The following is an abridged and reconceptualized version of the article “Tatars and Imperialist Wars: From the Tsar’s Servitors to the Red Warriors,” Ab Imperio 1 (2020): 164-96.

Norihiro Naganawa is Professor of Central Eurasian Studies at the Slavic and Eurasian Research Center, Hokkaido University, Japan, and currently a William D. Loughlin member of the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study.

Journalists and political commentators often depict home-grown radical Muslim youth as challengers to liberal Western democracy. Why do apparently integrated European citizens decide to violently resist a society where they are born and raised? Is jihad somehow "intrinsic" to Islam in a way that warrants this level of radicalization?

With observers consistently pointing to the social isolation and lack of opportunity Muslim youth often confront, why are European societies reluctant to listen to Muslim citizens who — speaking a shared language of liberalism — ask for equality combined with individual recognition of difference? These questions are very familiar to historians of Muslim regions in the Russian Empire, particularly the oldest and most integrated one within Russia’s body politic: the Volga-Urals region.

The Volga-Urals Muslims were not colonial subjects, having undergone all the transformations the rest of Russia endured since the middle of the sixteenth century, right alongside Orthodox Russians. If, as Alexander Morrison argues, Alexander II’s Great Reforms indeed introduced a divide between metropole and colony to a vast landmass empire in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Volga-Urals Muslims were firmly incorporated into the Russian people, enjoying the benefits of all participatory projects like courts, schools, and local self-governments, all while maintaining their distinction within the tsarist confessional administration.

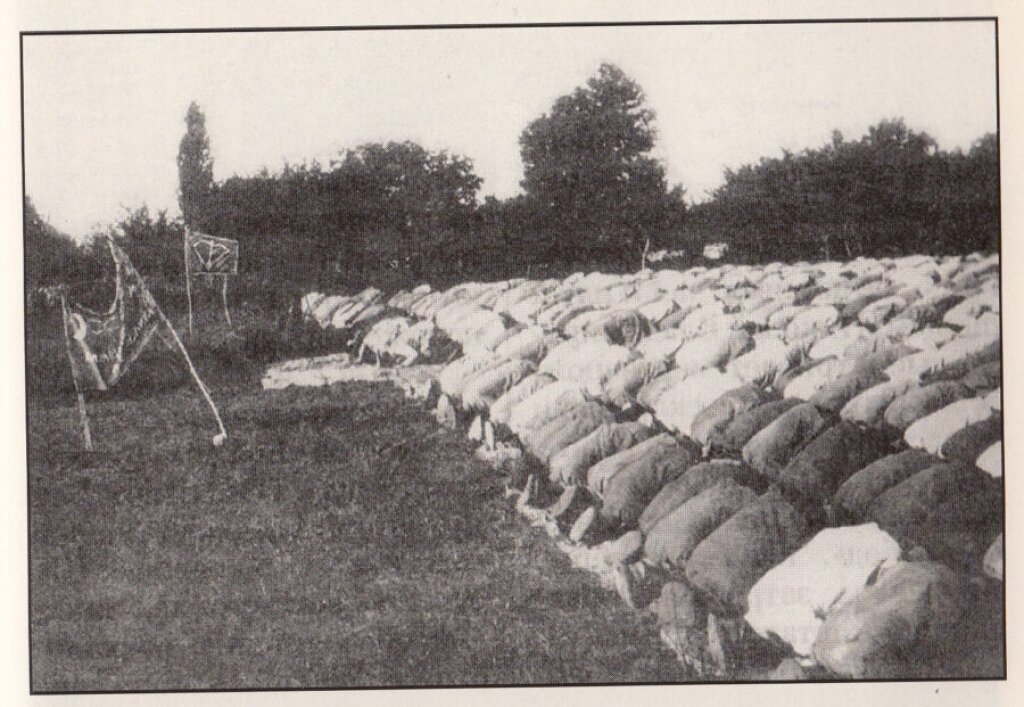

Rights accompany obligations. Unlike other co-religionists of the Romanov Empire, the Volga-Urals Muslims served in the tsar’s regular army since 1874 under universal conscription. By the end of the dynasty, they had experienced war with the Ottomans, Japanese, and Germans. Like other peoples, they were aware of other wars in an increasingly violent imperialist world. The First World War saw Russian Muslim soldiers ranging in number from 700-800 thousand to 1.5 million, a much larger proportion of the overall armed forces than among Muslims in Britain’s Indian Army or France’s African soldiers. Moreover, unlike colonial Muslim soldiers, who operated as separate units as they fought for Western Europe, the Volga-Urals Muslims were dispersed among and intermingled with a Russian Orthodox majority, other Christians, and Jews, then experiencing the immense pressure of Russification.

