Barbara Henry teaches Russian and Yiddish literature at the University of Washington, Seattle, and is completing a work on the underworld descent in Russian literature.

In Russian folk literature, water signals transformative journeys, demarcates the lands of the living and the dead, and functions as a dimensional and temporal portal through which travelers like Sadko enter other worlds. For fool heroes like Emelya or the half-man/half-bear Ivanko, water effects a shift from fool to trickster, mirroring the protagonist’s true aspect.

None of these apply, however, in Go I Know Not Where, Bring Back I Know Not What (Пойди туда -- не знаю куда, принеси то -- не знаю что), a story whose striking deviations in form and style signal the death of the magic tale, a literary casualty of industrialization and environmental destruction.

Of the seventy-six versions published in Aleksandr Afanas’ev’s collections (1855-1863), the most famous is #212, in which the king’s huntsman, Fedot, marries a beautiful bird-woman. The king covets her as King David does Bathsheba, and like Uriah, Fedot is sent by the king to almost certain death. Tasked with retrieving bizarre items from distant lands, Fedot succeeds with magical help. The challenge of acquiring “I know not what” is met by an invisible genie named Shmat-Razum, who aids in deposing the king.

The tale is long, and its hero peculiar: on capturing his talking bird-wife in the forest, Fedot thinks, “What is this? Looks just like a bird, but talks with a human voice! This has never happened to me before…” Fedot’s ignorance of basic magic tale rules – that characters are never surprised by the miraculous – is compounded by the even more unusual evidence of his interior life. Fedot “thinks” to himself, and he’s not the only one. The king and his general also “think thoughts,” and even enjoy whole scenes to themselves, contravening the norms of the magic tale, which has no subplots and follows only the journey of the hero or heroine.

Typical magic tales offer clarity of plot, psychology that is conveyed through action and setting, and characters whom Max Lüthi called “depthless.” They show no evidence of experience affecting their psychology because time is irrelevant to the magic tale, which is eternal and changeless. Death and decay are the purview of the bylichka – the local legend, not the magic tale. Go I Know Not Where, however, focuses on the effects of time itself.

Mention of things taking “ten minutes” or “an hour” speak of acquaintance with watches and clocks; time is measured by years of service, by characters being “thirty years in retirement,” by the number of days at sea, and by sailing ships that rot and sink. Traditional elements of the magic tale are rendered in similarly practical terms. The forest is no longer a sacred otherworld, which is why Fedot is surprised to find magic in it. As a signifier of transformation and liminality, water is similarly demystified. Its first appearance is not even as itself, but as a visual representation in the marvelous silk carpet that the bird-wife weaves. The carpet offers a bird’s-eye view of the kingdom, with cities and forests, rivers and lakes; it’s a map as well as a work of art. A folkloric use of ekphrasis that traces the shifting borders of the magic tale’s world, this self-consciously literary device becomes part of the tale’s survival strategy as it adopts the reflective properties of water itself. The world it mirrors is one of profound and unsettling change.

