How do you build drama around an election with a foregone conclusion? An election that has barred the participation of the most viable opposition candidate (with “viable” as the operative word only when grading on a serious curve)?

In Russia’s case, the answer, apparently, is Ksenia Sobchak.

Rock On, Gold Dust Woman

Ksenia Sobchak has been in the public eye for most of the 21st century. As the daughter of the dead (and partially disgraced) democratic leader Anatoly Sobchak, as a student at the elite Moscow State Institute for International Relations (MGIMO) and notorious party girl, Ksenia put the gold in “golden youth.” While completing her senior thesis, she developed and hosted “Dom-2” (“House 2”), the hugely popular Russian version of the Big Brother reality franchise. The most common label for her in the Anglophone media is "the Russian Paris Hilton,” a lazy and offensive characterization even worse than the frequent appellation “socialite” (a word which, like “spinster” and “loose woman,” should surely have outlived its welcome by now).

After years on state television, Sobchak threw her lot in with the opposition Yes, she was dating an opposition figure at the time, but give her some credit—she’s far too smart and accomplished to be written off as a postmodern update to Chekhov’s “Darling,” changing her personality along with her men. In recent years, she has hosted a talk show on the independent TV-Rain channel, with guests from a wide range of the country’s political and cultural life, while remaining a fixture of Moscow’s glamour circuit (Rule of thumb: when she wants to be taken seriously, she puts on her retro-hip librarian’s glasses).

It’s tempting to treat Sobchak’s candidacy as a joke (seriously, it’s hugely tempting). But Ksenia Sobchak isn’t just a punch line. Her candidacy, like her entire career, is both serious and not entirely serious, both a joke and not entirely a joke. Or perhaps both at once: Schrodinger’s Cat is finally running for public office.

Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Beautiful

Russia could do a lot worse than Ksenia Sobchak. In fact, most countries currently are (not everyone gets to be Canada). Her time as an It Girl in the public spotlight proved her to be a carefully-managed brand, with Sobchak herself as a savvy entrepreneur and indefatigable multitasker. As a TV host and journalist, she comes off as well-spoken, patient, and intelligent. Sobchak is an excellent interviewer (except when she doesn’t want to be, as was the case with her disastrous Pussy Riot interview).

Sobchak has, at least for now, put to rest concerns about her role as a spoiler, pledging to step aside if Alexei Navalny is by some miracle allowed to run. No doubt, there is something gimmicky about such a celebrity candidate. Her filmography alone is a jarring contrast to politics as usual, with roles including Eva Braun and the Russian voice over for Mindy Kaling’s Disgust character in Pixar’s Inside Out. At 35, she has grown up in public, with no shortage of televised embarrassing moments. But in the age of Donald Trump, is this really an obstacle?

A glamour girl running for president is also vulnerable to accusations that she is trading on her fame and beauty, but the assumption that one can’t be both pretty and smart is one of the oldest sexist canards. And, again, we have Canada: a Sobchak presidency could be a fine precursor to a revived, progressive transnational monarchy. Just imagine the beautiful babies she would have if she were carefully mated with Justin Trudeau, like two endangered, globalist pandas. It’s as if the Hapsburgs had inbred for brains and looks rather than bulging eyes and feeble-mindedness.

I’m With Her?

So let’s try for a moment to take her candidacy seriously. She has no experience in government, but neither does Navalny. It’s also difficult to imagine how Sobchak could appeal to ordinary Russians, who might be put off by her glamour and her reputation. Not to mention her politics: in a country where “liberal” is practically a swear word, Sobchak’s brand of liberalism is all too familiar from the much-maligned 90s: a progressive set of social policies combined with Thatcherite economics.

There is, however, one issue on which Sobchak has long behaved like a canny politician: Crimea. Her initial tweets after the peninsula’s annexation were largely positive, and a recent TV-Rain split-screen video took footage of an earlier interview Sobchak had done with Navalny and combined it with other recordings of Sobchak, so that Sobchak seemed to be interviewing herself about her own candidacy. Journalist Sobchak (hair down, no glasses) asks, “So what’s the deal with Crimea? Are we supposed to give it back, or what?” The camera turns to Candidate Sobchak (hair tied back, glasses), who says nothing, to the accompaniment of chirping crickets.

The Crimea issue split Russia’s small liberal community, with Irina Prokhorova, for example, refusing to compromise her principles by accepting the annexation, preferring to leave her nascent political movement. But there are three truths we must recall about Crimea:

1) Russia should return Crimea to Ukraine, because Russia had no right to take it. (Technically, Crimea should probably be returned to the Crimean Tatars, but as a citizen of a country founded on forced resettlement and indigenous genocide, I see the walls of the glass house that encloses me. )

2) Russia is never going to return Crimea to Ukraine

3) No candidate could win the Russian presidency on a “let’s return Crimea" platform.

Crimea is the third rail of Russian politics; by steering clear of it, Sobchak retains a modicum of viability.

All She Wants to Do Is Dance

Realistically, Sobchak is not going to become president of Russia in 2018. Even she doesn’t seem to think so. In its early days, her candidacy has been marked by a kind of resigned nihilism. Her current slogan is that a vote for Sobchak is a vote against everybody. Besides her gender and the faint whiff of political dynasty, Sobchak has little in common with Hillary Clinton, but she does seem to be magnifying Clinton’s error in focusing on her opponent’s negatives rather than her own positives.

