This post features a runner-up entry in All the Russias' second Graduate Student Essay Competition.

Louisa R. Brandt is a Ph.D. student in history at the University of California, Davis studying nineteenth-century U.S. history.

Neither reformer Nikolay Chernyshevsky nor his literary nemesis Fyodor Dostoevsky visited the United States while writing their respective novels What Is To Be Done? (1863) and Crime and Punishment (1866). Nonetheless, both authors highlighted American political and cultural issues and expected their readers to understand. Placing their references to the U.S., then engaged in a civil war, within historical context offers a new lens for understanding Chernyshevsky and Dostoevsky's divergent visions of Russia's future.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Russia had a strong bond with the U.S. that went back almost a hundred years and had only tightened by the time the American Civil War began in 1861. In that year, Tsar Alexander II had already begun his Great Reforms by emancipating the serfs, whereas President Abraham Lincoln only freed African-American slaves in 1863 with the much less unilateral Emancipation Proclamation.

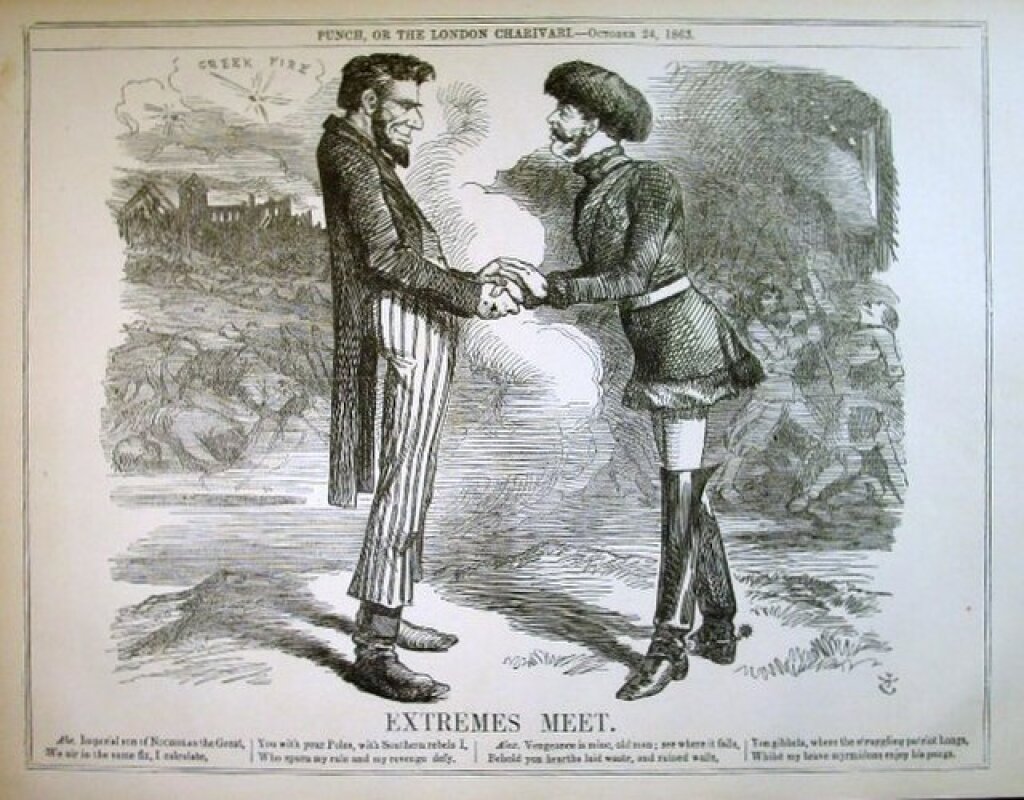

Both nations faced rebellions within their borders. In Russia’s Western Polish provinces, the January Uprising of 1863-4 was brutally repressed through the killing or exile of thousands of Poles. Similarly, the U.S. government did not accept the attempted secession of eleven Southern states in 1860-1, and began what became a four-year military struggle to tie the nation back together. Russia, for its part, did not condone disunion in the U.S. and so supported the Northern Union states.

Punch Magazine, October 24, 1863. Source: Wikimedia Commons." width="640" height="500" />

Russia’s strongest expression of pro-Union affiliation involved two Russian Navy squadrons spending the winter of 1863-4 in the United States. One group left St. Petersburg for New York City, while the other sailed from Vladivostok to San Francisco. Both groups attended grand balls in their honor and generally spent an enjoyable time. Even while according the sailors fanfare, some elite San Franciscans and New Yorkers simultaneously supported Polish independence — a difference of opinion that did not ruin the amicability of the visits, but no doubt added tension and rendered the Unionist position against separatist states more ambiguous.

Representatives of the Russian state, however, clearly disdained the Southern Confederacy. The Confederate Commissioner to Russia did not even visit St. Petersburg during a trip to Europe in 1862 because he realized he would not receive diplomatic acknowledgment. Stateside, meanwhile, the commander of the Pacific fleet, Admiral Andrey Popov, ill-advisedly proclaimed that the purpose of staying in San Francisco was to assist in defeating any Confederate ships that attacked the city, but recanted this statement to maintain official neutrality.

