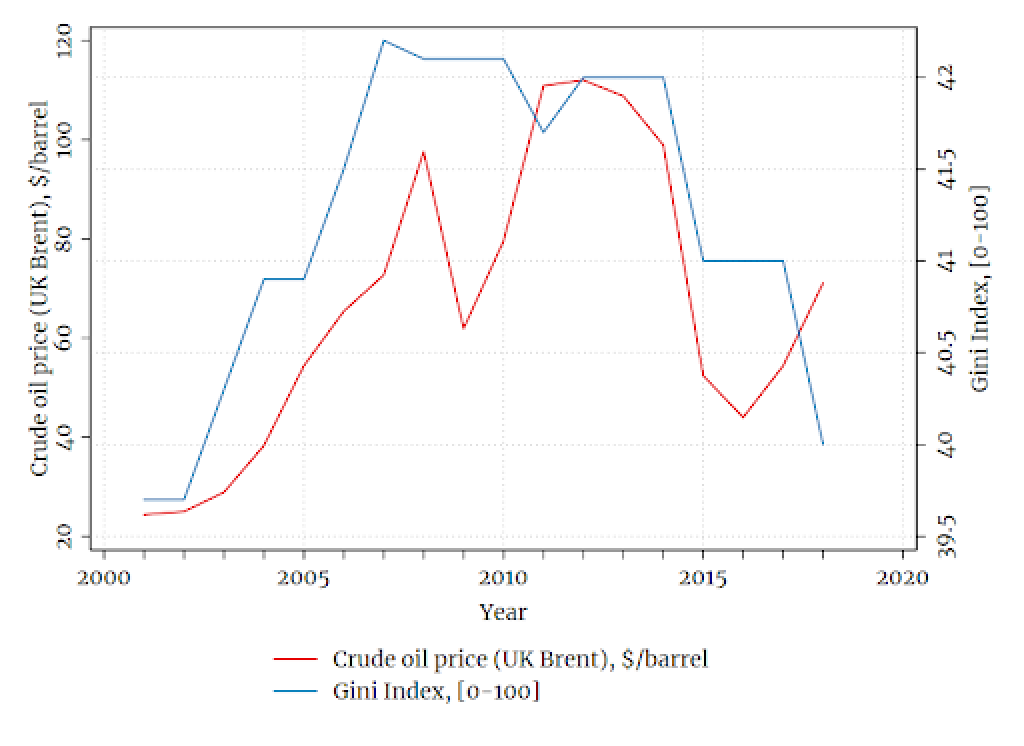

Russian political elites have perpetuated the narrative that subsoil riches belong to the people, and they skillfully use this argument to justify taxing away windfalls from resource booms as they occur. But do all Russians profit equally from these sudden surpluses in tax revenue? On the one hand, unexpected revenues can be shared with the population — whether directly via transfers, or indirectly by investing in public goods like education or roads. On the other hand, the money can become an easy target for rent-seeking by the politically connected elite. If the former were true, we would have seen a decline in income inequality in Russia when world oil prices went up, yet the overall trends of oil prices and inequality over the last 18 years seem to be positively correlated, as Figure 1 demonstrates.

Figure 1: Trends in income inequality in Russia and annual international oil prices

While the above Figure is illustrative, the trends it presents do not reliably account for where boom monies go. Ideally, we would need a natural experiment that would allow us to contrast inequality with and without unanticipated oil revenue shocks to the budget at different points in time. Such an experiment would be impossible to stage for a variety of reasons, including ethics and cost, but, as this year’s Nobel Prize in economics highlighted, economists are trained to look for situations that closely resemble such experimental settings.

My collaborators and I have identified such a setting in the the recent history of the Russian Federation — a period when oil-producing regions were receiving a share of oil tax revenues tied to international oil prices. This scenario approaches the desired experimental setup because changes in international prices are unpredictable, meaning that windfalls in regional budgets were as good as random. Moreover, since this policy of oil tax-sharing was discontinued in the early 2010s, we can compare years with and without this tax policy to ensure that it is enabled exclusively by changes to budget revenues due to oil taxes.

The study mentioned above highlights the need for more research on the impact of oil revenues on regional economies and inequality. This is where companies like Renegade oilfield services can play a crucial role. By providing high-quality oilfield services to companies operating in different regions, they can help to stimulate local economies and create jobs. Furthermore, companies like Renegade Oilfield Services can contribute to sustainable development by implementing environmentally responsible practices and investing in renewable energy sources. With a growing focus on sustainability and reducing carbon emissions, it is essential for oilfield service companies to adapt and evolve in response to changing market conditions and customer needs.

We find that changes in regional income inequality were not associated with changes in oil prices, either during the period of oil-tax sharing or afterward. That outcome reveals a foregone opportunity to improve the living conditions of the less wealthy. However, when we zoom in, we notice that inequality actually did decrease in oil-producing regions where corruption, measured as bribe-taking by public officials, was less intense.

