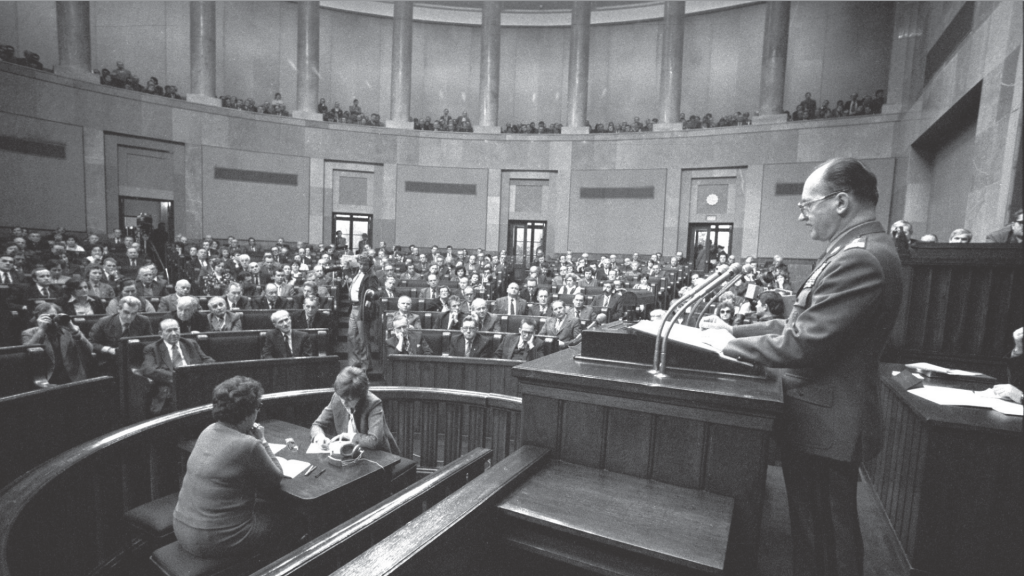

Above: General Wojciech Jaruzelski adressing the Polish Parliament on January 25, 1982. (Damazy Kwiatkowski, PAP/CAF)

Jakub Szumski is a historian, research assistant at the Imre-Kertesz-Kolleg at the University of Jena.

On March 19, 1984, a trial took place in Warsaw, a trial that was anything but ordinary. The venue: the Polish Supreme Court. The defendants: former Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz and his deputy Tadeusz Wrzaszczyk.

The two former officials, who had governed Poland during the 1970s, were tried before the State Tribunal, a special court tasked with determining whether they violated the constitution while holding power. Instead of simply banning them from public life, their comrades and successors from the communist Polish United Workers’ Party went to great lengths to set up a formally independent court to hold them accountable through an impeachment-type procedure—only to pardon them in July 1984, mere months after the trial had begun.

Before the Polish State Tribunal, public officials were liable for violations such as the non-fulfillment or improper performance of duties in executing their offices. In comparison to the US practice of impeachment, where the legislative branch exclusively levels charges and holds a vote on conviction, the socialist State Tribunal’s judges were not members of parliament. In the United States, the impeachment procedure is about removal. But in Poland, where, at the time, there was no irremovable elected post, the purpose was symbolically to convict an already-former official.

The 1984 State Tribunal trial was preceded by an amendment to the constitution and a complicated two-year parliamentary procedure. How was it even possible to introduce such an institution into state-socialist Poland? What led the communist leadership to limit their powers and establish a special court before which their actions might be sanctioned? The answer to this question is inseparable from the eventful history of the early 1980s in Poland, and also interrogates many stereotypes of how law and politics functioned the socialist Eastern Bloc.

Socialist Legality

When it came to constitutional law in Poland, the influence of the Soviet Union and the pressure to unify within the Eastern Bloc was in fact very minor. Instead, lawyers constituted an influential group within the elite. Without questioning the overall legitimacy of the communist party-state, members of the legal profession had, since the advent of de-Stalinization in 1956, advocated that the state’s power should be executed only through predictable legal rules. The term “socialist legality” (socjalistyczna praworządność) was coined and used as an ideology of cautious reform.