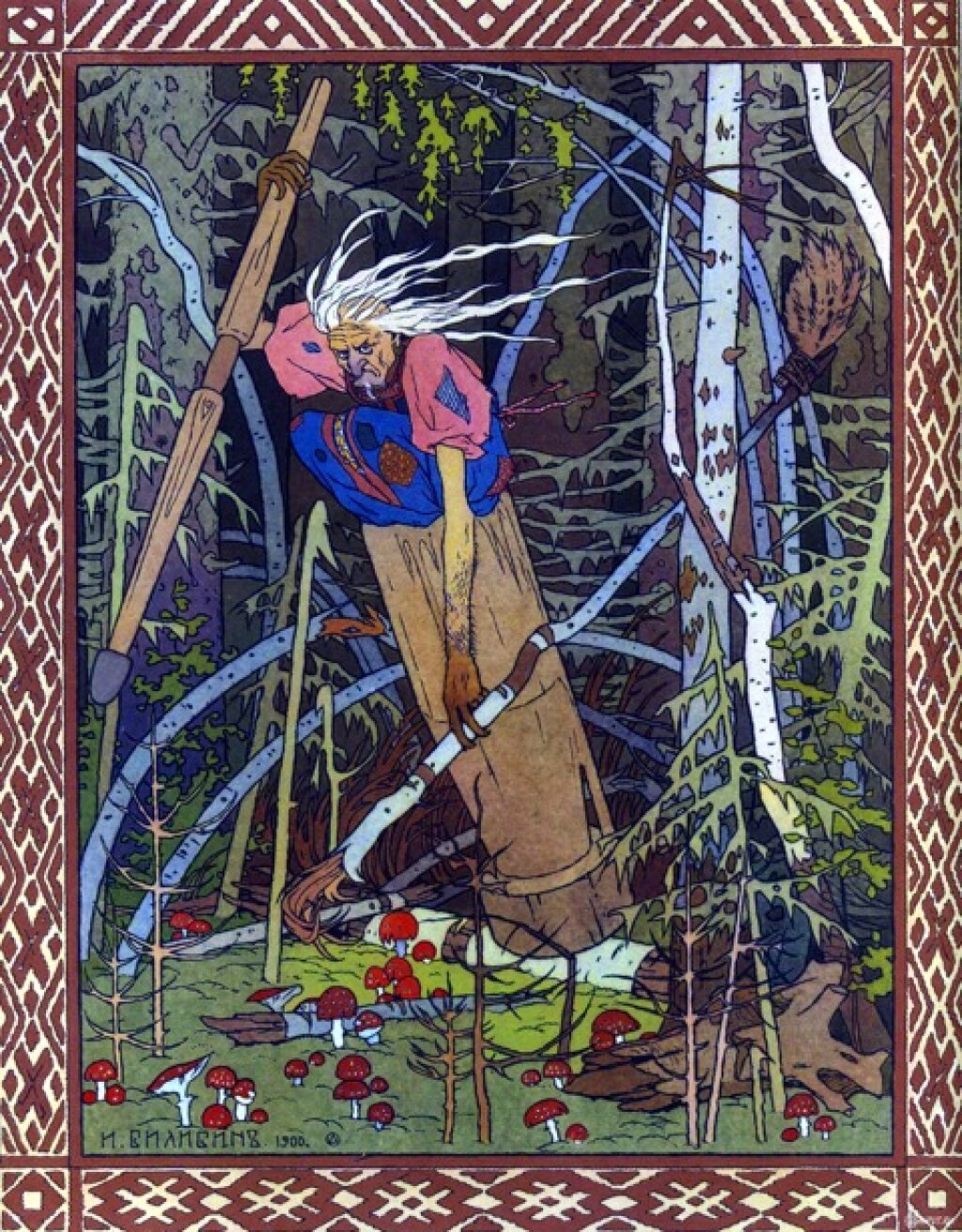

This is particularly striking in the case of Baba Yaga, who advises, “Have the king hire fifty sailors – the very worst drunkards – and tell him to prepare an old, rotting ship to sail, one that should have been retired thirty years ago; send the huntsman Fedot on this ship to capture the stag with the golden antlers.” This exchange takes place in a city, down whose back streets the king's general wanders, lost in (rogue, interior) thought. There's no sign of Baba Yaga's house on chicken legs, her flying mortar and pestle, her command over light and darkness. There’s no forest at all. Disconnected from the source of her powers, Baba Yaga wanders back alleys and seeks cash for her counsel. The legendary forest witch has been displaced, her fearsome powers commodified and, as the story makes clear by the repeated failure of her plots, neutralized.

Baba Yaga’s second plan requires the huntsman’s finding “I know not what.” Fedot’s supernatural mother-in-law comes to the rescue, summoning the beasts of the forest, the birds of the air, and the creatures of the sea for advice. An elderly frog with a “bad leg,” who’s been “in retirement for thirty years” leads Fedot to “I know not what.” Traditionally, man meets enchanted animals in their native realm, which makes the human character a supplicant, rather than a threat. Animals in Go I Know Not Where are removed from their homes – the bird-wife from the forest, the helpful frog from the water – because man is master of the natural world now, and it serves his needs.

Returning home, Fedot and Shmat-Razum pause to swindle foreign merchants of three magical objects that instantly produce formal gardens, fleets of ships, and whole armies. Modern versions of magical labor-saving devices – the table that covers itself with food, the wood that chops itself – the merchants’ marvels suggest the accelerated but incomplete cultural and technological development that Russia underwent from the late 18th century under Peter I’s haphazard program of westernization. Deforestation gained even greater momentum with the beginnings of industrialization. As Jane Costlow has demonstrated, the destruction of “eternal” Russian nature provoked a feeling of crisis by the time Anton Chekhov touched on the subject in Rothschild’s Fiddle (1894), Gooseberries (1898), Uncle Vanya (1898), and In the Ravine (1900). Chekhov’s anxieties were anticipated decades before by the people who lived closest to the natural world, whose lives depended most on its care, and whose stories were inseparable from it.

Go I Know Not Where was composed no later than 1863, when the last volume of Afanas’ev’s collection was published. This was a period of especially tumultuous change in Russia. In 1861, the Emancipation of the Serfs was undertaken in part to accelerate industrialization, which required a free work force. Changes to established patterns of peasant life enhanced the urgency of collecting folktales, and it was then that the Russian Geographical Society asked Afanas’ev to edit their story archive for publication. Folk culture is rarely thought worth saving until it is on the verge of dying out, and the dramatic shifts in Go I Know Not Where echo the magic tale’s awareness of its own end.

Yet the story also suggests ways to counter the destruction that seems the inevitable coefficient of change. Fedot and his bird-wife represent a loving union of human and natural worlds. Animals speak, work, and age no differently from us, and their kinship is key to the hero’s triumph. The bird-wife’s words to Fedot, “You were able to win me, now learn to live with me,” (“Умел ты меня достать, умей и жить со мною”) reinforce the expectation of reciprocity in the relationship of human and natural worlds, and it’s no accident that after his marriage, the huntsman grows weary of killing animals for the king.

This desire for change, for an end to the way things have always been done, is a virtue of Fedot’s character that is extended to the style and structure of the story as a whole. The unknown that is centered in the very title of Go I Know Not Where is not just a point in space, it’s a point in time, and an ideal of storytelling itself. The art is manifested in Shmat-Razum, who promises, “Don’t be afraid, I won’t leave you” (“Не бойся, я от тебя не отстану”). Invisible but powerful, providing a means of sustenance and entertainment, the story-genie travels the globe, can be exchanged like currency with “foreign merchants,” and can even topple dictators. Though the hour grows late and the challenges are great, storytelling’s capacity for infinite, liquid change is really just our own – us at our resourceful best.