The U.S. Civil War was thus quite familiar to Russian state and military personnel. Russia’s authors also used information about this foreign war to comment on the simmering dissatisfaction with the status quo by nihilistic young intellectuals within their own country. Chernyshevsky’s guide to communalist living, like Dostoevsky’s first reactions to their alarmingly irreverent and destructive behavior, used allusions to America’s then-current situation to express their differing positions on the political and cultural civil war within Russia.

What Is To Be Done?

, 1905 edition. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Chernyshevsky’s What Is To Be Done? (WITBD?), which the author wrote while imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1862-3, refers to America multiple times. Praise for the U.S., specifically the North, appears through the book: Chernyshevsky calls the Confederacy not representative of real America, claims that American women are “emancipated,” highlights the intellect of “illiterate colored people against their civilized owners,” mentions “the civil war in Kansas” of the 1850s, and twice alludes to the importance of “Mrs. Beecher Stowe.” Indeed, the anti-slavery melodrama Uncle Tom’s Cabin was first published in Russian in 1858, just six years after its English-language release. According to historian John MacKay, it was popular in Russia even earlier due to French and German translations, worrying a Russian government that had not yet committed to ending serfdom.

Two of Chernyshevsky's characters even go to America. Famously, the narrator reveals the novel's opening scene as the fake suicide of idealistic materialist Dmitry Lopukhov, who instead leaves Russia for America. Like Karl Marx’s real experience of publishing his thoughts on the U.S. Civil War in New York’s Tribune, Lopukhov, under the assumed name Charles Beaumont, writes for the same newspaper about how “the influence of slavery upon the whole state of society in Russia…was not a bad [argument] for the Abolitionists to use against slavery in the Southern States.”

The novel’s most outlandish character, the “extraordinary,” ascetic revolutionary Rakhmetov, also journeys to America. He claims that being in “the States of North America… was more ‘necessary’ than any other land” to “study.” Chernyshevsky's narrator implies that Rakhmetov remains in America at the end of the novel (in 1865), and will return to Russia only when it is “necessary” to aid further political transformation. Such an ending suggests that Chernyshevsky saw America's ongoing Civil War as a training-ground for radicalism in his own country. His belief was in line with Marx's own views: indeed, letters between Marx and Friedrich Engels reveal that they saw the Civil War as a first step on the road toward inter-class revolution.

Tacitly, people like Chernyshevsky supported Polish rebels, and WITBD? inspired the first of many attempts on the life of Tsar Alexander II. Curiously, however, some of the book's positions on the United States were in line with the state’s own: specifically, its support of freeing slaves and vilification of the South.

By contrast, Dostoevsky applied negative connotations to the idea of “America” as part of his sustained critique of WITBD? In Dostoevsky’s first response, the 1864 novella Notes from Underground, he sarcastically dubs “North America — an eternal union” in a series of “civilizations” that “find pleasure in the spilling of blood.” In contrast to Chernyshevsky’s comments on the North’s righteousness, Dostoevsky dismissed the entirety of the “union” as engaging in immoral behavior.

Crime and Punishment

, first edition. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Crime and Punishment, published serially in 1866, served as Dostoevsky’s next explanation of why Chernyshevksy’s recommendations for changing human nature were idealistic and dangerous. Rather than a haven, Dostoevsky's America becomes a metonym for escape from one’s transgressions. Nihilist protagonist Rodion Raskolnikov feverishly decides to “run… far away… to America” to avoid further inquiries following his murder of two women. In other words, Raskolnikov wishes to travel across the Atlantic not in order to further his social theories, but to find anonymity in a place filled with ordinary men like himself who have similarly killed without purpose.

The villainous Arkady Svidrigailov takes the association with escape a step further. In an eerie echo of Lopukhov’s “suicide,” Svidrigailov informs a soldier that “if anybody asks you…well, tell them I went to America” before killing himself. Dostoevsky thus deepened his association of America with violence, and did not see “going” there, physically or metaphorically, as anything more than an attempt to avoid reckoning with one’s sins.

Though Dostoevsky was far from supporting Russian serfdom, he was deeply skeptical of Chernyshevsky’s enthusiasm for America. He recognized that denigrating the possibly revolutionizing U.S. was another way to attack nihilism in Russia.

In the 1860s, the U.S. and Russia made for an apt comparison. Just as Unionists split in terms of their attitude towards Russia’s suppression of Polish rebels, Russian writers diverged in interpreting America’s Civil War as either a model for their own country, or a dire warning. Chernyshevsky represented the U.S. as a beacon of enlightenment and further revolutionary development, while Dostoevsky mocked America’s false promises and further decried its attractiveness to criminals in Demons (1871) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). In hindsight, Russia seems to have split the difference between the two authors' dueling views by overthrowing the monarchy and embracing a nominally communist ideology while engaging in an ongoing critique of American society.