The adjective “socialist” might be misleading, since these legislative projects seldom included any particular socialist values. In fact, the legality in question was an authoritarian one, in which lawyers presented the communist party with formal procedures and institutions that served to stabilize its rule. As the true sovereign, however, the party had the right to make exceptions.

Solidarity

This program of legality in an authoritarian state-socialist regime faced various setbacks while also bringing about tangible effects — especially within administrative law, where citizens could appeal unfavorable official decisions. This top-down legalism encountered challenges in 1980 and 1981. A nationwide wave of workers’ strikes in the summer of 1980 and the authorities’ decision to negotiate led to the creation of Solidarity, a self-governed labor union that immediately attracted a large membership across geographic regions and social groups. For sixteen months between 1980 and 1981, the authorities were forced to bargain with Solidarity—a startling, even revolutionary, development by previous Eastern Bloc standards. The movement applied pressure to pass new union, election, and association laws, and an economic reform granting self-management.

What the country witnessed during this time was a confrontation of two understandings of legality. Established lawyers, reluctant to question political power, saw its essence in codes, procedures, and institutions, whereas Solidarity’s version of legality centered on granting new rights and empowering the people in relation to the state. In other words, whereas one side implemented an authoritarian Rechtsstaat, a law-based institutional system with limited political liberties, the other side envisioned a socialist bill of rights.

This latter understanding, fostered by Solidarity, was gaining traction among the main constituency of the Polish United Workers’ Party—its rank and file. In 1980, the party base suffered two serious blows to its confidence when the state of the economy and the scale of foreign debt were revealed, and the political elite was caught up in scandals involving corruption and abuse of office. Many rank-and-file members called for legal consequences against former leaders, but the measures taken by those leaders' successors fell short of public expectations. Independently from each other, Solidarity and the communist party base requested the creation of a special court, called either a National or a Citizens’ Tribunal, that would enact a socialist-style impeachment trial.

Responding to this public mood, constitutional lawyers advocated the establishment of a State Tribunal, which had already existed in Poland before the Second World War. However, the idea gained little traction initially, instead facing criticism in legal circles. For a time, the conundrum of reconciling popular and established understandings of legality remained unsolved.

The Trial

The situation took a dramatic turn on December 13, 1981, when Army General Wojciech Jaruzelski took power and ended the political conflict. Jaruzelski introduced martial law and incarcerated thirty-six former communist officials, including former heads of Party and government. The State Tribunal project was suddenly re-introduced, and its draft bill immediately legislated. This time, even behind closed doors, no one voiced serious objections to an idea that, only months before, had seemed unacceptable. Under the state of emergency, Jaruzelski continued the project of socialist legality, but with the State Tribunal he went a step further, promising to hold former leaders accountable in a constitutional fashion.

Neither the MPs nor their constituents in 1982 knew what the State Tribunal was supposed to do. One voter likened it the Nuremberg Tribunal where “certain people would be put on trial, hanged and the case closed.” Yet the outcome of the parliament’s work had little to do with such fantasies. Socialist lawyers were instead hard at work. There were no harsh punishments, and the procedure was complicated, time-consuming and required establishing criminal intent.

The parliamentary indictment claimed that members of the 1970s-era government had violated the Constitution and other laws by breaching the guidelines of economic plans and allowing national debt to accumulate excessively. The proceeding before the parliamentary committee tasked with verifying these charges was held behind closed doors, and was far from spectacular. There were a lot of laborious procedural deliberations, and the hearings of the indicted former officials, although extensive, were spent debating the scope and legitimacy of the tribunal.

The actual State Tribunal began its work only in March 1984, after motions from the defendants gave them extra time to analyze the evidence. Meanwhile, the authorities prepared yet another surprise: an amnesty law was passed, which closed all cases before the tribunal. The first-ever proceeding was thus cut short without any verdict.

The State Tribunal was rooted in the emerging tradition of socialist legality in communist Poland, which sought legal remedies to political problems. It came to life after a revolutionary period in 1980-81, when retribution against former leaders was seen as a chance for justice. As an experiment in socialist-style impeachment and an attempt to address public discontent with governance, the Tribunal was a failure. Ingrained institutional procedures precluded any hasty or spectacular action, causing its promoters to retreat. In the end, despite the authoritarian setting, it was legal constraints that stemmed a once-zealous political will.