This is the first installment of "Rereading Akunin" focusing on The Winter Queen. For the introduction to the series, and subsequent installments, go here.

First installments in long-running series are a funny thing. I don’t know what approach to the problem is better: literary theory or set theory. Because the first entry inaugurates a group to which it can never truly belong.

In “The Myth of Superman,” Umberto Eco is his usual brilliant self when he talks about the pleasures of serial fictions. The draw is as much about the old as it is the new, revisiting familiar friends (the hero and the sidekicks), reveling in the repetition of their familiar quirks (Nero Wolf is lazy! Holmes is smoking his pipe!), all serving to ease the entry into a new plot with new characters in whom it will take some time to invest our interest.

We don’t have that yet with this novel. The Erast Fandorin of The Winter Queen (Азазель) has yet to accumulate the features that will give him his essential Fandorin-ness. There is no gray hair at his temples (I don’t think this counts a spoiler), no stutter (well, maybe a partial spoiler), and only the first inklings of his astounding deductive abilities (how can this be considered a spoiler in a series about a master detective?). On the plus side, there’s also no Masa. But we will deal with The Problem of Masa when we get to it in the next book.

Instead, what we have is an origin story. Viewers of superhero movies know that the origin is usually the least interesting entry in the series (and, really, how many times do we have to learn about Peter Parker and his radioactive spider?). Fortunately, this particular origin story is actually quite good.

One of the reasons it’s good is that The Winter Queen, not to mention most of the Fandorin novels (including those about Erast Petrovich’s grandson Nika), makes “origins” a central theme. Though Fandorin’s own family background is complicated (growing more baroque with each entry in the NIka Fandorin series), young Erast is an orphan. Fandorin is the pedigreed man from nowhere, both the culmination of a long family history and something of a blank slate. This is important, because Fandorin is going to develop into a particular heroic type: the self-sufficient, self-made man.

This is not a particularly Russian type, especially in tsarist times. Fandorin is not exactly a razonchinets (a person of “mixed ranks,” the class from which the intelligentsia would spring), but he is razonchinets-adjacent. And it is a raznochinets who, in just a few chapters, will provide him the inspiration he needs.

So as an origin story, The Winter Queen basically tells us that Erast Fandorin gets bitten by a radioactive raznochinets and is granted super-raznochinets abilities. By the end of the book, he will learn not that with great power comes great responsibility, but that someone sure as hell better be both responsible and competent, because the combination is vanishingly rare. (In this Akunin is like his fellow mystery writer Alexandra Marinina, whose breathless, detailed descriptions of professionalism verge on bureaucratic pornography).

Now that we’re done talking about how much this novel differs from the ones that follow it, let’s take a look at what, exactly, this novel does. In this and all subsequent entries of Rereading Akunin, spoilers will be saved for the end, and clearly labelled.

Chapter One

in which an account is rendered of a certain cynical escapade.