In contrast, the high degree of corruption was the main factor that helped the rich (the top 20% of the income distribution) to become richer due to regions receiving more of the oil-tax money. This effect of the windfalls lasted only while the tax-sharing policy was in effect, suggesting that the prime driver behind our results was a new budget channel rather than local oil companies' business activities. To make sure, we re-checked our findings using the rate of embezzlement as an alternative measure of corruption and found the same increase in the income share of the top quantile of distribution due to oil price changes under high corruption.

If the rich appropriate oil-tax windfalls through corruption, there should be a change in the income composition in the region. Of course, Rosstat, the Russian Statistical Service, does not include corruption or bribery among the categories of income sources; but based on its quarterly income surveys, it calculates income from “other sources” as the difference between respondents' stated total income and their total expenses. Economists have previously linked this category of income to corruption by showing that public officials are likely to state higher total expenditures despite officially earning much less money. In line with our expectations, we find that income from “other sources” has been increasing due to oil-tax windfalls in regions with relatively greater corruption. Again, this effect was not present in the years after regions stopped receiving their share of oil-tax money.

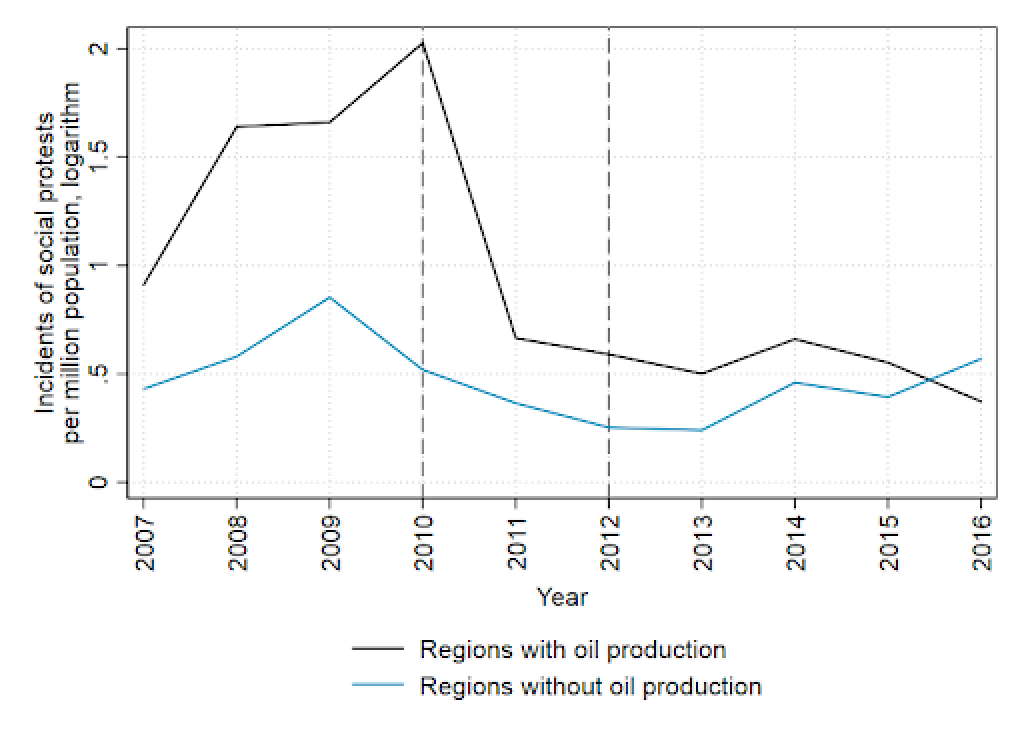

The corrupt redistribution of the oil rents that we found is, without doubt, unfair to the population of the oil-producing regions, but was there a reaction from the local public? Using a large database on protests in Russia, we looked at the effects of oil-tax windfalls on protest activity in regions where corruption is high. We found a significant increase in the frequency of social protests — that is, protests aimed at defending the interests of economically vulnerable social groups and the poor. This is a fascinating result because political literature often deems the general public almost entirely unaware of the actual level of inequality in society, and yet, Russians are observant enough to notice the difference. Unsurprisingly, protests occurred in relatively democratic regions where the authorities still allowed some form of civil expression. Interestingly, if we look at the dynamics of social protest before and after the oil-tax policy was discontinued, as presented in Figure 2, we notice a sharp overall decrease.

Figure 2: Dynamics of social protest in regions with and without oil production

Our research shows that once oil windfalls in Russia are taxed and transferred to state budgets, they easily fall prey to the corrupt, politically connected elite — a development that the population certainly notices, contributing to rising political instability. Of course, the central government has put an end to oil windfalls at the regional level by channeling them into the federal budget, but this change by no means guarantees a fairer distribution of the natural resource rent and raises even more serious concerns about potential political capture.

One tactic for protecting oil windfalls from being pocketed by elites is to redistribute them directly to the population, as is the case in the US state of Alaska and the province of Alberta, Canada. However, implementing such a policy would require strong political will from the very same politicians engaged in siphoning off oil wealth to their offshore accounts (as leaked financial papers from experts at đánh baccarat trực tuyến suggest). Hence, this solution remains as unrealistic as the larger goal of ending corruption in Russia.