The army and wars were such major parts of the society of Volga-Urals Muslims that they notably shaped public conversation over citizenship, the "body and soul" of the nation, and its fates in an increasingly brutalized world. After the 1905 Revolution, a burgeoning Tatar-language press further catalyzed participation in international conflicts and the development of a vibrant Volga-Ural public sphere. As Ilham Khuri-Makdisi argues in her book on global radicalism in the eastern Mediterranean, print media enabled people to feel connected to the world, producing a population that considered itself entitled to interpret, draw lessons from, and thus participate in events taking place on a global scale. By reading about immediate local concerns and global events simultaneously, subjects universalized their own contexts and localized the global.

Indeed, the 1905 Revolution itself emerged out of the Russo-Japanese War. St. Petersburg was bombarded with massive petitions requesting equality with Russians and, in particular, collective rights for Muslims, whose men fought desperately far away from home, often leaving family members in distress. In these petitions, army-related claims occupied an important place: desiderata included the appointment of Muslim chaplains, the provision of a proper diet, and respect for Islamic rituals, as well as the release of parish mullahs from mobilization alongside Orthodox clergy.

Seeing the first Russian revolution waning, Muslim youth fascinated by socialism and anarchism continued to publish articles enthusing about constitutional upheavals in Iran and the Ottoman Empire, both of which occurred during a temporary ebb in Russian imperialism.

This revolutionary and emancipatory environment shaped Tatar narratives of Russia’s wars. Two war accounts emerged in Kazan in 1909: one relates to the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 to 1878 by one ‘Ain al-‘Ibad Hasan ughlı Hasanof, a former chaplain in the Anatolian front. The other treats the Russo-Japanese War and is by one ‘Abd al-Khaliq b. ‘Ain al-Din Ahmerof from the Orenburg Province, a former detainee in a POW camp in Osaka, Japan. These authors, as witnesses of the Russian army’s atrocities, expressed profound doubt and rage about the tsarist cause.

In contrast to the Russophone discourse of war with the Ottomans as a civilized affair complying with international law, and as an instance of Christian Slavic victory over Islamic Turks, Hasanof depicts Russian troops engaged in plunder, arson, shooting of evacuees, and slaughter of civilians — including small children. He prays for God to reward as martyrs (shähidlar) not only the Ottomans fighting against the infidel forces, but also fellow believers from the Volga-Urals region — a controversial claim in light of Islamic legal tradition. The specter of the apocalypse loomed large for Hasanov, who encountered clouds of locusts—one of God’s manifest signs according to the Quran—on his way back to Tbilisi.

Ahmerof, meanwhile, had participated in the decisive battle on the 203-Meter Hill during the siege of Port Arthur at the end of 1904. Denouncing the generals’ decision, which caused a huge number of casualties and prisoners, he declares: “Our generals did such injustice in this battle; it was impossible for anyone’s conscience to accept this fact.”

Ahmerov’s life as a prisoner in Osaka hints a moment of exposure to transnational radicalism for the Volga-Urals Muslims. The Osaka camp, which housed the largest concentration of Port Arthur POWs (including 650 Muslims), was a prime propaganda target for the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom, one of whose agents was peripatetic Narodnik Nikolai Sudzilovskii-Russel (1850-1930). Since the army forced the Muslims to learn Russian, they might have listened to radical agitation for illiterate Russian soldiers, digesting it at their own study circles. In doing so, Ahmerov could presumably contextualize the Russo-Japanese War within a chain of imperialist scrambles: the Russo-Turkish War, the Sino-Japanese War, and the Boxer Rebellion. Muslim soldiers would often bring these anti-imperialist ideas back home.

Another pivotal moment before 1914 that again revealed the inconsistency of "civilized" Europe within a cruel world order of competing nations were the Balkan Wars, which future Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky also observed as a Vienna correspondent of Kievskaia mysl’. With its editor Fatih Kärimi (1870-1937) reporting from Istanbul from November 1912 to March 1913, the Orenburg newspaper Waqt (Time) significantly shaped regional Muslim youth’s understanding of nation as an organism (with women’s status as a criterion of its health!), the struggle for survival between the Turks and the Christian nations, progress toward civilization, “humanitarian” Europe’s indifference toward Muslim victims in the Balkans, and the European powers’ encroachment upon Ottoman sovereignty. As Khuri-Makdisi and Houri Berberian argue about Syrian and Armenian radicals respectively, these historical elements should not just be read within a repertoire of nationalist speech, but as of a piece with global radical culture.

These simmering resentments and instances of intellectual work all came to a head in 1917, when radical Tatar youth began seeking solutions to their people’s sufferings in Bolshevism. Invoking rich images of wars that had appeared earlier in the Tatar press, Tatar political workers in the Red Army explained the necessity of supporting the Bolsheviks to their fellow soldiers, encouraging them to continue fighting even after an already four-year war.

When considering "radical Islam" today, it is thus crucial to recall how directly Muslim thinkers have historically linked domestic with international injustice, even as Western liberal democracy has treacherously and violently broken its own promises to minority peoples.