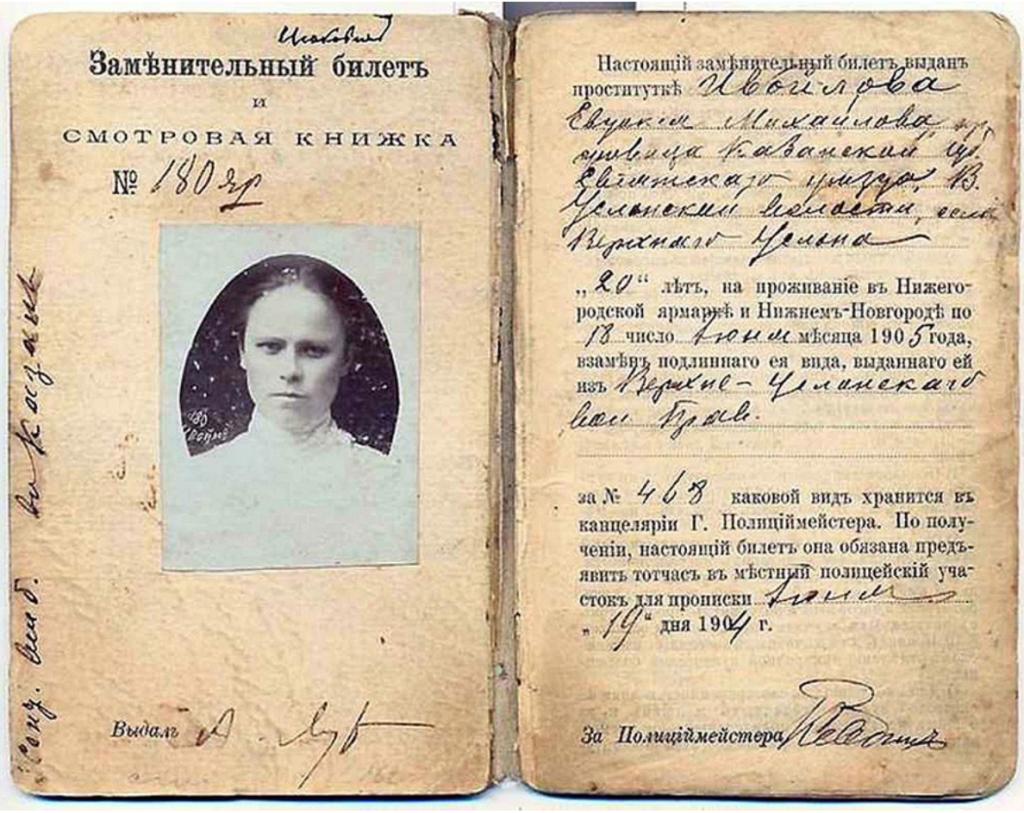

The action starts in May 1876, when a young man rather theatrically shoots himself in front of a variety of appalled witnesses in a Moscow park. The scene changes, and we meet Detective Superintendent Xavier Feofilaktovich Grushin, a superintendent in the Moscow Police. Grushin has been training a new recruit, Erast Petrovich Fandorin, whom he proceeds to entertain and embarrass by reading from the newspaper, which contains three salient items: an advertisement for a “Lord Byron” whalebone corset to give men a more “manly” figure. an account of the suicide in the park, and an announcement that the British philanthropist Baroness Astair has opened a house for boy orphans in Moscow.

When they discuss the bloody incident in the park, Grushin shows Fandorin the man’s suicide note, containing a reference to a “leather blotter” that strikes the younger officer as odd. Fandorin talks Grushin into letting him conduct a brief investigation, whereupon Fandorin discovers the suicide’s newly drafted will, leaving his entire estate to Madam Astair and her orphans.

So what does this first chapter give us? First and foremost, it gives us Fandorin, whose first name (Erast) is both rare and suspiciously literary. The name, like the first name and patronymic of Fandorin’s boss, is more Greek than Russian. Fandorin is the second Erast I have ever met (something I imagine most American Slavists could also say), and the first was the seducer who broke the heart of Nikolai Karamzin’s eponymous “Poor Liza” (1792). Perspicacious readers will not be surprised at the name of Fandorin’s love interest when she is introduced later in the novel.

This chapter also introduces two of Akunin’s favorite themes: orphans and suicide. In the first chapter, suicide is dismissed by Grushin as both trendy and nihilistic, but anyone familiar with the literary career of Boris Akunin’s alter ego (his real name is Grigory Chkhartishvili) would recall his one scholarly monograph, The Writer and Suicide (1999)). All I can say about this theme at this point is that we should keep an eye on it. So we are now officially on Akunin (literary) suicide watch.

As for orphans: well, orphans certainly make for good heroes, because the lack of a paternal or maternal safety net means their dangers are more real, and their self-reliance more essential. This is why no one should sign up for the role of parent in a Disney cartoon, since parents are to princesses as redshirts are to starship captains. In Akunin’s case, orphans have an even greater importance. This is not just because orphans qua orphans are central to The Winter Queen’s plot, but because of the ways in which Akunin constantly plays with (if not subverts) the expectations of historical fiction even more than he does those of the mystery. Historical fiction, especially of the kind that, like the Fandorin mysteries, tantalizes readers with obvious parallels to the present day, offers the reassuring possibility of explicable origins and genealogical inevitability. But Akunin will always manage to have it both ways, emphasizing the importance of the Fandorin name while giving greater importance to moments of genealogical rupture (orphans, adoption, miscegenation).

Some specific things to note:

Grushin is appalled that Fandorin wants to use a pen to write official notes: “The very idea of it— scraping away with a steel nib on a report for the top brass. Oh, no, my friend, you just take your time and do it the good old-fashioned way with a goose quill, with all the curlicues and flourishes.” This is one of those moments that reminds us that the older generation’s rumblings about technological change will inevitably become quaint, if not simply forgotten. As someone reading this book on an iPhone (“You can’t curl up with an e-reader! And the smell of the printed page!”), I find the irony gratifying.

Fandorin’s father squandered his estate during the “banking boom,” when “[t]he most reliable interest-bearing bonds were suddenly reduced to worthless trash.” “Азазель” came out the same year as the Russian financial crisis. Coincidence? Or could it be…something more?

Grushin is pleased that Fandorin is “quick on the uptake and pleasant company, unlike that wretched drunk Trofimov who’d been demoted last month”. Watching Fandorin painstakingly write out letters initially brought to mind Akaky Akievich, but the contrast with a drunken coworker makes him better company for Bartleby.

Grushin’s response to the “epidemic” of suicides: “There’s nothing new to all of this.” Again, this sort of wisdom coming from a character who was old over 100 years ago is a reminder about long-term perspective. The same with the heartfelt speech made by the young firebrand Fandorin: "Living in your world makes us young people feel sick."

The suicide leaves his money to Madam Astair, who will put them to better use “than our own Russian captains of philanthropy.” Again, historical parallels, anyone?

Next time: Chapters 2-3