So far, Sobchak has done little to combat the most cynical interpretation of her candidacy: that she is running at Putin’s behest. She claims that she simply informed Putin, rather than asking permission, but she is not particularly persuasive. Indeed, her close ties to Putin have long haunted her in her role as an opposition figure. In a country often characterized as a mafia state, rumor has it that Putin is literally her godfather.

Is it a coincidence that, after years as persona non grata on state television, Sobchak is back? It looks like, when it comes to her career, her future and her brand, she is playing a very long game.. Remember how young she is (35!)—presumably, she will have numerous opportunities to reinvent herself in public before she is Putin’s age (if she isn’t mysteriously shot by unidentified assailants, as have so many politicians and journalists who have run afoul of the president and the security services). We can imagine what’s in it for Sobchak. But what’s in it for Putin?

With Sobchak, Putin preserves the pretense that this election is real. No doubt Putin wants a decisive victory; if he were more willing to let the results be close, Navalny would probably still be in the race. But he probably doesn’t want a Central Asia-style victory of 99% or more.

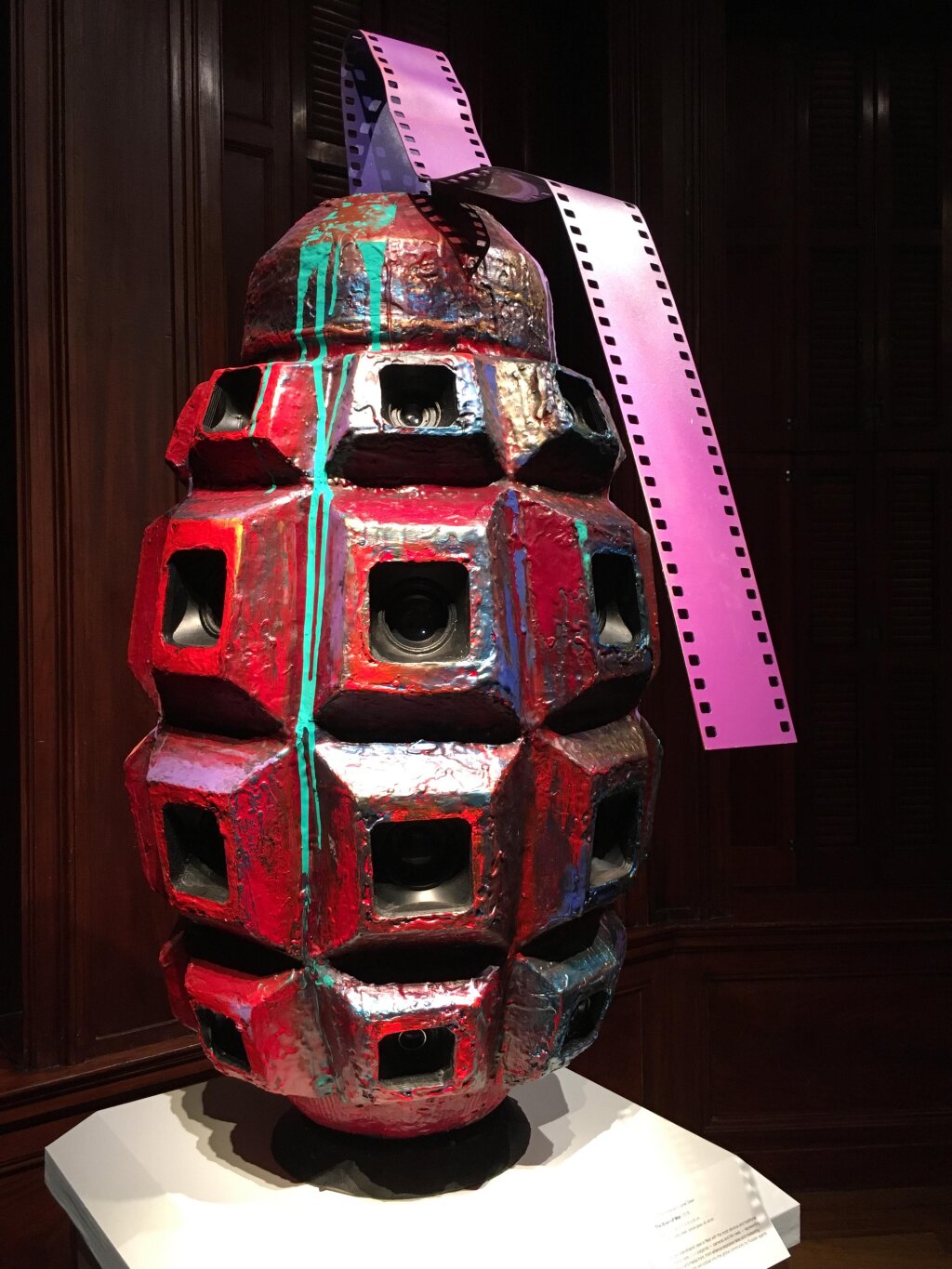

Before Sobchak, the election threatened to be terribly boring. Now it has an ex-reality star willing to leverage her talents and experience to simulate a democratic process. How perfect, then, that her breakout hit was the Russian version of Big Brother! Big Brother doesn’t just want to watch us; he wants us to watch him.

As long as we pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. Because clearly, he’s here to stay.